Montclair Kimberley Academy event tackles societal movements as part of history series

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

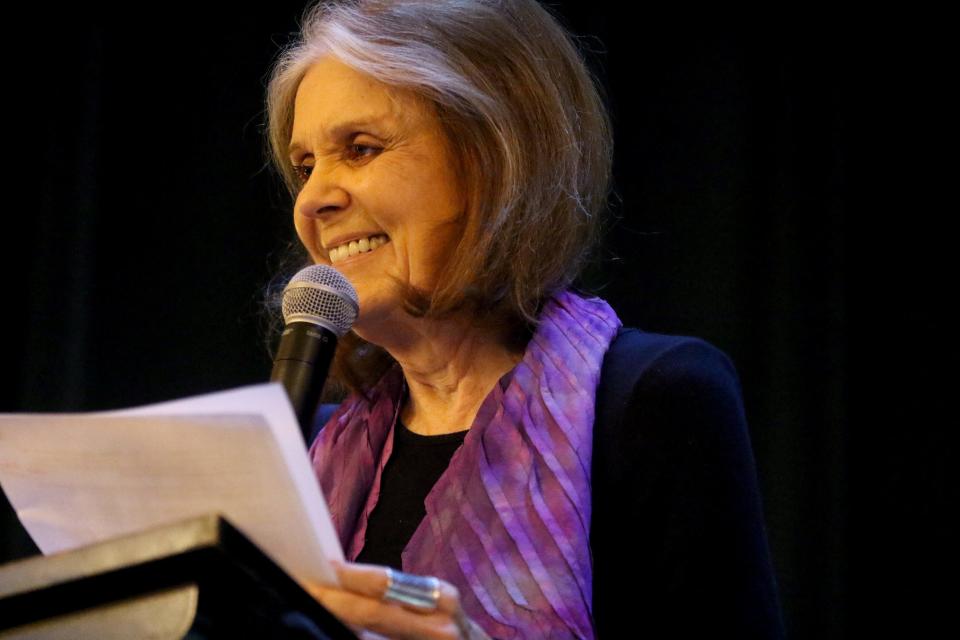

MONTCLAIR ― Salamishah Tillet, an activist and author, befriended second-wave feminist icon Gloria Steinem in the same way many academics forge their relationships, by calling her hero's rhetoric into question.

In 2008, when Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama were headed toward a Democratic primary that gave voters two historic options for U.S. president ― "I miss the days when we used to argue about those two," Tillet joked ― Steinem was engaged in a friendly match of wits with Black advocate and broadcaster Melissa Harris Perry.

"In that conversation it felt like you had to choose Hillary or you had to choose Obama, and you had to choose race or you had to choose gender," Tillet said, recounting the story during a recent moderated talk with Steinem at Montclair Kimberley Academy's Upper School.

But Tillet rejected the false binary and penned a blog post wielding her pen as a sword aimed directly at the two thinkers: "I critiqued Melissa; I critiqued Gloria. Somehow the blog got sent to you and you responded to me," she said to Steinem. "That’s how we met."

In one her many clever rejoinders of the evening, Steinem, 89, said, "The problem is I don’t remember the story. Now I love her," referring to Tillet. She gave her cohort's hand a tender pat.

But bringing the anecdote back to its true meaning, Tillet said Steinem's reaction "speaks to how she engages debate and criticism."

Ever since, the two have remained friends and equals, open to debating treacherous issues that often feed the archetype of liberals and their self-described social media pundits as splintered, if not unproductively didactic.

Last week, they continued their debates with interruptions of agreements, or vice versa, before a packed house at MKA, as part of the school's Hemmeter History Lecture series.

Essex County NJ Essex County voters mostly stay home as reshaped districts elect new Democratic leaders

With the school's history teacher, David Hessler, serving as moderator, the friends proved that diverging opinions with a side of camaraderie are the core of any social movement's efficacy.

As Tillet — a critic at large for The New York Times and a professor of African American studies and creative writing at Rutgers — phrased it: "So much of being feminist is what you do in private … how you treat people when no one else is looking."

Defining feminism

Over the past few years, a battle has raged within the scrolling op-ed page of social media between "dyed in the wool" Democrats and a burgeoning far-left movement concerned with the power of language and faulting its less militant counterparts for falling behind in the culture war by clinging to a less inclusive or historically problematic diction.

But the arguments are hardly new. In the 1960s and '70s, Steinem rose to the forefront of the second-wave feminist movement, which placed its focus on women's place in work and politics ― shattering the so-called "glass ceiling," backing the Equal Rights Amendment and fighting pervasive sexism.

That all seemed like a valiant fight. But Black feminists who approached the feminist battleground with viewpoints engendered by the concurrent Black Power movement are often recalled as having rebuked the feminist uprising as overtly concerned with the trials of their white, middle-class counterparts, overlooking the unique hardships of women of color.

However, Steinem and Tillet said that was far from the truth. They cited a groundswell of support from Black women for the second-wave movement.

Nevertheless, some Black advocates created what they saw as the more inclusive label, "womanist," which both Steinem and Tillet credited to Alice Walker, author of "The Color Purple."

"She really loves the lush word of 'womanist,'" Tillet said of Walker. "It was very Southern." But while acknowledging the term's inherent strength, Tillet said she describes herself as a "Black feminist," in an effort to evoke a more inclusive nomenclature that acknowledges the intersectionality of race and gender identity amid historical patriarchy.

