How a Montgomery charter school wound up in a $1.9 million food fight

Editor's note: Additionally, this story has been updated to clarify that while the Alabama Charter School Commission denied LEAD’s application to accept new students for ninth grade next year, current eighth graders may attend ninth grade at LEAD.

Struggling Montgomery charter school LEAD Academy owes the government nearly $2 million it says it doesn't have. It's waiting on the state's highest court to decide whether to uphold a ruling that Crave Cafeteria Services — not the school — is on the hook for the money.

And it all started with school lunches.

LEAD officials say Crave Cafeteria Services — run by a pastor with a fraud conviction who has been sued several times in the past few years for allegedly failing to pay for goods and services provided to his church and companies — inflated the number of meals it served while under contract as LEAD's food service management company.

Brian Pleasant, the man who runs Crave, says he wasn't responsible for the paperwork that got the school into this mess.

The government gave the school five years to pay back the money, which the school has already paid to Crave.

Was it a simple case of inexperience, a lack of oversight and poor record-keeping? Or was it a case of fraud, as LEAD alleges in its lawsuit against Pleasant and Crave?

First, an overview.

For subscribers: Who's the Alabama man fighting to keep $1.9M in lunch money dispute?

Audit shows insufficient records behind claims for reimbursement

AL.com reported on March 17 that LEAD Academy, a Montgomery charter school in its fourth year of operation, owed the federal government $1.87 million for overclaimed school meals.

Under the federal school lunch program, each time a school gives a student a meal, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reimburses the school a certain amount of money. If an outside contractor handles the school’s food service, the school claims the federal money, reimbursing the FSMC, as was the case at LEAD.

Crave Cafeteria Services, run by serial entrepreneur and iCrave Fellowship Church pastor Brian Pleasant, was the school’s food service management company during the period that ALSDE reviewed. Pleasant’s contract with LEAD ended after the 2022 summer semester, LEAD Executive Director Erik Estill said.

But after much of that USDA money was paid to Pleasant's company, an Alabama State Board of Education (ALSDE) audit in early 2022 said a reimbursement for more than 600,000 meals LEAD claimed from August 2020 to January 2022 would have to be returned, according to a copy of the audit shared with the Montgomery Advertiser.

The state could verify fewer than 300,000 claimed meals that were eligible for reimbursement during that time.

Thousands of meals were claimed on days that weren't approved by the state, making them ineligible for reimbursement. Thousands of others were claimed at sites the state never approved.

