More than 8.7 million Americans with COVID-19 went undiagnosed in March, study says

Early in the year, all eyes were watching the novel coronavirus wreak havoc in Wuhan, China where the virus first hopped to humans from a mystery animal, while just a handful of cases were starting to emerge in the U.S.

Now, new research says the number of COVID-19 cases in March may have been 80 times greater than what original estimates revealed, amounting to more than 8.7 million new cases in the U.S. that health officials and the public never knew existed.

At the time, about 100,000 cases were officially reported, according to the study published Monday in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

The new estimates paint a grim picture of an invisible killer rapidly hopping from one victim to the next, long before stay-at-home orders and other preventative measures were implemented.

The researchers blame testing issues, high false-negative rates and asymptomatic spreaders for the “under-counting of the true prevalence of SARS-CoV-2,” according to the study.

“Our results suggest that the overwhelming effects of COVID-19 may have less to do with the virus’ lethality and more to do with how quickly it was able to spread through communities initially,” study co-author Justin Silverman, an assistant professor in Penn State’s College of Information Sciences and Technology and Department of Medicine, said in a press release.

“A lower fatality rate coupled with a higher prevalence of disease and rapid growth of regional epidemics provides an alternative explanation of the large number of deaths and overcrowding of hospitals we have seen in certain areas of the world.”

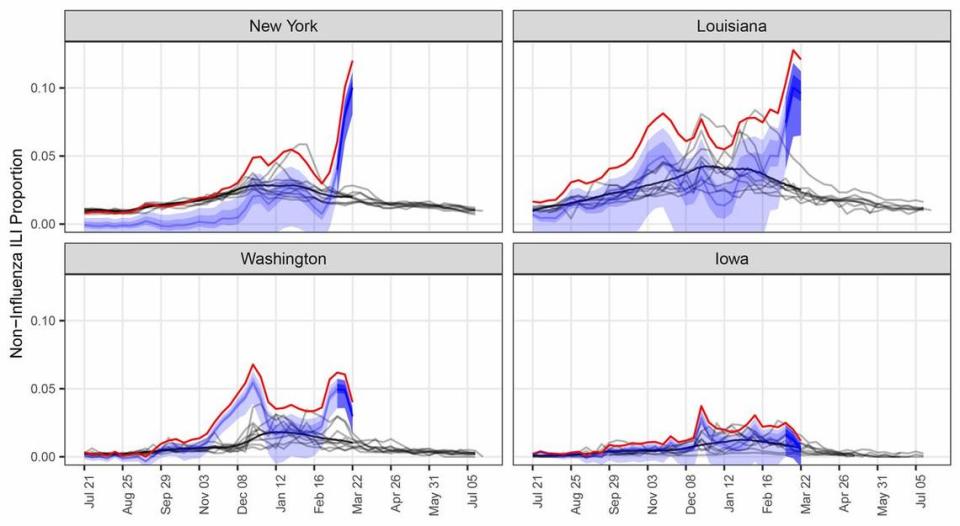

The team of researchers led by epidemiologists from Penn State University studied surveillance data on influenza-like illnesses (ILI) from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention over the past 10 years, according to the paper.

Then for cases in 2020, they subtracted those that could not be “explained by either influenza or the typical seasonal variation of respiratory pathogens” from the total to count likely COVID-19 cases, the release said.

The team soon identified a surge in non-influenza cases starting the first week of March compared to the past 10 years, correlating “with known patterns of SARS-CoV-2 spread across states,” the researchers said.

In the last three weeks of March, about 100,000 cases were officially reported in the U.S, according to the study, but the researchers’ estimates show that number actually stood around 8.7 million.

They also found that cases doubled nearly twice as fast as originally believed, the release said.

“At first I couldn’t believe our estimates were correct,” Silverman said. “But we realized that deaths across the U.S. had been doubling every three days and that our estimate of the infection rate was consistent with three-day doubling since the first observed case was reported in Washington state on January 15.”

The researchers also estimated infection rates for each state, which came out to be “much higher than initially reported but closer to those found once states began completing antibody testing,” the release said.

Many states such as Washington, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Colorado, New Jersey, and Louisiana “showed a surge in number of non-influenza ILI cases in excess of seasonal norms,” the study said.

During the last week of March, New York had about double the amount of outpatient visits that could not be explained by influenza or other seasonal illnesses than the state has ever recorded in the history of ILI surveillance data, according to the researchers.

The team’s “model suggested that at least 9% of [New York’s] entire population was infected by the end of March,” the release said. “After the state conducted antibody testing on 3,000 residents, they found a 13.9% infection rate, or 2.7 million New Yorkers.”

Together, the results show that the coronavirus had been rapidly spreading while undetected since the first case was reported in the U.S., and likely from individuals with milder symptoms than previously estimated, according to the study.