More than a melee. What the Montgomery Riverfront brawl reminds us about nation| Robinson

Amelia Robinson is the Columbus Dispatch's opinion and community engagement editor. She is a life-long Ohioan.

I thought about how my grandfather changed his voice when he talked to white people as I watched a string of viral videos recently.

In them, a group of white boaters pummel and kick a Black riverboat co-captain, Damien Pickett, for doing his job at Riverfront Park in Montgomery, Alabama — a major spot during the domestic slave trade.

Brave Black people rushed to the co-captain’s aide. Others were so enraged by the evil scene — and no doubt centuries of racism — that they sought retribution and/or justice, making decisions that may have proven deadly when my granddad was a young man in Jim Crow Alabama, an age of lynching and terror.

More: Suspects detained after Saturday night brawl on Riverfront Park dock

Just hours before the attack and the awful melee that followed it, my husband and I visited Selma's infamous Edmund Pettus Bridge before heading to the Legacy Museum: from Enslavement to Incarceration and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery.

The haunting and beautiful sculpture garden — blocks away from the riverfront — features the names of the 4,400 Black people lynched in the United States between 1877 and 1950 carved in rust-colored steel.

More: Slavery's explosive growth, in charts: How '20 and odd' became millions

Afterward, we leered through a wrought iron fence at the First White House of the Confederacy before driving 20 miles to Prattville, the site of my late granddad's 1931 birth even though I rarely heard him mentioned it or anything about his life in Alabama.

Hope in the north

From what I did glean from him before his death, I know his life in Prattville and later Chattanooga, Tennessee was hard and often painful. Black people had a place. We were no longer slaves, but we definitely were not free to claim or exercise human dignities.

My grandfather and his six brothers and mother were among the millions of Black Americans who moved from the Jim Crow South to Ohio and other states in the Midwest, north and west during the Great Migration between 1910 and 1970.

My mom was an infant when my grandparents got their first home in Cleveland.

My ancestors sought opportunities away from oppression whitewashed by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and others who would have you believe Black people benefited from slavery; an economic system that saw children ripped from their mothers' arms to be sold, used, battered and abused to the day they died.

My granddad's changing voice

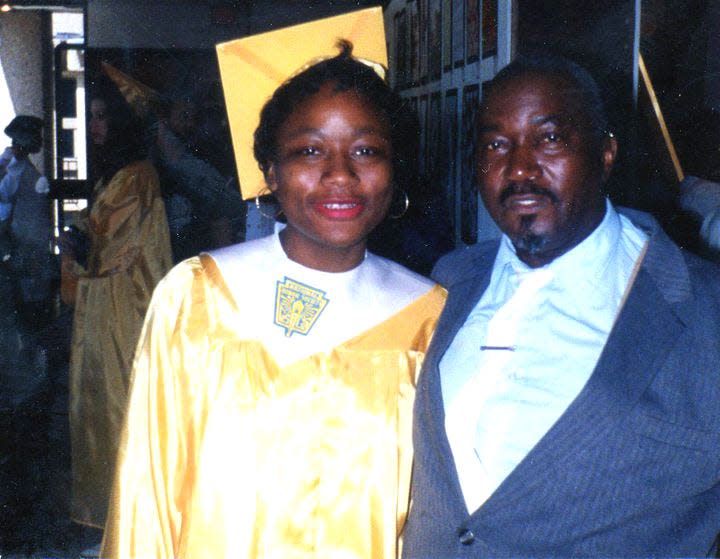

My grandfather died in 2004, but has never really left me.

I heard his sweet and strong voice in my head as we drove by Prattville's city hall and through its small, charming downtown. We stopped only long enough to take pictures at what is left of the Daniel Pratt Cotton Gin Manufactory.

Carl Ruth Robinson wasn't a subtle man, and neither was the way his voice shifted when he talked to white people.

I was a preteen helping him work on one of several homes he owned in our Cleveland neighborhood the first time I noticed how his voice shifted.

Before the phone rang, he was waxing on confidently about the news of the day and what was going on with this or that family member — what they should or shouldn't be doing to be exact.

It went beyond the code switching most people do to match their audience they are speaking to.

When he picked up the phone, my granddad was all "yes, ma'am" and "no, ma'am" the way the Black bellhops and waiters spoke in the classic black-and-white movies I've seen.

Submissive.

Flatly non-threatening even though there was nothing about the subject that the person on the other end should find threatening.

I took mental note that day the way America's Black children have taken note since people from the kingdoms of Ndongo and Kongo were kidnapped from Africa and the ship they were on was seized by two English pirates on the White Lion and the Treasurer and sold in Point Comfort near Jamestown, Virginia.

Rochelle Riley: Why America can't get over slavery, its greatest shame

There was no mention of the kingdoms of Ndongo or Kongo or how the White Lion and the Treasurer were American's slavery's Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria in my schoolbooks.

There were "lessons" in what is passed off as Black history but really it just scratches the surface when it comes to the history of America's white supremacy — slavery, Jim Crow, "separate but equal" and only the most well-known heroes who fought against it: Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, the abolitionists, Abraham Lincoln etc.

The psychological trauma

I was a sophomore at Ohio University the first time I heard he phrase "trans-Atlantic slave trade" along with other brutal historical facts - many of which would be restricted if Senate Bill 83 and other legislation pending in the Ohio Statehouse are approved.

