'Monumental figure': Art McNally set to become first official in Pro Football Hall of Fame

Art McNally never played a down in the National Football League.

He never coached someone in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, or anyone for that matter. He was never the architect of great football dynasties as a general manager.

Unfamiliar to the casual NFL fan, McNally was always considered a league innovator.

"He is a visionary when it came to officiating," Hall of Fame executive Bill Polian said.

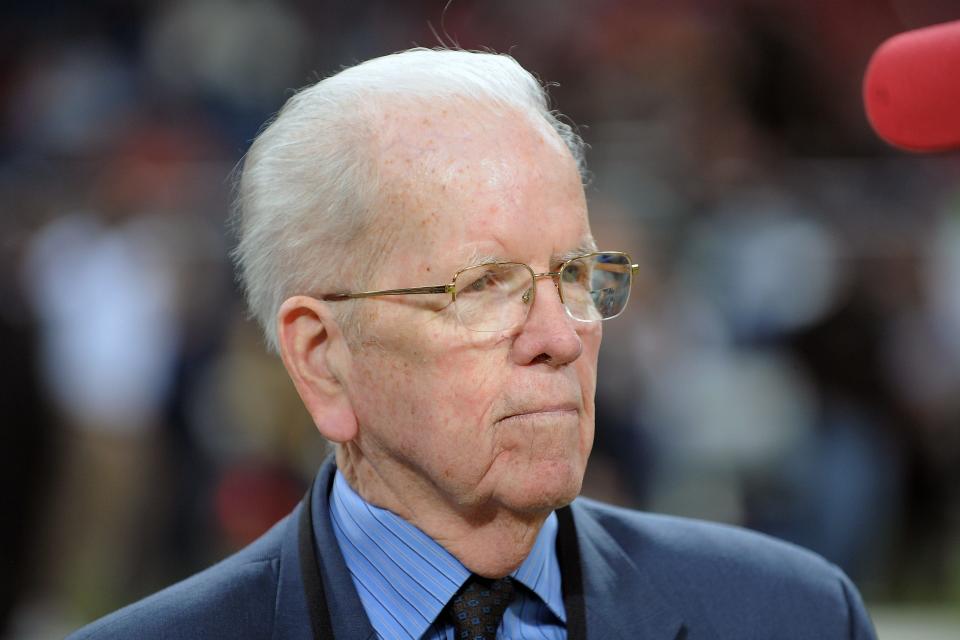

