‘The most imperiled ecosystem’: Grassland wildlife declining in West Texas, Great Plains

A reflection of the planet’s increasingly volatile climate and the enduring influence of industrial interests, North American grasslands find themselves at the epicenter of one of the most severe biodiversity crises on the planet.

Formerly a vibrant mosaic of life — teeming with migratory birds, diverse fauna herds and formidable predators — the Great Plains and its dwindling wildlife serve as a reminder of the delicate balance essential to sustain ecosystems while also supporting the success of industries necessary for the regional economy and human coexistence.

Data indicates that, in the past century, over 60% of native grasslands, totaling 360 million acres, have vanished. Adding to this, another 125 million acres are at risk in the foreseeable future as warming temperatures create opportunities for expanded agriculture in the Northern Great Plains, while woodland encroaches upon grasslands in the Southern Great Plains.

But the implications extend far beyond land loss, cultivating an even greater concern for native wildlife and the broader ecosystem.

“Temperate grasslands are the most imperiled ecosystem on Earth,” said Kristy Bly, a restoration manager for the World Wildlife Fund’s Northern Great Plains program. “And outside of some recent efforts in our small world, they are overlooked.”

Currently, the Endangered Species Act identifies more than 50 species of prairie wildlife — predominantly native grasses, forbs and insects — as either endangered or threatened. Texas Parks and Wildlife further acknowledges more than 100 rare, endangered or threatened species on the High Plains, many of which do not formally receive federal protections, contradicting decades-long recommendations from conservationists and biologists.

Among those that are widely considered short-listed: the western burrowing owl, monarch butterfly, swift fox and black-tailed prairie dog, a keystone species that now occupies less than 2% of its historic range — a decline attributed to years of intentional poisoning for the purpose of agriculture and development.

Further, the National Audubon Society reports grassland bird populations have plummeted by 60 to 70% since the 1960s, while at the same time, native pollinators face alarming declines due to extensive habitat loss and changing weather patterns — and the ongoing use of neonicotinoid continues to jeopardize their survival.

Already, the black-footed ferret has been extirpated from Texas since the 1980s, and the Great Plains wolf and Plains grizzly bear have long been extinct.

And experts say the crisis is only becoming more dire.

“I think what it really boils down to is the choices of humans,” said Patrick Lendrum, senior science specialist for WWF’s Northern Great Plains program. “Are we going to coexist with wildlife? Where are we going to find space for ourselves and the wildlife around us? It truly is up to us of what that looks like.”

Part One: Silent Plains: With a history of neglect, grasslands have become the forgotten ecosystem

More: Bison decline contributed to dwindling prairie landscape on Great Plains

Human impact and native grasslands

Once home to free-roaming herds of bison and leaping pronghorn, the Great Plains is now a shadow of its former self, embodying the story of disappearing wilderness in North American grasslands.

For decades, agricultural and ranching activities, energy development, and urban expansion have taken precedence over the imperative need for grassland conservation efforts, leading to habitat fragmentation and the near-collapse of a once-thriving landscape.

But most experts attribute the initial impacts to inventions of the Industrial Era that led to the rise in these industries and the removal of bison, one of the region's most ecologically essential species for their crucial role in maintaining the ecosystem through their grazing that facilitated seed and grass dispersion.

“There are three inventions that made it possible for farmers to come out on the Plains,” said Mark Stoll, a professor in Texas Tech’s history department. “The railroad, the classic windmill and barbed wire. After these three inventions? You could say the West was doomed.”

While the rapid decline of bison herds had its roots a century earlier, and the situation worsened as conflict escalated among Plains tribes and European settlers, Stoll said the introduction of the first transcontinental railroad further intensified the issue.

The railroad's construction not only disrupted bison routes, dividing them into northern and southern herds because of their reluctance to cross the tracks, but it also shifted the role of bison into a primary food source for railroad workers. Concurrently, commercial hunters clung to the opportunity afforded by the railroad's accessibility and slaughtered more than a million bison annually.

