Mosques, Jackson help Miami Muslims get vaccinated, but more outreach needed, experts say

Farzana Ghani, a 52-year-old volunteer at the Islamic School of Miami’s food pantry, had plenty of reasons to get the COVID-19 vaccine: She has a background in science and research, her eldest daughter is a physician assistant who had already gotten her shot and Ghani’s work with the public likely increased her odds of getting the deadly virus.

But when she showed up to her vaccine appointment in late February at a Miami-Dade hospital, the small talk with the nurses while she waited in line quickly turned into their “mixed reviews” on the vaccines side effects. This, coupled with her own inherent skepticism, was enough to get her to leave the hospital, without a shot in her arm.

“I just walked away from there and I said, ‘I don’t want to do that,’” said Ghani. (Her daughter, she added, was not happy with her.)

It wasn’t until Ghani began attending town halls hosted at the Islamic Center of Greater Miami in Miami Gardens, in partnership with the UHI CommunityCare Clinic in Miami Gardens and the Coalition of South Florida Muslim Organizations, that she opened up to the facts. She heard it from her imam, she heard more nuanced explanations from medical experts and she heard it from public officials: The COVID-19 vaccines are safe, they do not contradict Islamic beliefs and, most importantly, they’re effective at protecting against a severe case of COVID-19.

Although there’s not much reliable data available on how Muslim Americans feel toward the vaccine, there’s enough anecdotal evidence to suggest that Ghani’s case is not unique. Like many other Americans, some Muslims in the U.S. have not been immune to misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccines, including false claims that some ingredients in the vaccines are haram, or forbidden by Islamic law.

Some experts say that even as mosques and civic organizations have secured access to vaccines and demand is now dwindling, addressing hesitancy and establishing trust with Muslim Americans remains one of the biggest hurdles to increase vaccination rates among Muslims in the long term.

“America has not been generally kind to American Muslims. So there’s a big distrust of government, big distrust of industries,” said Dr. Hasan Shanawani, president of the American Muslim Health Professionals and director of the National Muslim COVID Taskforce, a coalition of medical experts and religious leaders created last year to help Muslim leaders navigate pandemic measures.

The ‘long haul’

In South Florida, the virtual town halls hosted by the Islamic Center of Greater Miami helped bridge that gap by bringing health workers and experts on Islam to speak with members of their mosque about the importance of getting vaccinated. Back in February, the mosque helped advertise a virtual conversation by Dr. Anthony Fauci, chief medical adviser to President Joe Biden, to answer questions from the Muslim community, which was hosted by the American Muslim Health Professionals.

And by some measures, that drive appears to have been successful. In the past three months, the Islamic Center of Greater Miami has helped vaccinate about 1,700 people at Jackson South, and an estimated 70% of them identified as Muslim. At first, though, according to Khalid Mizra of the Islamic Center, mosques had been largely excluded from initial efforts in Miami-Dade County to give vaccines to houses of worship.

“We were not part of that” first initiative, Mizra said. He added that the mosque reached out to Jackson Health System and they were ultimately included in the rollout. They were also part of Gov. Ron DeSantis’ interfaith vaccination event at Aventura Turnberry Jewish Center on Feb. 4.

And while there’s significant Muslim representation in the healthcare industry, about a fifth of all Muslim Americans are Black, according to a 2019 study by the Pew Research Center, a community that has seen some of the lowest rates of vaccination in Miami-Dade County, according to ZIP code data analyzed by the Miami Herald.

“This is a long haul and there are trusted sources within the community that we need to be partnering in more substantive ways,” said Dr. Aasim Padela, an expert on Islamic bioethics and Muslim health disparities at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “Religious leaders don’t want to be here just to rubber-stamp some healthcare initiative…That’s often why the Muslim community is largely left out. There are no durable relationships.”

On the right track

There’s some reason to believe those relationships might be fizzling out. One of the larger vaccine providers in Miami-Dade, Jackson Health System, is ending its vaccination program on May 21. The county is expected to pick up the thousands of doses Jackson had been getting each week.

Jackson’s departure from the vaccine front may impact community partnerships with places like the Islamic Center of Greater Miami, which the hospital system launched to address vaccine inequities across South Florida.

Shabbir Motorwala, of the UHI CommunityCare Clinic, said although the Islamic Center has stopped taking new vaccination appointments, he’s proud of the health clinic’s efforts in the Muslim community and believes much of the skepticism he saw in the first weeks of their campaign has largely faded.

“In the Muslim community, I think we are on the right track,” said Motorwala. “We were able to reach out and successfully vaccinate a great number of the Muslim community. And it’s still ongoing.”

Motorwala said the clinic in Miami Gardens, where the mosque is located, is still receiving vaccines from the state Department of Health and has continued to take in new patients. And through Ramadan, which is the holiest month of the Islamic faith and ends May 12, it has been significant that leaders of the faith have framed vaccination as an important duty.

“Now, it’s positive because the majority of Muslim scholars took a position that [misinformation], it is fake news,” Motorwala said. “It came globally. Muslim leaders in Muslim countries, they came out strongly in favor of getting vaccine.”

