More school districts are bringing back or adding police. Experts say it may not help

In 2021, the year after racial justice protests began spreading across the country, the District of Columbia City Council voted to gradually phase out school resource officers by 2025.

But this May, council members voted to repeal that plan after pushback from Mayor Muriel Bowser, who said in a statement last year that school leaders overwhelmingly opposed removing school resource officers because of fights on campus and concerns about student well-being.

Washington is one of several communities that have decided to reverse plans to remove school resource officers or increase their numbers as students return to classrooms this fall amid an increase in gunfire in schools. Law enforcement officials say their presence in schools has been complicated by staffing shortages and new restrictions, while experts say research shows there's little evidence it will increase school safety and may in fact harm students of color.

D.C. Council member Robert White, who supports removing and replacing police officers in schools but voted to repeal the plan to phase them out, said violence in schools has not ended because of the presence of police in schools. Still, he noted, many educators are worried about violence in their communities, want their students to be safe and see officers as "the closest city personnel to achieve the goals that they are trying to meet."

"I can be an ideologue and say 'No, I'm just going to oppose school resource officers, despite testimonies of teachers,'" White told USA TODAY. "But what that's going to end up with is permanent school resource officers. If we want to replace them, we have to create the new mechanism and get to there so teachers are comfortable."

Research: Is more school police the answer after Uvalde shooting?

School resource officers return to campus

Days after George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis in 2020, the city's school board unanimously voted to end the district's contract with the Minneapolis Police Department, prompting a wave of other districts across the country to follow suit. At least 50 districts went on to end school police programs or reduce the programs' budgets, Education Week reported last year.

But by June 2022, at least eight districts in states including Virginia, California and New York had reversed course, Education Week found.

This June, Denver joined that growing list when a split-decision school board vote reversed a 2020 policy prohibiting armed officers on school campuses, the Denver Post reported. The heated and emotional debate was connected to a shooting at a Denver high school earlier this year, according to Auon'tai Anderson, a school board member who voted against the reversal.

Defund police in schools? How the movement got momentum after George Floyd's death

Anderson said data showed the decision to remove officers had the intended effect of reducing the tickets and citations arrests, which disproportionately affect Black students. But he said there is no evidence to suggest the presence of a school officer could have prevented the shooting in March.

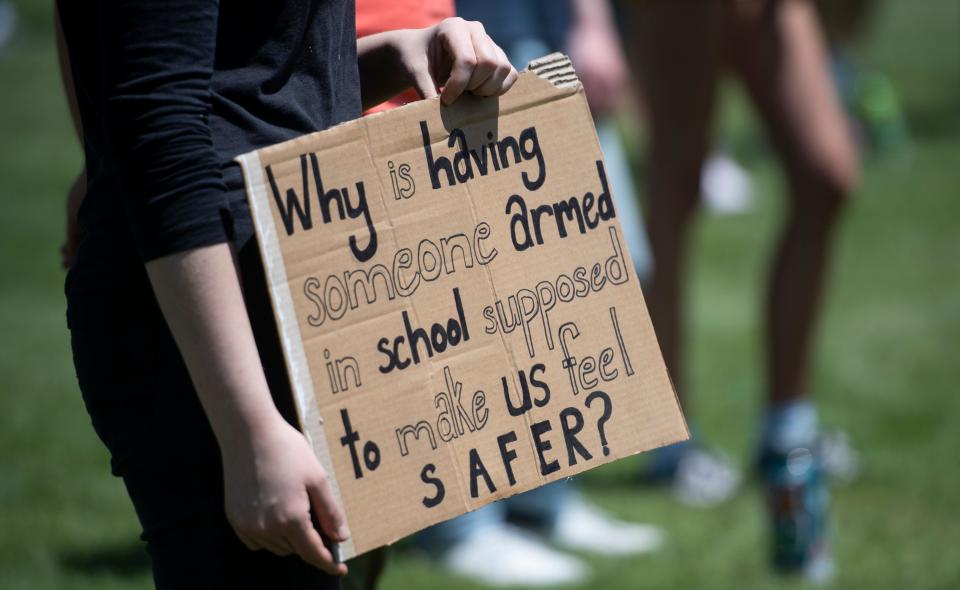

"This conversation to return SROs was not based in science or the fact that they prevented anything but based in fear," Anderson said. "We believe this is the best preventable cure to stop mass shootings, which is just not true."