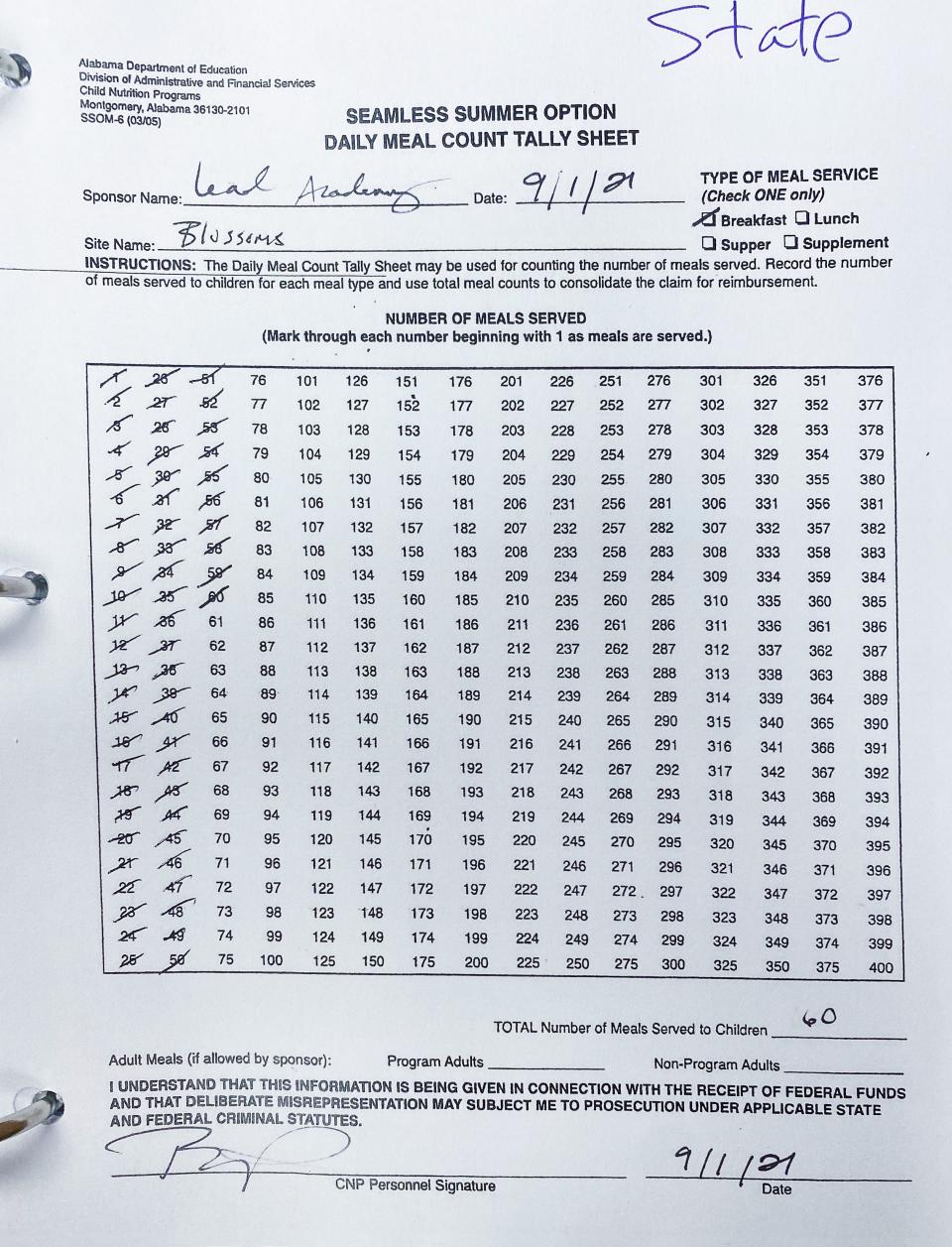

The tally sheets used to document the number of meals served were often incomplete and didn't match how many meals were claimed for reimbursement, the audit found.

The audit was performed after an anonymous tipster told the USDA that someone had inflated the number of meals that were served to children, according to LEAD officials and AL.com. Estill and LEAD President Charlotte Meadows say the tip came from a Crave employee.

LEAD sued Pleasant, Crave Cafeteria Services and Crave Café in November 2022 for $1.98 million — the amount owed to the USDA, plus interest — for breach of contract, fraud and unjust enrichment.

Pleasant isn't taking the blame. He says schools are responsible for counting and claiming meals under federal rules. While that’s true most times, the lines are blurrier in this case.

Regardless, Pleasant never filed a response in court, and Montgomery Circuit Judge Johnny Hardwick on Jan. 31, 2023, issued a default judgment ordering Pleasant, individually, to pay back the full amount to LEAD.

Pleasant says he was never served with LEAD’s lawsuit. Returns of service show the lawsuit was delivered to the same person for all three defendants: Crave Cafeteria Services and Crave Cafe. The returns of service list that person as an agent at Crave Cafeteria Services and Crave Cafe and Pleasant’s brother.

Pleasant has appealed the case to the Alabama Supreme Court, where as of late March he was representing himself, according to Alabama Supreme Court Clerk’s Office Staff Attorney Leale McCall. Although he missed an early March filing deadline to show why his corporation should be able to practice law pro se, McCall said the case is still before the court.

But back to the main issue: How did the school get into this mess?

Meal numbers got complicated when pandemic sent kids home

Days before LEAD’s first day of classes in 2019, the school was scrambling to find a way to feed its students. The Alabama Board of Education had to step in to force Montgomery Public Schools to provide food to the academy.

Meadows said in an interview that MPS was charging LEAD a price that officials felt was too high, and LEAD started looking for new options for food services in the second half of the school year. Rather than handle food service in-house, LEAD sought bids from food service management companies in March 2020.

Pleasant’s Crave Cafeteria Services was the sole bidder.

