More Black Men Went With Trump This Time. I Asked a Few of Them Why.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

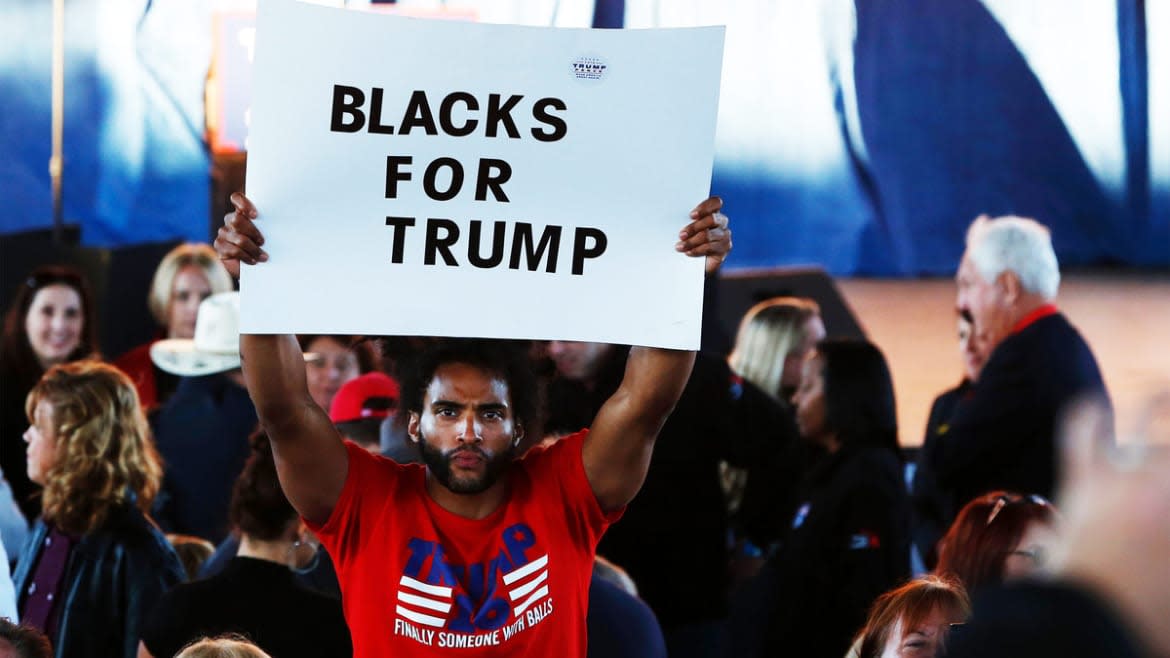

The number screamed at me and I actually wanted to yell back at The Washington Post exit poll, or, more specifically, those Minnesota Black male voters who comprised what, initially, looked like a glaring typo. In the state of George Floyd, which helped trigger yet another national awakening to the horror of police treatment of Blacks, 30 percent of Black male voters did the unthinkable. They voted for Donald Trump. It topped all the other states in the poll, with Nevada running second at 21 percent.

I looked again, shaking my head. Then I rushed to google “Black men in Minnesota.”

Chris Fields, an office manager of a law firm in Minneapolis, is part of that apparent 30 percent. He applauds the figures in the exit poll as a good piece of news for Republicans amidst the long-shot hopes that the president might rescue this election from fraud. Yes, Fields, like many Trump supporters, believes there may be some validity to the president’s claims of a stolen election, despite the mountain of credible sources and evidence that says otherwise.

In 2011, Fields, a native New Yorker, settled in the state after retiring as a major in the Marines where he served four tours of duty in Iraq. A year later, he challenged Keith Ellison for his House seat, knowing that the incumbent would prevail in an overwhelmingly Democratic district. Fields merely sought to start a broader conversation locally about the need for Black bipartisanship. Since then, he continued mounting that message throughout the state. In 2020, he steered the focus on converting young Black voters to Trumpism and, for the first time, found a receptive audience.

“My parents' generation would not hear of voting for a Republican,” Fields told me. “Younger generations, mine, my nephews, they are open to hearing a different message. They are more tolerant of listening to different ideas. If you see 50 Cent, Lil Wayne, Ice Cube, all those guys do is they give people permission, if you will, to say ‘I'll rethink this.’”

Overall, Biden won 87 percent of the Black vote. However, Trump also increased his share of the Black vote in notable ways. Nationwide, Trump won 19 percent of the Black male vote, up from 13 percent in 2016, and 9 percent of the Black female vote, up from 3 percent four years ago, according to exit polls.