Nearly half of parents said they fear for their child’s safety at school, the highest percentage in nearly two decades, according to a 2022 Gallup poll. Although officers reduce some forms of violence, such as physical attacks and fights, they do not prevent gun-related incidents, according to a 2021 study from the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit think tank, and the University at Albany.

"The best evidence that we have to date shows no deterrent effect of where gun violence happens in schools or where weapons are brought to schools. ... Similarly, when a shooting does happen in a school, those shootings, actually, on average have been more deadly in schools with police," said Ben Fisher, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor who recently reviewed dozens of studies on the effects of police in schools.

This question gained national attention this year during the trial of a former school resource officer who did not confront the gunman during the deadly 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, and the investigation into the failures of law enforcement when a shooter killed 19 children and two adults at an elementary school last year in Uvalde, Texas.

"There is this idea, especially in our country, that the police are going to be the ones to solve a variety of social problems. That includes school violence," Fisher said.

New laws present challenges in Texas, Minnesota

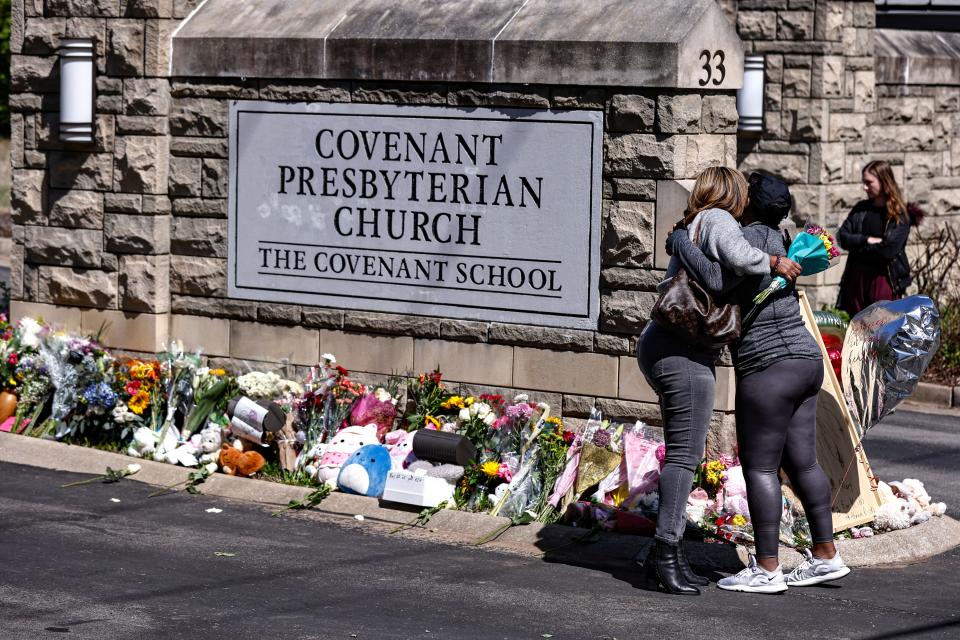

Lawmakers in some states have also passed and proposed legislation to increase police presence in schools. In Kentucky and Texas, new laws require all schools to have school resource officers. In Tennessee, where a shooter killed six people at a Nashville elementary school in March, a lawmaker recently proposed legislation to allow police to assign officers to work at schools, even if the school board doesn't have a policy or agreement with the department.

But as the demand for school resource officers appears to have increased, staffing has been a challenge, according to Mo Canady, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers.