Crave was hired as LEAD’s food vendor beginning in August 2020. At that time, about half of LEAD’s roughly 450 students were attending class virtually because of the ongoing COVID pandemic, says Meadows, LEAD’s president.

Estill stepped in as LEAD’s executive director about a month later.

Virtual classes meant Crave had to prepare and deliver meals to students at school and at community drop-off sites. For the 2020-2021 school year, LEAD got approval from the state for Crave to deliver meals at several community sites each day. The next year, off-site meal deliveries were limited to one day a week.

As schools were stretched to feed hungry kids at home, federal waivers instructed schools and their food vendors to give food to any child aged 2-18 that showed up at a drop-off site, regardless of whether they attended school in that system.

Pleasant says that’s what he did. He submitted claims to the school of as many as 70,000 total meals per month; the school, in turn, submitted those numbers to the ALSDE, Meadows said. The ALSDE collected money from the USDA and forwarded it to LEAD. The school then sent “most of that money” to Crave, Estill said.

Money in hand, Crave could then pay business expenses, including vendors that provided food and supplies to Crave.

But LEAD claimed in its lawsuit that it picked up the bill for some of the vendors Crave failed to pay. Borden Dairy sued Crave and Pleasant for failure to pay, and a judge issued a default judgment in Borden’s favor in late March. That’ll be covered more later.

For now, back to Crave’s meal claims. Pleasant said he arrived at the number of meals he claimed for reimbursement by dividing the amount of food he purchased from vendors by the portion size included in each meal. That final number, he said, should amount to about the total number of meals purchased and prepared.

Crave was only supposed to be reimbursed for meals served. And it’s possible all those meals were served to children. But that’s not what the school thinks happened.

“It really comes down to however many meals you serve, that’s how you get reimbursed. And that’s why (Pleasant) inflated those off-site meals,” Estill alleged. “The higher his numbers, the more he was getting reimbursed.”

Who was supposed to be counting, anyway?

Typically, schools are responsible for counting and claiming meals served. But the federal government does allow for food service management companies to oversee counting and claiming, so long as that is specified in the contract between the school and FSMC.

In LEAD’s complaint, the school says that Crave and Pleasant “were allowed to complete documentation for meal counting and claiming” — not that they had to. The contract between the two parties left some gray area.

Here’s what the contract as it was filed in the school's lawsuit says: “The FSMC shall provide the following services: … The maintenance of all records as needed by the (School Food Authority) to support its claim for reimbursement; at a minimum, the FSMC shall report claim-related data to the SFA, promptly at the end of each month.”

It doesn’t specify exactly which records need to be maintained.

Pleasant believes that means he had to submit production reports, which is what LEAD based its reimbursement claims to the state on. When the state did its audit, it said it needed tally sheets to verify those claims.

For August to November 2020, the school had no tally sheets. All the money for those meals has to be returned, the state school board says.

From December 2020 to January 2022, the school was able to provide rosters documenting which students attending in-person ate school-provided meals. These rosters were completed by teachers, Estill said, and documents from ALSDE show that the state generally found those counts were accurate. Nearly half of the meals that the state was able to verify in its audit came from those served in LEAD Academy.

But ALSDE said that many of the tally sheets submitted for off-site locations didn't match how many meals were being claimed there. Many of those sheets were for days unapproved by the state, and many of them were also incomplete.

While he says he wasn't responsible for completing those tally sheets at off-site locations, he acknowledged that people on Crave's payroll filled them out.

Estill sent the Advertiser multiple photos of tally sheets that he said were signed by Crave employees, including some that appear to be Pleasant's name. Pleasant denies that it's his signatures on those sheets. Other examples of Pleasant's signature — including on his driver's license and documents filed in court — don't match those on the tally sheets.

Estill knows the signatures don't match — but he says they still came from Crave.

"Every one of those came from his people, and was signed by him or his people. We didn't sign a single one, so he can say what he wants but every single one of those sheets was signed by someone in his office," Estill said. "I don't trust a word Brian Pleasant says."

Estill said the school did not have CNP employees who could sign tally sheets at off-site locations, as those employees worked on site at the school.

“We kept rosters for the teachers to sign, which is why the findings are primarily for (Pleasant’s) off-site meal pick-up locations, not for our students eating at LEAD,” Estill said.