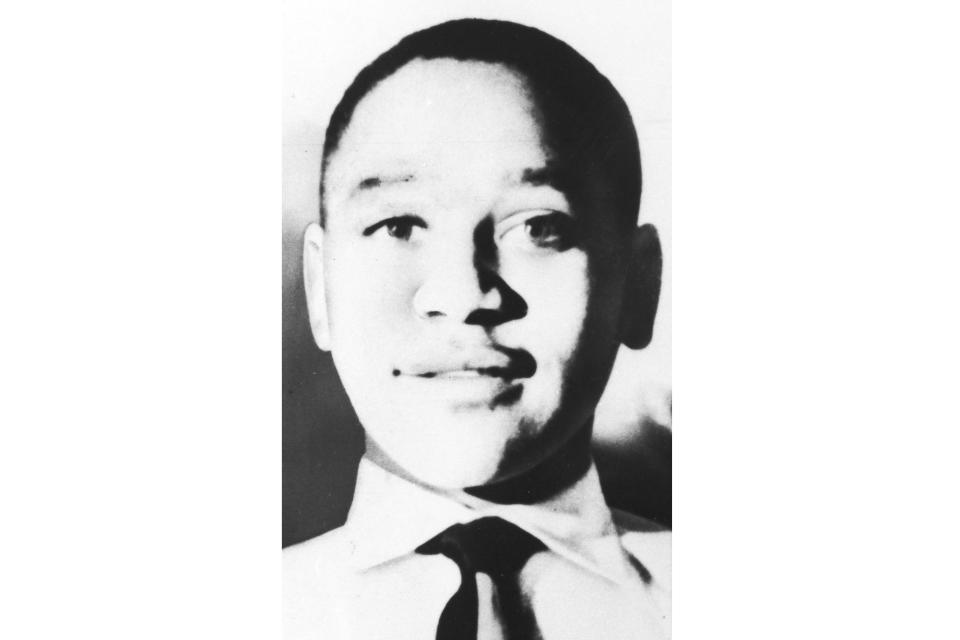

I did not know much about the psychological trauma that came with public lynching until researching for an article after investigators exhumed the body of Emmett Till - a 14-year-old Chicago boy accused of whistling at a white woman and lynched by a white mob in 1955 in Mississippi.

It was far more prevalent there, but lynching was not only a tool used in the South as a means to keep Black people in line, terrorized and submissive. Non-threatening.

As found for my 2005 article for the Dayton Daily News there were at least 17 black people killed by mobs in Ohio including a man accused, but never tried or convicted in the death of police Sgt. Charles Collis of Lagonda.

A mob of 4,000 watched as that man Richard Dixon (sometimes Richard Dickerson) of Cynthiana, Ky. was lynched.

As the Dayton Evening Herald recorded and I recounted, men and boys threw stones and emptied their guns into Richard Dixon's mutilated flesh. They joked with neighbors as his tattered clothes fluttered in the wind "like shreds of a battle flag."

Because they were Black

As described at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and in books some lawmakers here and around the nation don't want students to read, far less serious accusations could get a Black person — Black men in particular — lynched in my granddad's home state, this one and elsewhere around the nation.

Amelia Robinson: What grandma's big, sore feet say about love, health disparities

On April 1, 1892, an unidentified Black man was lynched in Millersburg in Ohio's Amish Country for standing around in a white neighborhood. According to reports, there were allegations that he would sneak "around town," and that he "stared at people."

A mob of 300 hung Frank Dodd from a tree in the "negro" section of DeWitt, Arkansas on Oct. 8, 1916 because he annoyed two white women the prior day. Several bullets were fired into his corpse. As the Arkansas Gazette reported on Oct. 10, 1916, "few white residents were aroused by the noise... Negroes in the town were greatly excited this morning, but the town was quiet tonight."

In 1894, Caleb Gadly was lynched in Bowling Green, Kentucky for creeping up behind his white employer's wife. As The Courier-Journal (Louisville) reported, "the lynching was so quietly done that neighbors and passersby were surprised this morning to see the body swinging from an oak tree over the Bowling Green and Three Springs pike, three miles from town."

After he had a white man arrested for attempting to assault his daughter in 1894, a mob of 30 "white cappers" shot up Jack Brownlee's house, beat down his door and took the Oxford, Alabama farmer to the woods where he was whipped, according to the Anniston (Alabama) Star.

An era of terror: Montgomery family remembers father's lynching, legacy

Elmore Bolling was gun downed on Dec. 4, 1947, in Montgomery, Alabama because he was successful.

In 1908, David Walker, his wife and four kids – an infant included – were shot as they fled their home in Hickman, Kentucky. The house was set on fire by a mob of 30 to 50 masked white men angry that Walker had used inappropriate language with a white woman. The Walkers' eldest son refused to leave the house and burned to death.

There are more than 4,000 other examples that remind us there was a time not too long ago that a group of white people could pummel a Black riverboat co-captain for just doing his job and nothing would have been done about it — legally or otherwise.

It always bothered me that my funny, loving and ridiculously smart granddad changed the inflection in his voice around white people.

Who could blame him?

There's a chance neither I nor any of his other descendants would be here today if he hadn't as a young, Black American male.

Amelia Robinson is the Columbus Dispatch's opinion and community engagement editor. She is a life-long Ohioan.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Montgomery Riverfront brawl a reminder of an era of terror in America| Robinson