More Latinos than ever serve on Ventura County city councils

For decades, the Oxnard City Council was a majority white institution governing a majority Latino city.

In 2018, that started to change. That year, the city expanded its council from five members to seven and divided the city into six council districts, with the mayor as the only council member still elected by the entire city.

Latinos make up a majority of registered voters in five of the six districts, and the first election under the district system resulted in Oxnard’s first majority Latino council. Today, Oxnard has two white council members and five Latinos, the exact inverse of the council’s ethnic makeup in 2017.

Oxnard isn’t alone. In 2018, every city in Ventura County had at-large council elections; since then, eight of the 10 cities have adopted district elections. Fillmore and Port Hueneme are the only cities left without council districts, though Thousand Oaks and Santa Paula adopted their district maps this year and haven’t had an election with them yet.

The goal of district elections is to empower voters and candidates who have traditionally been underrepresented. It seems to be working: The number of Latinos serving on a city council in Ventura County has more than doubled since 2017, from seven council members to 16. In 2017, Oxnard was the only city with more than one Latino council member. Now, five of the county's 10 city councils have two or more Latinos.

District elections appear to be the catalyst for this change in many cities, but Fillmore and Port Hueneme, the two cities without districts, also have more diverse councils than ever before, with two Latinos in office in Fillmore and three Latinos and one Black council member in Port Hueneme.

Ventura County's city leaders still don't quite look like their constituents — the county is 43% white, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, and the 10 city councils are 67% white, according to the Star's research. But the councils are a lot more reflective of the population than they were in 2017, when 87% of city council members were white.

Dave Rodriguez, a Camarillo resident who is the interim director of the Ventura County chapter of the League of United Latin American Citizens, said he thinks district elections are the primary reason that city councils are getting more diverse, but they aren't the only reason. Cities and districts with predominantly white populations have also been electing Latinos at a greater rate than ever before.

"We're hoping the public is going to continue to say, 'We don't care what that person's background is, we're going to elect them because we support them and we want to see them serve,'" he said.

'This huge, transformational thing'

The move to district elections is a statewide phenomenon, a delayed result of the California Voting Rights Act of 2001. The state law goes farther than the federal Voting Rights Act in requiring district elections when an ethnic group has not been able to elect its preferred candidates. The act can also require cities to enact other reforms, such as moving elections from odd years to even years to increase turnout.

The trend toward districts is likely to continue, after the Supreme Court of California ruled against the city of Santa Monica in its yearslong effort to avoid switching to districts. In an opinion issued Thursday, the court ruled that the California Voting Rights Act requires districts whenever a city has "racially polarized voting," which means ethnic groups tend to vote as blocs. Santa Monica had argued it should be exempt because it couldn't draw any districts that would be majority Latino, but the court ruled that isn't necessary.

Before the Voting Rights Act of 2001, only the largest cities in California, such as Los Angeles and San Francisco, had district elections. Over the past 20 years, more than 100 cities have ditched at-large elections, along with even more school districts, water boards and other elected bodies. Most of them have made the change in the last five or six years, as the cities who have fought against districts have lost a string of court cases, said Wesley Hussey, a political sciences professor at CSU Sacramento.

"It's this huge, transformational thing that's happening to local government in California, and it's not really being talked about," Hussey said. "I think even its supporters are surprised at how big it's turning out to be."

Not everyone is happy about the change. Some elected officials have argued their cities are ill-suited for districts because they could factionalize the community; because the city doesn't have racially polarized voting or racially segregated neighborhoods that would result in any districts with a large Latino population; because Latinos and other ethnic groups are already fairly represented in the city; or because it could be hard to find candidates for every district, especially in smaller cities.

Additionally, one academic study found that cities that switch to districts approve less housing than those that stick with citywide seats, because district elections empower not-in-my-backyard views of housing.

Many cities and school districts ditched at-large elections due to the implied or explicit threat of a voting rights lawsuit. "All it takes is one attorney" to send a letter demanding the change, Hussey said, "and there are several attorneys that do this for a living. Every city that's challenged them has lost."

The lawyer behind the letters

The most prominent such attorney — and the person who might be responsible for more changes to local government procedure than anyone in California — is Kevin Shenkman.

A partner in the Malibu firm Shenkman and Hughes, Shenkman often represents the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project. He also represents the neighborhood group that fought the city of Santa Monica all the way to the state Supreme Court.

Letters from Shenkman and his clients started the move to district elections in Ojai, Camarillo, Simi Valley and Moorpark.

Most city councils that get a letter from Shenkman or one of his fellow voting rights attorneys vote to adopt district elections immediately, before they can be sued. It can be costly to fight or even to delay.

The city of Camarillo missed a deadline to act on Shenkman's letter in 2018, and he sued. The city eventually adopted districts and settled the case, but it had to pay $233,000 to cover Shenkman's fees and other costs for the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project.