Meal delivery schedule changed in 2022, but nobody knew

In Crave's second year, the meal delivery schedule for off-site locations changed. LEAD submitted its state application with a new schedule where meals for the entire week would be delivered at those locations one day a week.

Pleasant says he didn't know about the change. And neither did Estill, until it was too late.

In an interview, Estill said he doesn't know who changed the school's application or what reason they had for doing so.

Crave continued delivering meals on those days that were approved the year before, Pleasant said, because he didn't know there was a change. Additionally, if someone from the school had been monitoring his work, as federal rules dictate, the error might have been caught.

Pleasant said it was the school’s responsibility to make sure all delivery dates were approved in the state’s application.

"I will call it what I call a novice mistake," on LEAD's part, Pleasant said.

No matter who keeps count, schools ultimately submit reimbursement claims

While the two parties disagree over was responsible for maintaining accurate documentation, LEAD submitted Crave's claimed meals for reimbursement from the state. And according to the ALSDE, even if food vendors document meals served, the school has to ensure they have the necessary documents.

“Take note that the food service management company is allowed to document the meals served, however, the school food authority must be able to provide these documents when upon request to support the claim that they submit to the state agencies for reimbursement,” ALSDE Child Nutrition Programs Director Angelica Lowe wrote in an email to the Advertiser.

In other words, LEAD was supposed to double check tally sheets against the meals Crave claimed it provided. In this case, they didn’t.

Estill said in an interview that the school accepts some culpability for the situation since it failed to make sure someone — either at Crave or the school — had complete, accurate documentation to prove those meal claims for reimbursement. Both Estill and Pleasant said they believed the employee at LEAD that oversaw the Child Nutrition Program was inexperienced.

Estill said the school has taken steps to make sure it is accurately overseeing its school meal program.

“Our CNP program, processes and oversight were changed, personnel were hired, and we make sure all numbers are double checked before we agree to anything,” Estill said.

State finds other issues with Crave's food distribution, reimbursement rate

The state found several other issues during its review beyond inaccurate meal counts:

From July 2021 to January 2022, Crave charged the school 12 cents over the approved lunch rate and 8 cents over the approved breakfast rate, for a total of $40,121 overpaid to Crave.

From October 2021 to January 2022, Crave charged the school $18,664 in payroll, which was not approved in the school's contract, the audit says.

During a review of one site, auditors found that Crave was providing meals that were not reimbursable. On Feb. 17, for example, Crave delivered a gallon of whole milk to Blossom Childcare and Learning Center, which makes only 16 servings of milk, according to LEAD’s review of the state audit. However, whole milk is not approved for the age group of children being served, which means all meals delivered were not reimbursable. Additionally, 30 sandwiches were delivered, but 40 vegetable servings were delivered.

Again, federal rules indicate that LEAD should have been monitoring what Crave was serving. The USDA’s guidance for school food authorities state that “the SFA must monitor the operation of the FSMC. Contract administration of a FMSC contract is more than just a periodic on-site visit in order to ensure that the FSMC complies with the contract and any other applicable Federal, State, and local rules and regulations.”

LEAD says it paid two of Crave's overdue vendor invoices

LEAD claims in its complaint that it had to pay invoices from Sysco and Merchant’s Food Service that totaled tens of thousands of dollars that Crave was supposed to pay. LEAD said in the complaint that Crave ignored collections requests from the companies.

One company also sued Pleasant for nonpayment related to his work as LEAD’s FSMC. Borden Dairy sued Crave and Pleasant for overdue payments in June 2022. Pleasant failed to respond and, in a default judgment issued in mid-March, Montgomery Circuit Judge J.R. Gaines ordered him to pay Borden $38,042, the total amount claimed, plus interest.

Pleasant alleged that the charges from Borden were in error and related to when Montgomery Public Schools was providing food to LEAD Academy a year prior, in which case he would not be responsible for the payments.

School officials never reviewed a background check on Pleasant

Pleasant has at least two criminal convictions, including one for federal bank fraud in 2007. The other is a 2015 conviction in Montgomery County for theft of property relating to his previous employment at the America's Best eyeglasses store on Ann Street.