The rising Black support for Trump in Minnesota could signal growing Black impatience with the perceived failures of white liberalism to rectify racial inequities. Minnesota’s entrenched liberal tradition runs deep. It was the one state—along with the District of Columbia—that Walter Mondale won against Ronald Reagan in the Republican landslide in 1984. However the dominance of the Democratic Party lives alongside the state’s notorious Black-white gaps in income and education. In Minneapolis, the median Black income in 2018 was $38,000 against $87,000 for whites. This $47,000 gap between the two was one of the largest in the country—second only to Milwaukee. A 2019 Federal Reserve Bank of Minnesota study found the state had one of the worst achievement gaps between Black and white students when it comes to college readiness.

Even Minnesotans who are not Trump fans and voted for Biden comprehend why there was a movement to Trump among some Blacks in the state. “Let me be clear, there is hard evidence about the incredibly damaging set of policies that Donald Trump has catalyzed in this country,” says Rose Brewer, a professor of Sociology and African American Studies at the University of Minnesota. “That can't be rationalized away. However people make sense out of the world in the conditions that they are confronted with. And when you dig very deeply, you see that white liberalism has not been able to unearth the really institutionalized structures of racism here.”

The racial disparities helped drive Cecily Davis, who voted for Obama in 2008, to the Republican side in 2012. “We have to decide what part of this pie do I want and why am I not getting it,” says Davis, who now chairs Minnesota’s chapter of Blexit, the Republican social media campaign geared toward converting Black Democrats to the GOP. “This causes you to lay down all of the emotion, and ask who’s in leadership? Why are we not getting our slice of the pie, and who’s in charge of that? That falls on the Democratic side and so it causes you to go to the other side to at least try something different.”

Thabity Willis, director of Africana Studies at Carleton College in Northfield, says when Black voters leave the Democratic Party out of frustration, they enter the GOP with lower expectations. “There are so many ways that the Democrats don't do what people imagine they should do,” Willis says. “Or at least what the establishment does. So in some ways, you can make an argument that people are more critical of the Democrats than they are of the Republicans because they have a higher expectation of the Democrats to begin with.”

Willis says when Democrats fail to meet the expectations of Black voters, the GOP is ripe as a refuge with an “anti-status quo” figure like Trump. “Like white male Trump supporters,” he says, “some Black men might also find something attractive in Trump’s anti intellectualism, which resonates with extreme forms of toxic masculinity.”

The questions of how and why the minority of Black voters supporting a Republican presidential candidate grew in 2020 resonates beyond Minnesota. Is this just a fluke, or are the hopes of Fields and Davis unfolding into something that will threaten the Democratic lock on the Black vote? The answer to that may lie beyond Trump and be more about Biden and Harris. Will their pivots to broaden their appeals lead to sending the kinds of political gestures to whites or conservative Democrats in ways that alienates Blacks?

