More than three years into its orbit, a bread loaf-sized UNCW satellite enters new chapter

Hurtling through space miles above Earth's surface, a bread loaf-sized satellite run by the University of North Carolina Wilmington is flying into its next chapter.

The satellite was launched into orbit in 2018. But this week it's celebrating a one-year anniversary of officially entering its operational phase -- a designation that means the satellite is ready for the work it was sent to space to do.

Dubbed Seahawk-1, the satellite orbits Earth once every nine days and takes images of land and water below using an ocean color sensor researchers have named Hawkeye.

The images are used by ocean color researchers in Wilmington and throughout the world.

The ocean color field studies images of the ocean to understand how it's changing and how changes impact people, especially those in coastal areas, said Phil Bresnahan, an assistant professor of oceanography in UNCW's Earth and Ocean Sciences Department.

UNCW: UNCW names former College of Liberal Arts and Sciences dean as chancellor-elect

In other news: Whale that washed ashore on Masonboro Island used for study, and even for shark bait

Bresnahan will take over as the satellite's principal investigator when John Morrison, a former professor in UNCW's Department of Physics and Physical Oceanography, officially retires at the end of this month.

Morrison has led the satellite program since its inception. He retired from teaching four years ago but returned part-time to guide the university's work on the satellite.

The satellite's next chapter will focus in on using the collected images for research.

“Now we're entering into a new phase of actually doing the scientific research that the satellite enables,” Bresnahan said.

Bringing small satellites to 'prime time'

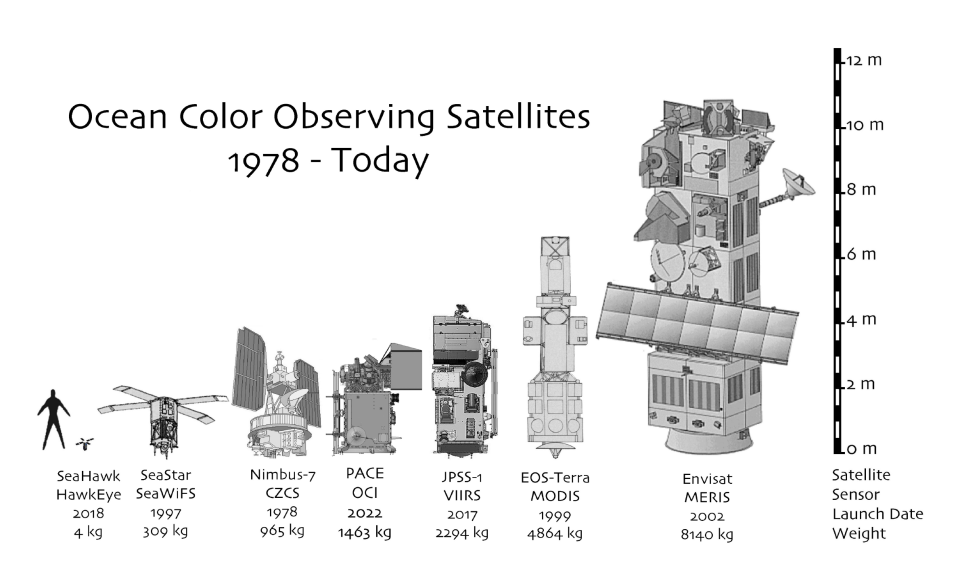

When work began on the SeaHawk-1 concept in the early 2010s, the size and cost of satellites was on the rise.

It wasn't unusual for NASA to launch bus- or refrigerator-sized satellites into orbit as part of multi-million or multi-billion dollar projects, said Gene Feldman, an oceanographer emeritus at NASA.

“The evolution within NASA … has generally been to build bigger and bigger satellites, and more and more expensive satellites,” he said.

Feldman and Morrison met working on a desk-sized ocean color satellite called Seawifs. When that project ended, the two decided to join forces to launch a less expensive, miniature satellite called a Cubesat to capture ocean color images.

Many researchers at the time didn't take Cubesats seriously. They didn't believe the technology was ready for "prime time," Morrison said. His team set out to prove them wrong.

The idea received $1.8 million in funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation in 2014. Gordon Moore was a co-founder of technology company Intel.