Meadows told the Advertiser she wasn’t aware of Pleasant’s criminal convictions until the Advertiser mentioned them during an interview in March 2023. Estill said LEAD asks contractors about their criminal history only for the prior three years when they are applying.

Beyond that, neither Estill nor Meadows could confirm if the school performed a background on Pleasant before his contract was signed. Estill said it's possible the results went to Montgomery Public Schools instead of LEAD because of a misunderstanding between LEAD and the company performing background checks at that time.

“When Pleasant was hired our BG checks were being sent to MPS because company thought we were one of their schools since we were a public school in Montgomery,” Estill wrote in a text. While LEAD is public, as a charter school it is not part of Montgomery Public Schools.

The school has changed how it performs background checks to make sure that all employees and contractors are cleared, Estill said. “That has been corrected and now all contract workers are cleared and communicated to us before working for LEAD regardless of their role.”

LEAD Academy’s rocky history

LEAD Academy has faced litigation and controversy since before it opened its doors. The school applied to be Montgomery’s first charter school in 2017, and the Alabama Charter School Commission approved its application in early 2018.

However, a lawsuit brought by the Alabama Education Association against LEAD kept the school from opening in 2018. After the Supreme Court overturned a circuit court ruling in the AEA's favor, LEAD Academy opened in fall 2019, teaching about 350 students in grades K-5, with a plan to add an additional grade each following year.

During its first calendar year of operation, LEAD dismissed its first two principals, and the school was sued by its its first principal Nicole Ivey. After she was officially voted out of her position in October 2019, Ivey brought nine counts against several members of the LEAD Academy Board of Directors and other school officials in a 40-page complaint.

The school’s board responded in a statement in November 2019, writing in part that Ivey provided “false and misleading information” to try and salvage her reputation. Ivey and the defendants reached an undisclosed settlement, and Ivey released all claims against the defendants as the case was dismissed in March 2020.

Most recently, the Alabama Charter School Commission unanimously denied LEAD’s application to accept new students for ninth grade next year. Current eighth graders, however, may attend ninth grade at LEAD. Paul Morin, a member of the commission, complained that the school was “failing” and that leadership at the school was an issue. Morin declined a request for an interview for this story.

The issues with the school extended into the classroom. LEAD has consistently performed lower on testing compared to surrounding Montgomery schools. In 2021, the School Quality Report found that only 38% of classrooms were engaged in effective participation and engagement. That report also found that “the school does not yet have a clear process for identifying students who are struggling and at risk nor systematically monitors student progress.”

Notably, ALSDE's audit is also not the first time that LEAD has received claims for overdue payment. In February 2020, the Advertiser reported that Unity School Services alleged that LEAD failed to pay more than $76,000 for services provided as the school’s education service provider. Unity had stopped providing services in January after months of missed payments, Unity’s owner said.

What happens now?

Estill said the school is currently in talks with the ALSDE on how it will repay the money. LEAD doesn’t have the nearly $2 million it owes on hand, Meadows said, because it gave that money to Crave.

Estill said the school plans to pay ALSDE in chunks over the next five years, the time he said ALSDE gave LEAD to have the amount paid in full. ALSDE would not speak about the specifics of LEAD’s case for this story.

Attorney William Webster, representing LEAD, said in an interview in late March that he was planning to file a motion to dismiss with the Alabama Supreme Court regarding Pleasant's failure to meet the court's filing deadline.

Webster said if the court dismisses Pleasant's case or upholds the ruling for LEAD, the court must then determine how LEAD will recoup the money from Crave that the school owes the government.

Estill and Meadows are not confident that they will be able to get the full amount they say Crave owes them if that happens. And if the Alabama Supreme Court overturns the lower court’s default judgment against Crave, Meadows said the school will continue to fight it.

But that money is still due in five years, which Estill said may limit what the school may have been able to do with that money.

“It will limit, maybe, additional things that we may have been able to add for our students, which is frustrating,” Estill said. “It’ll be tight, but we’ll be able to manage.”

Evan Mealins is the justice reporter for the Montgomery Advertiser. Contact him at emealins@gannett.com or follow him on Twitter @EvanMealins.

Your subscription makes our journalism possible. Subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Montgomery Advertiser: How an Alabama charter school wound up with nearly $2 million bill