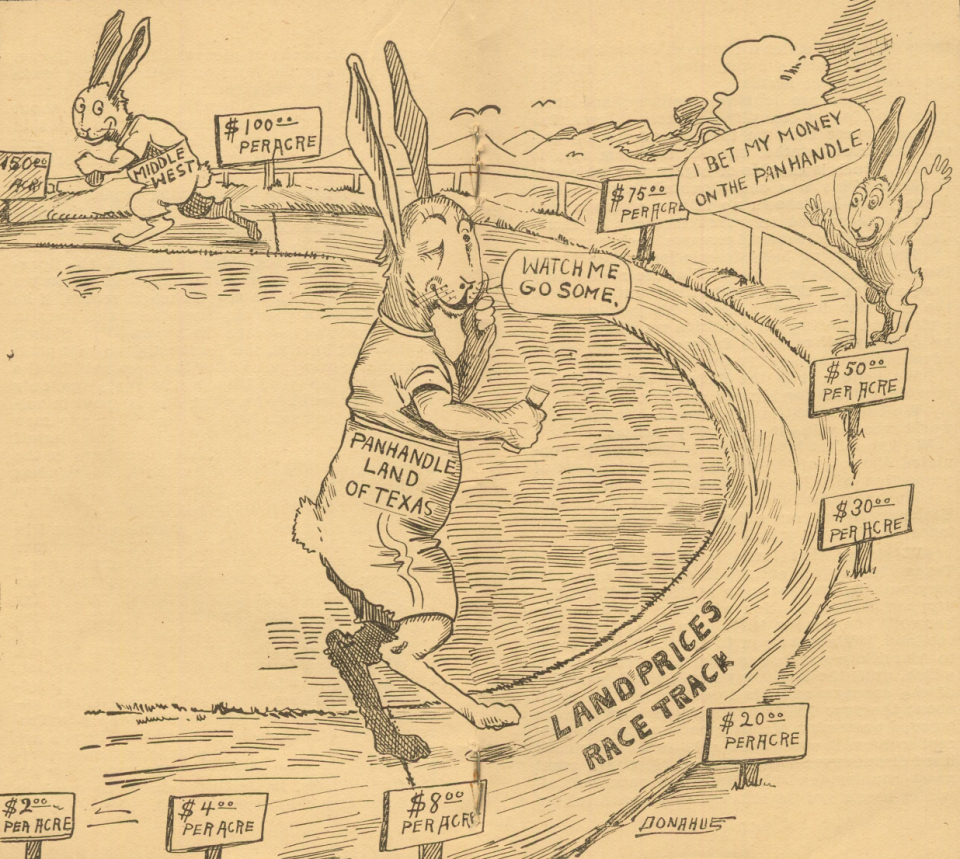

But beyond their impact on bison herds, the railroads played a pivotal role in increasing human settlement, contributing to the expansion of agricultural activities and overall development in the region.

In Texas, an 1854 law agreed that the state provided 16 sections of land — of 640 acres each — per every mile of railroad, according to the Texas State Historical Association, which they later sold to farmers.

In one attempt, a 1915 land promotional — issued by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Company — boasts the profitability of the land and its iconic traits: tillable and rich soil; sufficient slope to curb flooding; watersheds and creeks; and little growth of trees and shrubbery.

“Hence its readiness in adaptability to crops, without delay,” the promotional reads. “It has not infrequently occurred, on account of this very nature of the land, that crops of sufficient abundance have been produced upon the sod of the first year, to pay the purchase price of the land.”

As a result, much of the remaining prairies were rapidly converted into ranches and farms — and little of these claims stand true today.

Russell Martin, who at the time was still serving as the wildlife diversity biologist for Texas Parks and Wildlife, also agreed that traditional agriculture was the most significant driver for the decline of grasslands. And in a paradox of its own making, he stressed the ongoing degradation of grasslands now endangers the very foundation upon which these industries depend.