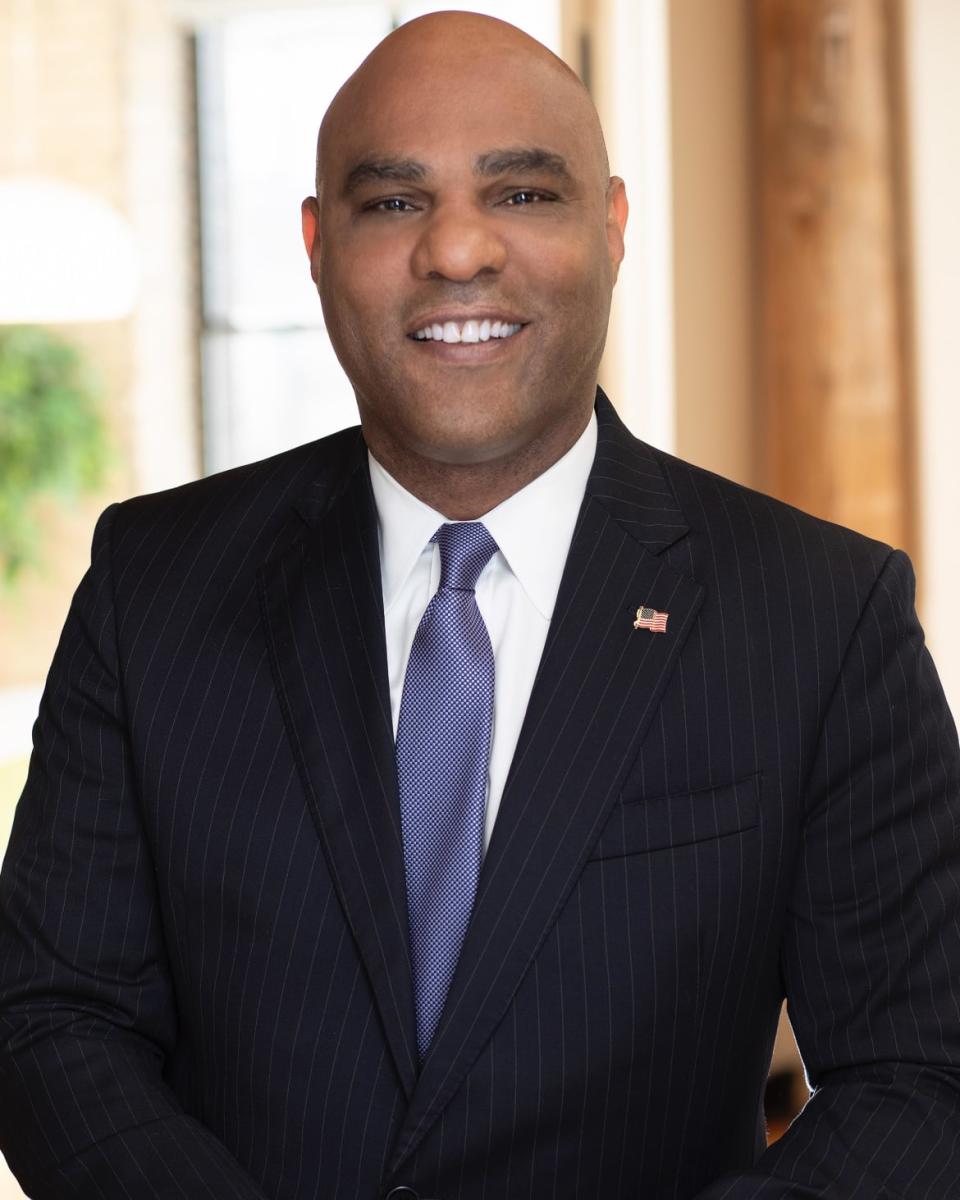

Vincent Hopkins, an entrepreneur who owns his own insurance and staffing businesses in Washington, D.C., sees Biden and Harris heading toward a “please everybody” route that will only produce failure. The result will continue, he believes, to erase some of the loneliness he feels being Black and an avid supporter of Trump and the GOP.

Hopkins actually has a lot in common with Vice President-elect Kamala Harris. They were classmates at Howard University. Like Harris, he glows with excitement when describing the Howard experience. Yet Hopkins grew in a totally different direction from Harris at Howard, where his attachment to the Republican Party was born. It was then that he realized, he says, that he was the product of parents with conservative values that they abandoned in the voting booth. At Howard, he felt the freedom in the classrooms to argue with his professors that abortion is not just murder: ”It is killing Black babies.”

Today, he and his wife, Maria, a captain now serving in Iraq as a physician, have a 3-year-old son, Colin, named after General Powell. If they have a daughter, they plan to name her Condoleezza. He thinks many of his good friends suffer from Trump Derangement Syndrome. “It means that no matter what Trump does, they hate him,” says Hopkins. “Even if he did something good, they hate him. There's nothing he can say or do that they would say good job or I agree with that. I mean it's almost a fanaticism.”

Hopkins concedes he can’t escape a tinge of pride in seeing his classmate, Harris, become vice president, but that feeling is far from enough to convert him. And, despite his strong support for Trump, he expects it will be easier for Republicans to make their case to Blacks with someone like Nikki Haley, one of his favorites, on the ticket in 2024.

