Montana habitat key in plans to protect wolverine, now listed as threatened

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

After nearly two decades of legal wrangling, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has issued a final ruling declaring the North American wolverine to be a threatened species. The wolverine’s new status as a threatened species makes their killing or harassment illegal. The new protections also require U.S. Fish and Wildlife to prepare a wolverine recovery plan, identify critical habitats for protection and look at the possibility of the reintroduction in certain areas.

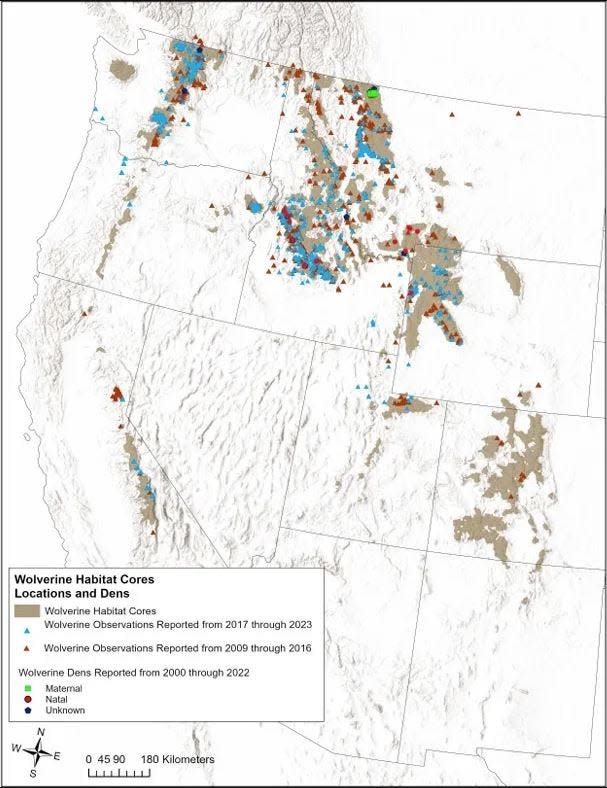

Montana is central to the wolverines’ recovery process, as one of three states in which the animal’s primary habitat is identified.

“Wolverines once ranged across the entire northernmost tier of the United States from Maine to Washington and southward down the spines of the major Western Mountain ranges as far as California and New Mexico,” the USFWS final report reads.” Today, wolverine populations exist in the lower-48 states only in the Northern Rocky Mountain regions of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, in the Cascade Mountains of Washington. Biologists estimate that, in total, the lower-48 wolverine population consists of no more than 300 individuals.”

Designation of the wolverine as a threatened species was opposed by members of Montana’s Republican Congressional delegation, including Montana Rep. Matt Rosendale. Rosendale’s objection to the inclusion of the wolverine is largely based upon a USFWS evaluation completed in in 2013.

“Basing this determination on climate modeling and projections that have been consistently inaccurate over decades does not meet the standard of ‘likely’ or even probable at this stage,” the 2013 report states. “I urgently request a delay in the decision-making process to allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of the current state of the wolverine population. We cannot afford to restrict the activities and recreation of citizens of Montana based on projections and models that may not materialize and do not meet the requirements listed in federal law.”

Rosendale’s response was supported by both Sen. Steve Daines and Rep. Ryan Zinke.

Wolverines were first petitioned to be listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1995. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed to list the wolverine as a threatened species in 2013. In 2020, after reevaluating the wolverine’s status, the Service determined listing the wolverine was not warranted. In 2022, the District Court of Montana vacated that decision, meaning the wolverine was again considered a species proposed for listing under the Endangered Species Act.

“Wolverines are adapted to live in high-latitude ecosystems characterized by deep snow and cold temperatures,” the current USFWS report states. “Wolverines once ranged across the entire northernmost tier of the United States from Maine to Washington and southward down the spines of the major Western Mountain ranges as far as California and New Mexico. Today, wolverine populations exist in the lower-48 states only in the Northern Rocky Mountain regions of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, in the Cascade Mountains of Washington. Biologists estimate that, in total, the lower-48 wolverine population consists of no more than 300 individuals.”

The new protections require U.S. Fish and Wildlife to prepare a wolverine recovery plan, identify critical habitats for protection and look at the possibility of the reintroduction in certain areas.

“Current and increasing impacts of climate change and associated habitat degradation and fragmentation are imperiling the North American wolverine,” said Pacific Regional Director Hugh Morrison. “Based on the best available science, this listing determination will help to stem the long-term impact and enhance the viability of wolverines in the contiguous United States.”

Conservation advocacy groups have pushed for a federal wolverine listing for decades, and the species’ classification has been the subject of repeated litigation. States including Montana have opposed classifying the wolverine under the Endangered Species Act in the past, though the scarce creature's whereabouts in designated wilderness and other highly protected lands suggests a listing would have a limited effect on federal land management.

Research found the wolverine population in a 5,400-square-mile swath of the southern Canadian Rockies declined roughly 40% from 2011 to 2020.

This article originally appeared on Great Falls Tribune: Montana habitat key in plans to protect wolverine