Mosquito control program polluted SC lake with chemicals, lawsuit says. Duke Energy blamed

For more than 90 years, a power company took pride in the mosquito control program it used to fight malaria around a string of lakes the utility oversees from north of Charlotte to Lake Wateree near Camden.

Unfortunately, some of the concoctions used to kill mosquitoes also spread cancer-causing material that polluted fish in the Catawba River and many of the basin’s lakes, according to a 2021 scientific research paper.

Now, a handful of Lake Wateree residents are suing Duke Energy, seeking potentially millions of dollars in compensation. They say pollution from mosquito spraying has hurt their property values and tainted fish at levels that make some popular species unsafe to eat.

The lawsuit, filed last week in Kershaw County, centers on Duke’s use of mosquito-killing transformer oil that contained PCBs, powerful, long-lasting toxins tied to cancer, skin rashes, liver damage and other ailments.

The residents say Duke should have known that its spraying would spread hazardous PCBs. But the company continued to conduct the program — and it concealed the fact that the oily substance it spread on the lakes, including Wateree, contained the toxic material, the suit said.

“The contamination poses a significant risk to human health and resulted in a continuous and ongoing interference with the (residents’) property rights,’’ the suit says, alleging that Duke’s “illicit disposal of PCBs into the environment .... was done with knowledge or with reckless disregard for the potential harm caused by PCBs.’’

Camden attorney Vincent Sheheen, a former state senator whose law firm is among three handling the case for the residents, said he’s seeking what’s known as “class action’’ status, which would grant potentially thousands of property owners payments, in addition to the three residents who sued, if approved by a court. Class action suits can result in millions of dollars in damages against companies being sued.

The Savage, Royall and Sheheen law firm, along with Speights and Solomons, and the Strom Law Firm, filed the suit on behalf of Kershaw County residents Clyde Marcus Jones II, and Dennis and Deborah Phillips.

Duke spokesman Ryan Mosier said this week the utility will look into questions raised in the lawsuit.

“Duke Energy takes environmental allegations seriously and we are investigating these, which relate to a historic program for our lake system,’’ Mosier said in an email. “As we review details of the litigation, we will thoroughly review the mosquito control program, the subject of these allegations.’’

Lake Wateree, built in 1919, is 30 miles northeast of Columbia at the bottom of the Catawba-Wateree river chain of lakes. Popular with boaters and fishermen, the 13,000-acre lake also has a substantial residential community. Thousands of people live along and near its shoreline.