Shenkman said he got into the voting rights business by accident, when he got a call in 2011 from someone who wanted to sue the city of Palmdale for diluting the voting power of its Black and Latino residents.

After Palmdale lost a series of court decisions, it settled Shenkman's lawsuit by agreeing to move its elections to even years and adopt district voting, starting in 2016. That case paved the way for scores of cities to do the same.

"In Palmdale, the first election after that, a Latino won, and you started to see the east side of Palmdale finally getting its fair due," Shenkman said. "It had been neglected for many decades, but you finally started seeing parks and infrastructure and money that was being sucked out of the east side returning to that community."

'A dramatic positive effect'

The theory behind districts as a voting rights measure is that citywide voting can dilute the power of a group that might hold a majority in an individual district. If a city has racially polarized voting — and most cities do — then citywide voting can make it hard for a group that makes up a sizable minority of the population to elect the candidates of its choice.

For example, 23% of registered voters in Moorpark are Latino. If the city's voters are racially polarized, 23% might never be enough to win in at-large elections, when two or three seats are on the ballot. But if Latinos are concentrated in one part of the city, dividing Moorpark into districts could give them an opportunity to elect the candidate they want for that district.

That's how it worked in Moorpark. The City Council established districts for the 2020 election, and in District 4, which covers the central part of the city, 59% of registered voters are Latino. That district elected Antonio Castro as the city's only Latino council member; he was joined by Renee Delgado in the 2022 election.

Experts who study voting behavior have found similar cases all over California. A paper published in 2020 in the American Journal of Political Science found "a dramatic positive effect" on Latino representation in school districts that adopted district voting, as long as the school district had enough Latinos in one area to make at least one majority Latino district. If those conditions were met, district elections resulted in one additional Latino officeholder for every three available seats.

Another paper, published in 2021 in Urban Affairs Review, found that switching to district elections increased Latino representation on city councils by 10% to 12%, with a larger effect on cities with larger Latino populations.

Advocates of district elections say the benefits go beyond diversifying the ranks of elected officials. Pedro Chavez was elected last year to the Santa Paula City Council on a platform that included support for district elections, and this year he was part of a 3-2 majority that voted to adopt districts for the 2024 election.

"Districting allows for more accountability, because every individual in a community has access to their city council member, for their community," Chavez said. "If I live in a certain neighborhood, I know exactly who to go to."

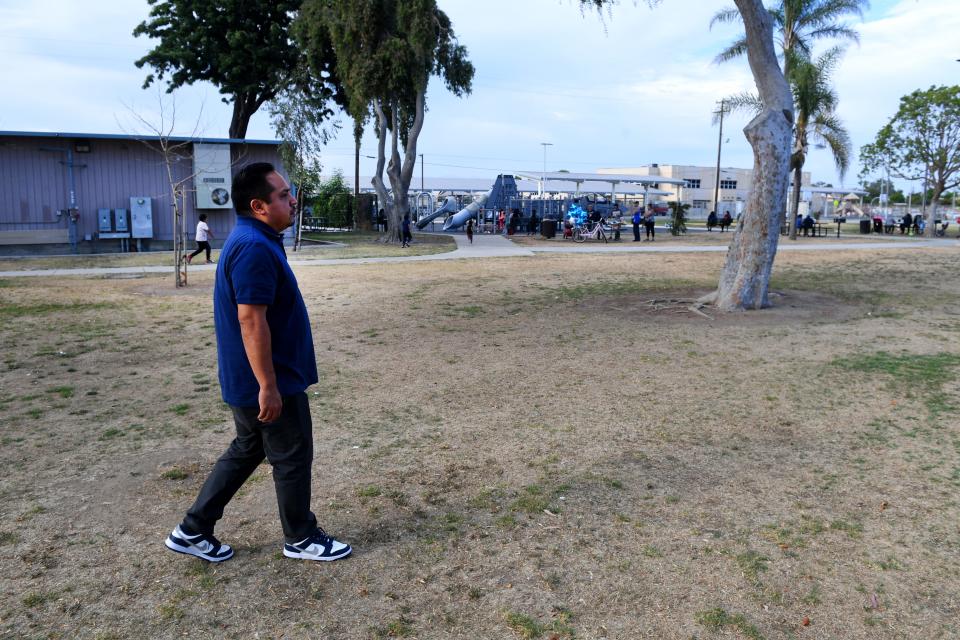

Oscar Madrigal was elected to the Oxnard City Council in 2016, before the city adopted districts, and re-elected in 2020 to represent District 3. He lives in La Colonia, a Latino neighborhood, and his district's population is 78% Latino.

Madrigal believes he's the first person to be elected to the Oxnard City Council while living in La Colonia; other mayors and council members grew up there but had left by the time they were elected.

"You go back and look at the history of the city, you see some disenfranchisement of this area compared to the rest of the city," he said. "Even to this day you can say Colonia is underserved, even though it's so close to the downtown."