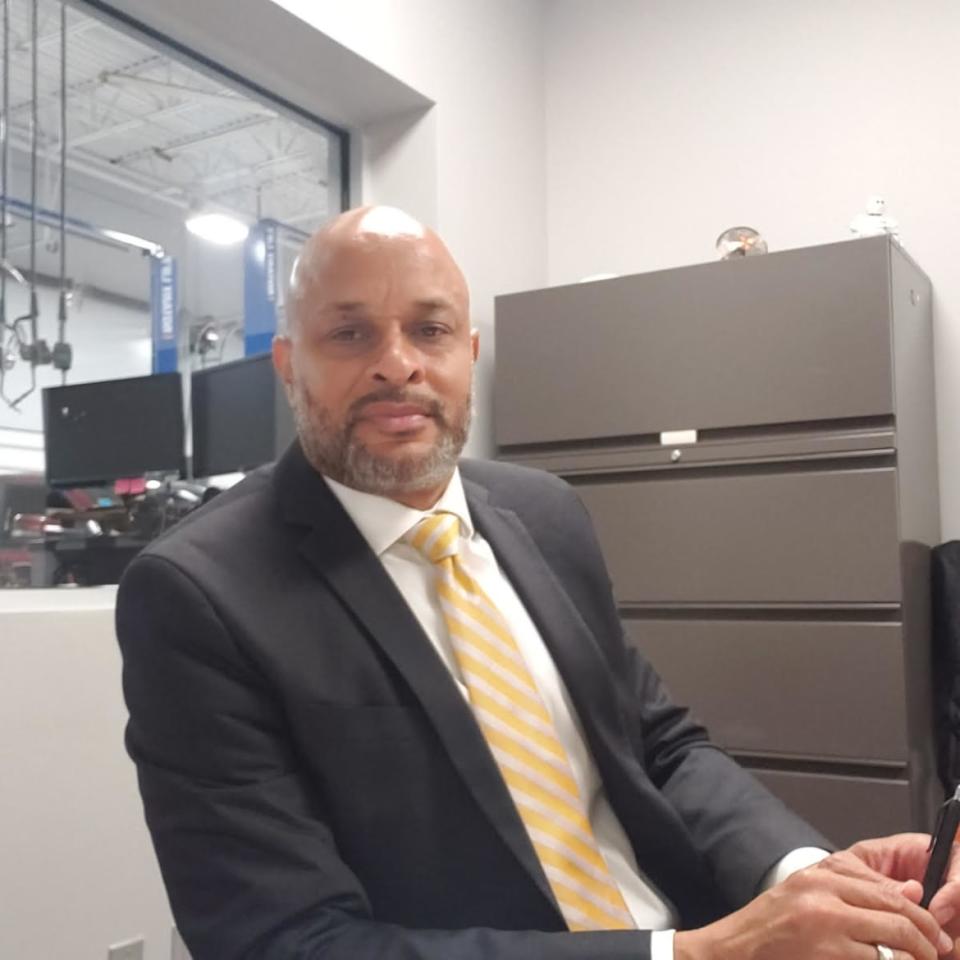

Unlike Hopkins, Mark Cameron, 54, who lives on the New Jersey shore and manages the service desk at an automobile dealership, is a registered Democrat and relative newcomer to voting for a Republican for president. He sees himself as an independent and moderate Democrat who voted for President Obama in both elections, “not because he was a Democrat, not because he was Black, but because he was the best man for the job.” He says that the same criteria—the best candidate running—led him to vote for Donald Trump in 2016 and again in 2020. “I didn't think that he would be as eloquent and as classy as Barack Obama,” says Cameron. “He wasn’t going to be a guy who I loved to hear speak. But I didn't vote for him for that. I've always been interested to see what would happen if we took the country out of the hands of a politician and put it in the hands of a businessman. Trump represented to me a possibility.”

Cameron says he voted for Trump in 2020 to see him fulfill his agenda and because Biden and Harris were turnoffs. “Though I’m a Democrat, I'm not really all that liberal. And quite frankly, there were some statements Biden made that I found a little surprising and could be interpreted as a little racist. He made an analogy about being in chains as an African American male in the United States today. I listened to the full statement and I know what he meant. But I still wouldn't expect any white guy to say that. Kind of turned me off. And then the statement about 'you're not Black if you don't vote for me.' That's not a statement that I would expect a white candidate to say when you're talking to the minority community. I almost feel, from my standpoint, that he's taken the Black vote for granted.”

Back in Minnesota, some Black voters clearly rejected the notion that Trump bore any responsibility for the discord after the murder of George Floyd by police. “Policing is a local issue,” Fields says. “The Democrats have nationalized it as if Donald Trump can make a phone call and anything in that police department can change.”

Fields even goes a step further and blames Democrats for the longevity of the careers of the officers responsible for Floyd’s death, such as Derek Chauvin. “The person who decided not to prosecute three of them was our own senator, Amy Klobuchar, when she was the Hennepin County District Attorney,” Fields says. “What I would say here is that the Democrats showed their true colors then and in allowing neighborhoods to be burned, and by allowing that precinct to be burned. They're not interested in protecting us.”

The resistance to seeing the relationship between racism and Trumpism also appears to shape the perceptions of Trump supporters in Minnesota’s large community of African immigrants. Minnesota has the largest Somalian community in the nation, in addition to more than 10,000 Ethiopian immigrants in the Minneapolis-St Paul area. While the exit polls did not differentiate between immigrants and native-born African Americans, both professors Brewer and Willis suspect that the Black immigrant population may play a role in the spike of Black voters for Trump. “It is harder for them to understand institutional racism,” says Professor Willis, “And oftentimes they have consumed global media and the negative depictions of African Americans as well before coming here. They have a distance with other Black and minority communities. To some degree, the gospel of the Republican center and right, the rugged individualism and bootstrapism, resonates with them because of their experience of picking up and transporting themselves here.”

Ayano Jiru, a Trump-backing Ethiopian immigrant in Minneapolis, says he was the lone voter for Trump in 2016 among his family of 21, which includes his siblings, parents, cousins, and uncles. He has spent the last four years promoting Trump in his family and community. In the family group chat on election day this year, he discovered the results of his lobbying—16 of the 21 family members voted for Trump.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.