Just like a Dunkin’ Donuts store

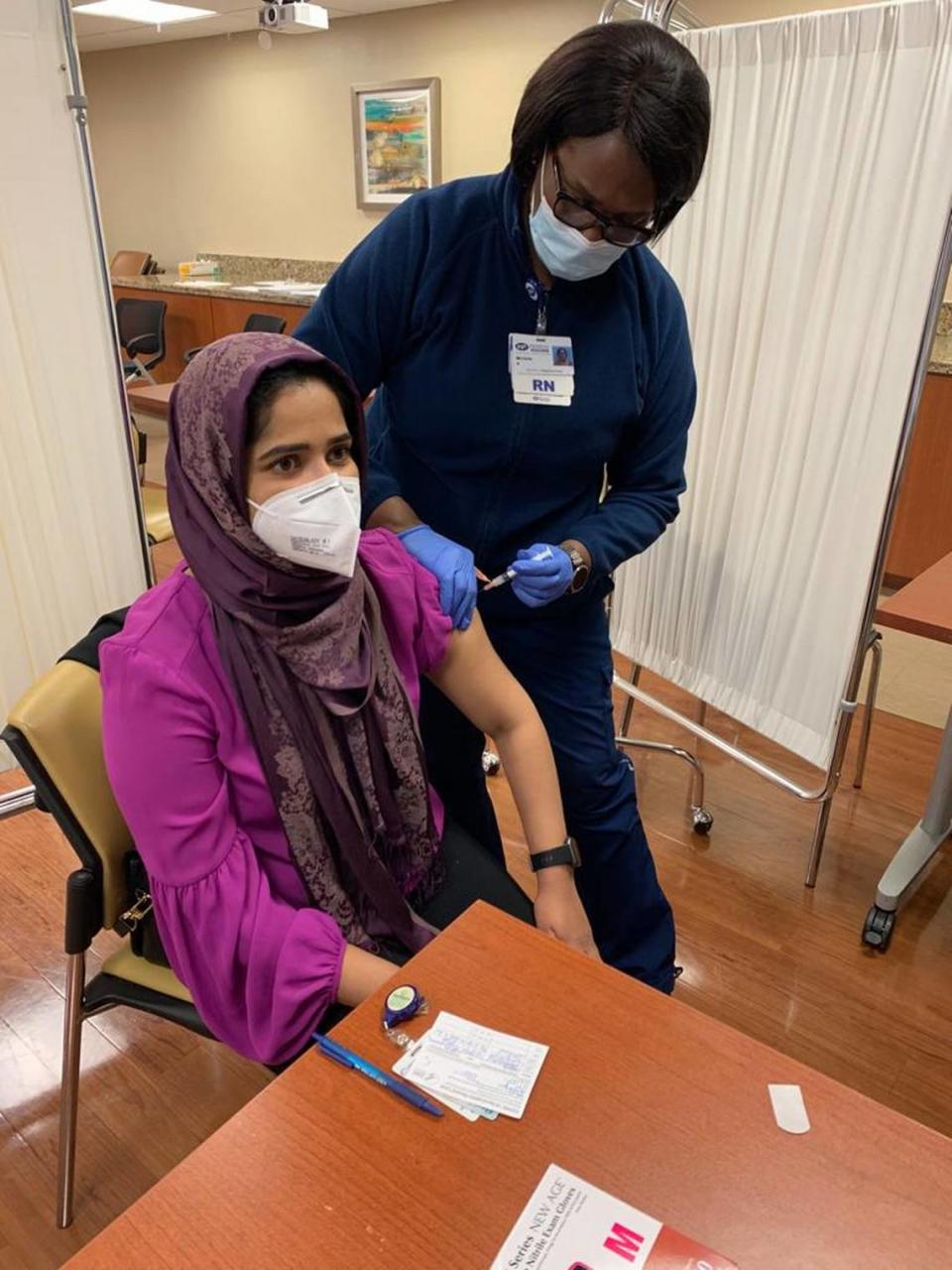

Once she was armed with information, Ghani, the food pantry volunteer who had once been hesitant, decided to give the vaccine one more try. In mid March, she got her first dose of the vaccine and has since completed her full dose, which did give her some body pains and a headache.

She admits it was ultimately her daughter, the PA, who convinced her.

“She told me, ‘Mom, so much research has been done.’ They spent their life and time doing research about these vaccines. And it’s safer,” Ghani said. “I have to be more responsible for other people too.”

But Shanawani, the director of the National Muslim COVID Taskforce, said he believes Ghani’s experience was emblematic of what can happen when healthcare workers gloss over people’s concerns. He compared it to walking into a Dunkin’ Donuts and walking out without being sold coffee or a doughnut. “There’s something wrong with that store,” he added.

“[People] expect to be skeptical about something that they don’t understand. And that’s not a bad thing, that’s actually, in general, a safe way to be,” Shanawani said. “But the onus is on [medical professionals] to really demonstrate that this is safe, that it was thought out.”