"Racial justice is part of how I define feminist," she said. "When we think of '-isms,' the impressions that we’re trying to challenge ― like racist or sexist — 'feminist' kind of sounds like a negative term even though it's liberative. So there’s something about that '-ist' part that kind of makes it seem not as open as we want people to experience it."

Steinem also questioned whether the root of the word "feminist" created confusion or gatekeeping as to who could take on the label.

"The feminine part sounds lesser than, or weaker than," Steinem said. "So Alice Walker’s objection to it made sense. To say 'womanist' sounds stronger. However, for a guy to say he’s womanist is problematic."

But getting into the weeds with regard to word choice can cloud recognition of one's actions, she added.

"We don’t get to choose what word we want," Steinem said. "It’s important that we think of the most supportive, compassionate thing we can do — and do it regardless of whether it’s the right language or the wrong language."

"It would be a waste of resources, opportunity, and it would be ineffective for equality" if certain groups were shut out of a movement due to vernacular, Tillet said. "We’re bringing more people into the category rather than shoving people out."

As a current example, Tillet cited Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, which were both founded by Black women and are not, as Tillet said, "competing movements.”

"If we don’t think about feminism in a way that is trying to achieve racial justice, if it’s not about trans rights, if it’s not about equality for everyone, then it’s not effective," she said.

Believing in choice

Hessler asked both women their thoughts on the previous night's election, which saw voters in multiple states turning out in a majority to protect abortion in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court's June 2022 decision to overturn Roe v. Wade and with it a longstanding federal right to the procedure.

Nov. 7 results in states like Ohio, where voters enshrined a right to abortion, and Kentucky and Virginia, where blue waves rejected Republican candidates who ran on anti-abortion platforms, were both literal and figurative referendums on the issue, according to a report from USA Today.

"It’s only proving what we all knew before," Tillet said, referring to prior polls by Gallup and Pew Research showing that a majority of Americans believe abortion should be legal under certain circumstances and within certain trimesters, as well as a majority objection to the Supreme Court's 6-3 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, which ruled that abortion was not a constitutional right and returned regulation of the procedure to state governments.

"People say it wasn’t part of the constitution. Yeah, well, women weren’t part of the constitution, either," Steinem said in a swift rebuttal to the central conceit of the Dobbs opinion.

"What these elections are showing us is when you have a democratic process ― as opposed to a few people making a decision for many ― choice is what people believe in," Tillet added.

'What kids see'

Both credited their work to their parents, with Tillet, who was born in Boston's Black enclave of Dorchester in the 1970s, saying that although her parents were not radicals in the vein of the Black Panther Party, they were involved in the Black Power movement and would now be described as "cultural nationalist[s]."

"We grew up with a consciousness around race," she added, "and that the arts can be a form of liberation, escape and resistance."

In her middle school years, Tillet said, she lived in her father's native country of Trinidad and returned to the U.S. to attend high school in Livingston, where she was one of only four Black students.

It was only then that she developed a consciousness around her race: "While racism was there [in my earlier years], I wasn’t interacting with the everyday racism that I experienced in high school."

What's more, Tillet graduated in 1992, the same year Anita Hill testified before Congress about her alleged sexual harassment at the hands of soon-to-be Justice Clarence Thomas and the Los Angeles uprising that followed the infamous Rodney King verdict.

"It’s so important what kids see," Steinem noted later.

But spending her formative years in Black communities forced Tillet to recognize how her gender set her apart from others, and even created certain expectations, if not limitations.

"My gender consciousness preceded my racial consciousness," she said. "I was aware I was treated differently because I was a girl."

Steinem described her parents as New Deal Democrats who "loved the Roosevelts" and lived through the Great Depression. "They gave me a sense that daily life was connected to politics," she said, nearly echoing the feminist rallying cry that "the personal is political."

In need of a summer job during high school in Washington, D.C., Steinem said, she applied to work at one of the city's public pools. Rather than work at a pool in the district's predominantly white Georgetown neighborhood, she was assigned a position in the city's southeast.

"It was a helpful experience to be the only white person," Steinem said of working in a Black community as a teenager. "I could feel them waiting until I got over being self-conscious."

But what sealed her fate as an activist was a trip to India amid Mahatma Gandhi's non-violent efforts to win his country's independence from British rule.

It was not only a powerful entree into resistance, but taught the young Steinem that knowledge of cultures beyond her own would be necessary for fighting oncoming battles at home.

"I began to realize how limited our [historical lens] was," she said of befriending activists beset by an oppressive force foreign to herself, even those in her own country. For example, working alongside indigenous Americans taught Steinem "to think about [history] when human beings started and not just when Columbus showed up."

Yet Tillet and Steinem said they are now learning as much from the future has they had learned from the past.

Recent movements led by younger generations have highlighted oversights endemic to both activists' prior perspectives.

"We’re indebted to them for Black Lives Matter. We’re indebted to them for getting us beyond a gender binary. Even as they’re constantly being attacked," Tillet said of millennials and Gen Z.

"The right, or ultra-conservatives, they’re actually using an intersectional lens," Tillet continued. "If you look at Texas, it’s not just transgender rights that they’re curtailing. It’s voting rights. It’s reproductive rights.

"We need to be as sophisticated in our analysis as the attacks are," she said.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Montclair NJ event tackles societal movements for history series