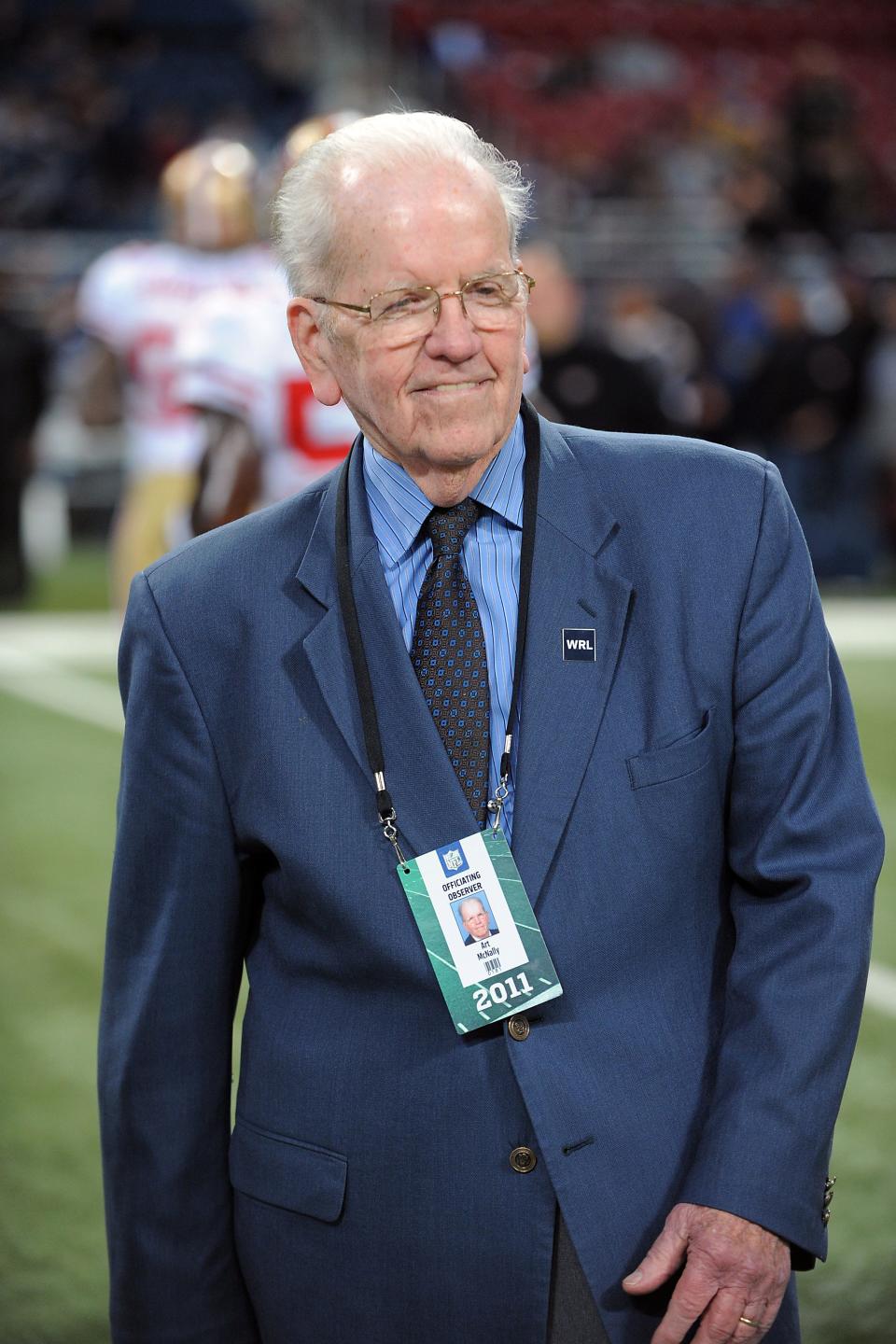

At age 97, McNally will become the first NFL official enshrined into the Hall of Fame. He worked as a field judge and referee in the league from 1959-67.

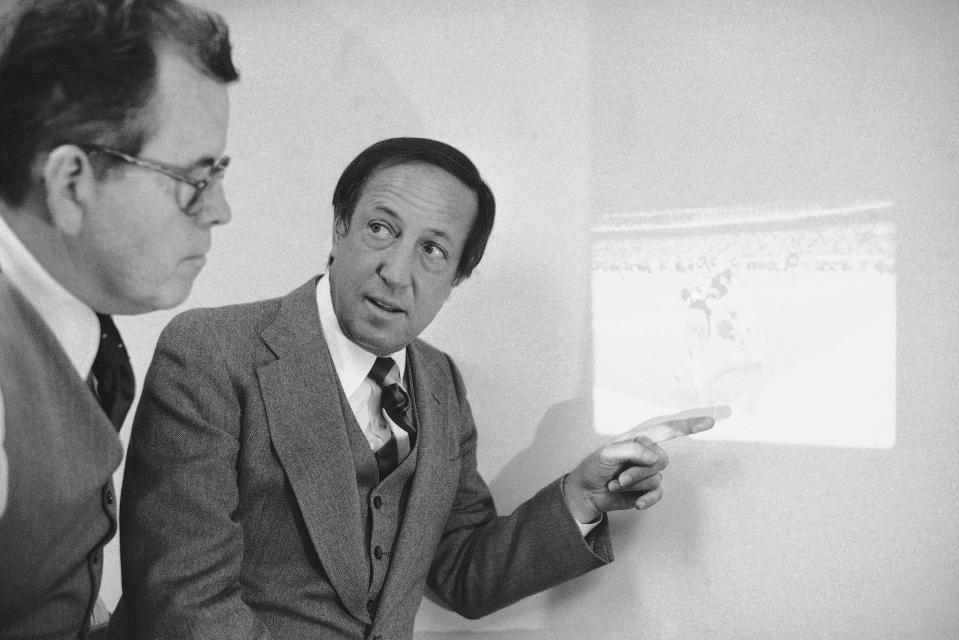

McNally cemented his Hall of Fame credentials from 1968-91 as NFL supervisor of officials. He developed standards for scouting, screening and hiring his officials. He introduced the first formal film study program for training officials. He modernized their grading system. He also oversaw the NFL’s first use of instant replay.