“They had an interest in seeing whether Cubesats were primetime, that you could actually do something with a CubeSat that wasn't just a play toy,” Morrison said.

From design to launch

Seahawk-1 is a cube that, in inches, measures roughly four by four by 12.

While the project was still in its conceptual stages, researchers faced challenges in designing an image scanner that would capture high-resolution pictures but only take up roughly a third of the satellite's space, Feldman said.

Sara Rivero-Calle joined the Seahawk-1 mission as a postdoctoral student at UNCW. She helped build the satellite and still runs the satellite's photo scheduling as an assistant professor at the University of Georgia's Skidaway Institute of Oceanography.

Rivero-Calle was drawn to the satellite project because it represents collaboration between a public university in UNCW, a government entity in NASA and Clyde Space, the private company in Scotland that built the Cubesat.

That type of collaboration can be rare, Rivero-Calle said. It's also uncommon to get the opportunity to be part of the design, launch and data gathering of a satellite operation, she said.

“Being part of a mission, from the beginning, from the design until you get the images takes a really long time for the bigger missions," she said. "But Cubesats are unique in that this whole process is a lot shorter.”

Seahawk-1 was launched into outer space in December 2018 on a rocket that carried 63 other spacecraft. But the satellite's work didn't begin right away.

It took two and a half years for the satellite to calibrate its image sensor and gain the stability needed to take clear, high-resolution images of Earth's surface.

“We had a lot of teething pains in the beginning of the mission,” Feldman said. “We basically had a two and a half year commissioning phase when normally it should have taken just a couple of months.”

More than proving a concept

The satellite began as a way to prove a scientific concept, and it's succeeded.

Seahawk-1 transmitted its first image to researchers in April 2021. Since then, the satellite has captured more than 4,000 images, collecting about 100 new images each week, Feldman said.

The satellite has shown the smaller, less expensive Cubesat can be used for data gathering and real scientific study.

“I think we not only proved the proof of concept, but we've gone beyond that, to prove that it can become an operational, very credible scientific mission,” Feldman said.

The satellite doesn't continuously collect images. Instead, Seahawk-1 must be programmed to capture specific stretches of the earth. Anyone can make a request for a satellite image in an online system maintained by Rivero-Calle.

Initial funding for the project is set to run out this summer, Morrison said, but Bresnahan and Rivero-Calle have submitted a new funding proposal to the Moore Foundation to use images taken from the satellite to research coastal areas, including parts of Southeastern North Carolina.

The image sensor on Seahawk-1 provides images of coastal areas at a higher resolution than any other satellite in orbit, Bresnahan said.

“We have more pixels per kilometer than any other ocean color sensor that currently exists,” he said. “That means we can see sharper features, finer features on the surface of the ocean.”

Each pixel in images produced by Hawkeye captures 120 meters of the Earth's surface. Other image sensors produce a single pixel for every kilometer.

That fine detail is important when studying what Rivero-Calle calls "optically complex waters" that have high amounts of sediment or plankton in the water. It's also key when looking at waterways that appear narrow from space, Bresnahan said, like Wilmington's Cape Fear River and Intracoastal Waterway.

A new kind of beach patrol: Oak Island's new Beach Services Unit aids in public safety

More from Emma Dill: A growing corridor: New York firm looks to bring modern industrial park to U.S. 421

Bresnahan and Rivero-Calle hope to continue moving the satellite into its future research phase if they get funding for their proposal.

But the future of the satellite remains unclear.

Typically, Cubesats have lifespans of a couple years. Seahawk-1 has been in orbit for three and a half years. The technology hasn't given any signs of failing, Feldman said, but the satellite does sometimes encounter glitches that take it offline for days or weeks at a time.

“It could end tomorrow, it could go for another year or two, we don't know,” Feldman said. “Every day is a gift from this point forward.”

“What is going to happen is some catastrophic failure of some system onboard. The computer may be hit by a radiation burst, and it'll have a problem. A solder joint may break over time," he said. "It will be something unexpected, but catastrophic.”

Reporter Emma Dill can be reached at 910-343-2096 or edill@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: UNCW satellite enters new phase after three years in orbit