Madrigal said district elections will make it easier for future candidates from neighborhoods like La Colonia, since they won't need to raise as much campaign money as they would in a citywide election.

"You can go door to door. You can get to know everybody," he said. "The first time, I had to cover the whole city, but I focused on the areas where I knew I would get the most support."

Even when carving a city into districts doesn't result in more ethnic diversity on the City Council, it can bring geographic diversity. In the city of Ventura, council members often lived in the downtown, midtown, hillside or beachfront areas. Now that the city has council districts, there are representatives from the east and west ends of town.

Liz Campos, a Ventura city councilmember who said she is biracial and declines to state her ethnicity on official forms, said she didn't think she would have a chance if Ventura still had at-large elections. Her district consists mostly of the Ventura Avenue area, a majority Latino neighborhood.

"I am confined in a wheelchair (spinal cord injury) and economically poor," she said in an email interview. "If we were not in districts, I do not believe other parts of Ventura would have voted for me."

'Our issues are citywide'

In Ojai, the City Council switched to districts for the 2020 election, and the resolution the council adopted in 2018 in agreeing to the change stated that it was doing so under duress, and that Shenkman's letter to the city contained "unsubstantiated allegations" that Ojai was in violation of the California Voting Rights Act.

The years since have not changed the mind of Ojai City Councilmember Suza Francina.

She was elected in in 2016 and re-elected to represent District 4 in 2020. Then in late 2021, she lost her home and couldn't find another one in the district.

Ojai is Ventura County's smallest city, with a little over 7,500 people, and Francina said her district doesn't have a single apartment building, so she couldn't find a place she could afford to rent. For about 18 months, she lived on a friend's property outside of her district.

There were calls to remove her from office, including from Ventura County's civil grand jury, though that ended when she recently found a room to rent in her district.

Part of the problem was that housing in Ojai is scarce and expensive, but Francina also blames the move to districts. In a city as small as Ojai, that makes it hard for a council member who has to find a new place to live.

"It's ludicrous to divide a 4.2-square-mile city into four districts," Francina said. "The last house I tried to get was right on the border of Ojai Avenue, and right across the street, just 20 feet away, there were two or three rentals I could not legally live in because they aren't in the district."

Francina said that if the city of Santa Monica had won its state Supreme Court case, Ojai would have revisted its decision to adopt districts. Ojai's population is about 75% white and 19% Latino, and among citizens of voting age, none of its four districts are more than 13% Latino. All of the city council members are white, just as they were with citywide elections.

"There are pros and cons for larger cities, but for our small town, the negative far outweighs the positive," Francina said. "There are very, very few issues that are limited to a district. Our issues are citywide."

Unintended consequences

Shenkman said he agrees that larger cities usually benefit more from districts than smaller ones, but he doesn't see "an appropriate bright line" that divides the two. When it comes to a situation like Francina's, he's unmoved.

"If you move out of your district, then maybe you're not eligible to serve that district, but then someone else will," he said.

There's also the possibility that switching to districts could make it hard to find candidates to run in every district. So far, that hasn't happened in any cities in Ventura County, but most cities here have only had one or two elections since adopting districts.

"Once you get down to districts with one or two thousand people, it's genuinely hard to find a qualified candidate of any race," said Asya Magazinnik, a professor of social data science at the Hertie School in Berlin, Germany.

Magazinnik has studied California's move to district elections extensively, and in a paper published this year by the Journal of Politics she and a co-author found an unintended consequence of district elections: They lead to cities approving fewer new housing developments, which could worsen the housing shortages that plague much of California.

The reason, Magazinnik said, seems to be that with at-large elections, large apartment complexes are likely to be built in lower-income neighborhoods that rarely send residents to the city council. With districts, those neighborhoods do have a voice on the council.

"There's this norm that the rest of the council can't roll the district representative for the district where they want to put the housing," Magazinnik said. "The district representative has to be OK with it going in their district. It's amazing that this developed pretty quickly after these cities adopted districts."

That custom — that a city council will show deference to one member when it comes to a project in that member's district — is common in big cities like Los Angeles that have had districts for generations. But city council members in Ventura County said they haven't seen it develop in cities here that have recently switched to district elections.

Madrigal said he doesn't think adopting districts has led Oxnard to reject any housing proposals that would have been approved under the old system. And he doesn't see himself or his colleagues approach their jobs as representing only their home districts.

"In Oxnard, we still have a lot of people on the council who were first elected citywide, so we feel like we're here to represent the entire city," Madrigal said.

"When you take an oath, you take an oath to represent all of the city," said Chavez, the Santa Paula council member. "The district is how you get elected, but the oath you take is took for the greater good of the community."

Tony Biasotti is an investigative and watchdog reporter for the Ventura County Star. Reach him at tbiasotti@vcstar.com. This story was made possible by a grant from the Ventura County Community Foundation's Fund to Support Local Journalism.

This article originally appeared on Ventura County Star: Latino representation grows on Ventura County city councils