"He's the father of modern officiating," Polian said.

McNally grew up in Philadelphia. He went to Roman Catholic High School and attended Temple University. He served with the United States Martine Corps in World War II and taught high school in Philadelphia.

While he was a teacher, McNally spent this entire weekend officiating games. He worked a high school game on Fridays, a college game on Saturdays and an NFL game on Sundays. He officiated more than 3,000 football, basketball and baseball games during a 22-year period.

McNally embraced being an official.

"One year I worked 270 games, and after that I decided to cut back," McNally said in a 1990 interview. "But the next year I did 276."

Whether it was on a sandlot field or in an NFL stadium, McNally treated each game equally. He knew he could not always be right. However, he always tried to be honest.

"I gave it my best shot every time out," McNally said.

As NFL supervisor of officials, McNally led a five-man department who coordinated and directed a staff of game crews. He scouted, screened, hired and graded each official.

"He set up a system of scouting, training and evaluating officials that is the gold standard for every officiating group in every other sport," Polian said.

McNally held his officials to high standards. He never wanted them to be part of the story. He never wanted them to affect the outcome of a game.

"When seven officials walk out onto the field, for the most part, people don't even begin to notice them," McNally said in 2012 when he received the Hall of Fame's Pioneer Award. "This is the greatest thing I think for an official.

"Do the job. Hopefully nobody knows you're around. Make the proper calls the way they should be with a heavy dose of common sense. You're an NFL official. You're paid to be perfect."

McNally realized that officials were not always perfect. Steps toward the implementation of NFL instant replay were taken a decade before it was adopted.

To determine the length of video reviews, McNally personally experimented with instant replay during a 1976 Monday Night Football game between the Buffalo Bills and Dallas Cowboys. Camera technicians provided shots of close plays. A stopwatch was used to time decisions.

The NFL tested instant replay during the 1978 preseason. The experiment still needed work.

"The limitations with cameras and so on, you couldn't do much with it at all," McNally said. "Everybody agreed to forget about it."

NFL teams did not totally forget about instant replay. With improved technology and a booth official who could initiate reviews on site, owners voted to adopt a limited use of instant replay for the 1986 season.

"The difference this time is it wasn't the case of looking at a picture and television showing it," McNally said. "They had the capability of moving (the replay) forward, moving it back, slowing it down and full stop."

Officials reviewed 2,967 plays in 1,330 NFL games from 1986-91. There were 376 reversed calls. It amounted to 12.6% of the reviewed plays.

Instant replays still had flaws. The use of walkie talkies by the field officials and replay booth sometimes created miscommunication. The NFL determined that nine of the 90 reversed calls in 1991 were incorrectly overturned. Some thought the system delayed games too much.

Owners voted to eliminate instant replay after the 1991 season. The idea was not forgotten, though.

A new instant replay system was approved for testing during the 1996 preseason. It allowed coaches to challenge rulings on the field involving out of bounds and scoring plays and the number of players on the field.

Instant replay returned for the 1999 season after the NFL's competition committee addressed concerns from coaches and owners. Coaches' challenges were cut from three to two each half. A timeout was charged for unsuccessful challenges. Reviews of close plays were initiated by the booth during the final two minutes of each half.

With improved technology, officials now have clearer images and more camera angles to determine the outcome of replay challenges.

"The system we used from 1986 to 1990 was very good," McNally said in 2012. "It's nowhere good as there is now."

McNally continued to work for the NFL as assistant supervisor of officials from 1995 to 2007 and as an officiating observer through 2015. The officiating command center at the league's New York headquarters bears his name. So does an award the NFL presents annually to an official who exhibits "exemplary professionalism, leadership and commitment to sportsmanship" on and off the field.

Polian calls McNally "a monumental figure" in officiating.

"When he became supervisor, he personalized the entire process," Polian said. "So much so that with one exception, every major college conference today has a supervisor of officials who has been an NFL official.

"That's the respect Art McNally and the impact his process of scouting, developing, teaching and evaluating officials has had in our game, in every level of football.

"His enshrinement is really more about what he has done for the profession of officiating in virtually every sport."

Reach Mike at mike.popovich@cantonrep.com

On Twitter: @mpopovichREP

This article originally appeared on The Repository: 'Visionary' official Art McNally to enter Pro Football Hall of Fame