"We are in a huge law enforcement recruiting crisis across the country, not just for SROs but for law enforcement officers in general," Canady said. "So you know, while we certainly want to see more selected and specifically trained SROs in the school environment, finding them is now becoming problematic."

The Nashville Metropolitan Police Department faced backlash last month for deciding to forego millions in new state funding for school resource officers because the agency cannot staff the area's 70 public elementary schools, reported The Tennessean, part of the USA TODAY Network.

Texas gave districts about $15,000 per campus in additional funding as part of a new law requiring school resource officers, which took effect Sept. 1. But Dan Turner, chief of Alief Independent School District Police Department, said that money "is basically not enough to do anything with when it comes to hiring a police officer."

Turner said the school district, which is based in southwest Houston, has approved additional funding to cover the cost of hiring about 30 officers to cover all of the district's elementary schools. Li Wen Su, a spokesperson for the district, said the additional positions approved to meet the new requirements have an estimated cost of $2 million.

Turner said actually finding officers to hire has been the biggest challenge.

"We're in competition with all the districts in Texas," he said.

The law allows exceptions, but it's unclear how many schools weren't able to meet the standard because districts are not required to report if they meet the state’s new requirements of having armed officers on every campus. The Associated Press reported at least half of 60 of Texas’ largest school districts were unable to meet the law’s highest standard at the start of the school year.

Jeff Potts, executive director of the Minnesota Chiefs of Police Association, said parents and school districts have become more receptive to having officers in schools because of "the threat of violence." But he said law enforcement agencies removed officers from dozens of schools before the start of the school year as a result of a new state law. The law prohibits officers from physically restraining students in certain ways, including face down in the "prone position," and allows them to use reasonable force to restrain a student "to prevent imminent bodily harm or death."

Potts said the law has officers concerned that they or their department could face criminal or civil repercussions if they act too soon to prevent a conflict from escalating or that students could be harmed if they wait too long to intervene. Potts has asked the governor to intervene and provide a legislative solution.

"Our hope is to get back to a place here very quickly through a special session that the SROs will go back, because I think they'll be welcomed with open arms," he said. "It's just right now we're in this kind of awkward period where the new law has really changed that."

School resource officers can have 'unintended negative consequences'

Aaron Kupchik, a professor of sociology and criminal justice at the University of Delaware, said adding officers in schools probably will bring "unintended negative consequences."

The RAND and University of Albany study also found school resource officers increase the use of student suspensions, expulsions, police referrals and arrests, punishments that disproportionally affect Black students, male students and students with disabilities. Kupchik said that while suspension or arrest may sometimes be necessary, these solutions are used too frequently, which causes harm to some students and school communities.

Canady said school resource officers should be dealing with "disruptions that lead to criminal activity," not discipline problems that should be handled by the school. He said specific training related to implicit bias, working with children and adolescent mental health along with the relationships formed with students can help prevent negative interactions.

"Most SROs refer to the student body as 'my kids,'" Canady said. "And at that point, it doesn't matter. Culture, ethnicity and nationality, those things are out the window once you begin to approach it in that way."

Though the relationship building touted by many school resource officers sounds positive, Fisher, the University of Wisconsin-Madison professor, said these interactions aren't always beneficial to students.

"I remember one officer talking about how he essentially builds relationships with certain students because they funnel him information about problems that are going on in school," he said. "So this isn't relationship building just for the sake of being a positive role model for students, but it's to help the officer solve crimes or catch the kids who are doing something that they've deemed inappropriate."

Kupchik said there are steps educators can take to preserve the school social climate, which is important for keeping schools safe.

"Act restoratively rather than suspending them or turning the behavior over to the police to do it. Things like that can be helpful," he said. "These are solutions that we have had for literally decades, and they get put on the shelf because of the allure of suspending children and arresting them."

Contributing: The Associated Press

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: More school districts are bringing back or adding police. Will it help?