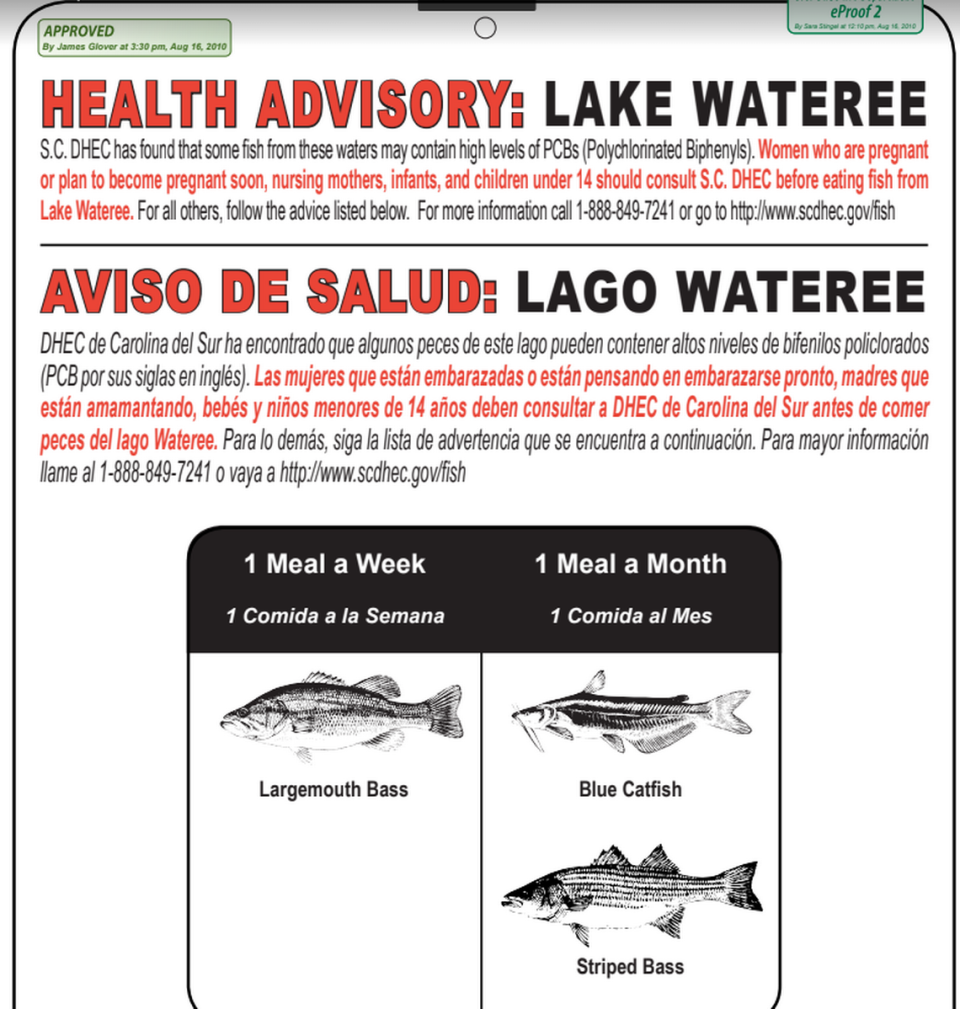

PCBs have become such a concern at Lake Wateree that the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control issued warnings in 2010 against eating more than moderate amounts of some species of fish in Lake Wateree. All told, six species carry warnings: blue catfish, channel catfish, largemouth bass, striped bass, white bass and black crappie, according to DHEC’s website.

Before that, the only other major lake that carried PCB warnings was Hartwell in Anderson County. But PCBs that polluted Hartwell came from an industrial plant, instead of transformer oil, research shows.

Through the years, DHEC has been hesitant to point the finger at a specific source of PCB pollution in Lake Wateree and the Catawba River basin, which extends through Charlotte, North Carolina’s largest city, to central South Carolina.

But a research paper, written by a former DHEC scientist and a colleague, said PCB pollution in Catawba River lakes, as well as in the Yadkin-Pee Dee river basin, was caused, in part, by the “direct application of used transformer oils’’ in mosquito control efforts. Transformer oils contain PCBs. Duke relied at least partially on used transformer oils to fight mosquitoes on lakes it managed along the Catawba River, according to the study.

“We suggest that the culture of mosquito control and malarial eradication that co-evolved with the creation of hydroelectric plants in the early part of the 20th century likely made the use of waste oil from transformers likely, if not inevitable, at some locations in the Carolinas,’’ according to the paper by researchers James B. Glover and Deke T. Gunderson.

Duke, one of the country’s largest electric utilities with more than 8 million customers, launched its mosquito control program in 1923 and ended it in 2016.

Glover, who studied the PCB problem while working at DHEC as an aquatic biologist, said he tied Duke’s mosquito spraying program to PCB pollution through the discovery of a 1970 document from a mosquito control workshop. A Duke official reported the company had relied on used transformer oil, as well as motor oil, in the company’s mosquito control program, he said. A North Carolina health official offered similar comments at the time.

Some 2,500 miles of shoreline in the Carolinas received treatment every eight days, according to Glover’s report, co-authored by retired Pacific University scientist Gunderson.

“The paper from 1970 on the mosquito control program sort of was the smoking gun, where numerous officials mentioned it,’’ Glover said.

Duke’s mosquito control program arose from the creation of lakes in the early 1900s that many feared would be breeding grounds for the biting insects. At the time, malaria carried by mosquitoes was a major concern, and mosquito eradication programs were encouraged in an effort to protect public health, his research shows.

PCBs are long-lasting chemicals that were once used in cooling oil for electric transformers, as well as in paint, resins and carbon paper production, the study said, noting that commercial production began in 1927.

A key allegation in the residents’ lawsuit is that the hazards of PCBs were known in the 1950s and 1960s. But Duke spread PCB-laden transformer oil to kill mosquitoes until at least the late 1970s, the lawsuit says. The material was waste that Duke Energy wanted to dispose of cheaply, the suit says. But the company could have used safer pesticides to kill mosquitoes, the suit says.

“What disappointed me the most is when the PCBs were discovered, they didn’t come forward and take responsibility,’’ Sheheen said of Duke. “There were two things going on. They were trying to control mosquitoes and this was a very cost efficient way for them to get rid of their transformer oil.’’

Duke did some of its own studies on PCBs in the early 1990s, but used a detection limit that was substantially higher than was used by other researchers, which effectively concealed the hazard, the suit said. The study by Glover and Gunderson raised the same question.

The threat of PCB pollution in Lake Wateree surfaced in 1997 amid reports that used transformer oil was dumped or sprayed on the reservoir to fight mosquitoes. At the time, three people who worked summer jobs for Duke Energy in the 1940s said they remembered spreading oil on the lake. One of them said it was transformer oil, The State reported. The area where the material was reportedly applied was at the Beaver Creek bridge area of the lake, The State was told in 1997.

The reports prompted the state Department of Health and Environmental Control to launch an investigation to determine what happened, but it is unclear how the probe turned out. Efforts to gain comment from DHEC this week were unsuccessful. At the time, a Duke spokesman told The State newspaper the company had no records of what mosquito control material was applied to Lake Wateree in the 1940s.

Since that time, however, studies have surfaced showing that PCBs in fish were being found at Lake Wateree.

Lake Wateree was one of 17% of the lakes tested nationally where fish registered PCB levels above a federal safety standard, according to a 2009 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency study.

The study prompted DHEC to test fish in the lake. In 2010, DHEC test results showed some of the lake’s most popular game fish were tainted by PCBs, The State reported in August 2010. Signs were later posted around the lake warning against consumption of more than moderate amounts of certain fish because of PCB pollution.

In addition to the issues at Lake Wateree, the lawsuit also sparked questions about PCB contamination in the Great Pee Dee River basin and in Lake Marion, although that was not the focus of the suit.