“The biggest issue is the large expanses of cropland,” Martin said. “When we convert large expanses of areas – entire counties – of pure cropland, then that creates a barrier for animals to be able to move from one grassland area to the next grassland area, because there is effectively a large desert-like area of not suitable habitat. Especially in this part of the world, that conversion from grassland to cropland at a large scale, and in large patches, that is the major driver of the habitat fragmentation, habitat loss and habitat degradation that we’re talking about.”

According to WWF’s most recent Plowprint analysis, which utilized data from 2021, the Great Plains saw more than than 1.6 million acres converted into croplands in 2021 alone. Since 2009, 53 million acres have been converted to cropland. In total, plow-up has overtaken more than 32 million acres of grasslands since 2012, when WWF first began tracking grasslands conversion across the region.

While WWF’s Bly and Lendrum both recognize the crucial role of conservation for the well-being of humanity, they also emphasize the importance of striking a balance between conservation and agriculture, especially in the Great Plains, which provides a sizable portion of the nation’s food and fiber.

“I think a lot of (the public misperception) comes from a lack of connection from people understanding where their food comes from,” Bly said. “I think if there was an appreciation of where their beef comes from, where their corn and soy products come from, where their wheat comes from, then they would want to protect this ecosystem. That connection has been lost over time as we have moved into this urban industrialization era. And I think there is a responsibility to do that — to make those connections again.”

In addition to the consequences met from land conversion, Stoll added that the introduction of barbed wire and perimeter fences to protect crops and cattle also marked a pivotal turning point in the decline of grasslands.

These barriers hindered the mobility of grazers and other migratory species, disrupting historic movement patterns that had persisted for centuries across the plains and posing significant challenges in accessing forage and other necessary resources. As their traditional routes became obstructed, the local landscape saw increased biodiversity loss.

But in more recent years, as agriculture has slowed in the Southern Great Plains, population growth and increased fossil fuel production have further taxed the landscape, causing additional habitat loss for native species, including the lesser prairie-chicken and dunes sagebrush lizard.

At the same time, renewable energy sources are also not without their environmental footprints and can lead to significant habitat fragmentation, said Jon Hayes, who serves as the executive director for Audubon Southwest and vice president for the National Audubon Society.

With the U.S.'s proposed target of transitioning the nation's power to 80% renewable energy by 2030, in an attempt to reduce air pollution, concern of their environmental impact strengthens.

For instance, large-scale solar farms occupy vast spaces of land and leave limited resources available for wildlife. A 2019 study conducted by the Yale Center for Business and the Environment indicates that utility-scale solar development is projected to have a land footprint of 3 million acres by 2030, posing challenges to habitat of thousands of species.

In wind energy, there are (mostly fruitless) concerns about bird collisions, but a more pressing issue, Hayes said, is that turbine maintenance activities can inadvertently introduce invasive plants and shrubs to grasslands during travel, further disrupting the natural ecosystem necessary for native species.

Species at the Heart of Debate

Amid the sweeping landscapes of grasslands, certain species have emerged as focal points in a decades-long debate between industry experts and conservationists. Now, these creatures find themselves entangled in a complex web of interests — and their fate intertwined between economic pursuits and environmental conservation.

The lesser prairie-chicken, for instance, stands as a stark example with its population plummeting by 97% in recent decades. Inhabiting primarily the Permian Basin — the hotbed of the nation's petroleum production — this species has ignited a longstanding battle between conservationists and fossil fuel stakeholders.

Since it was initially proposed for federal listing in 1995, there's been a series of listing and delisting conditions, court mandates and fruitless recovery endeavors. The most recent attempt to overturn the species’ federal protections took place in April when the U.S. House Committee on Natural Resources voted to use the Congressional Review Act to delist the species.

During the April 27 markup, Natural Resources Committee Chairman Bruce Westerman, R-Arkansas, remarked his doubts on the effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act — a belief consistent with much of the Republican party's long-standing criticism of the legislation’s impact on industry and private property rights.

"The Endangered Species Act is an important part of our history, but it's also an outdated part of our history," Westerman said, noting the law was established in the 1970s. "I believe we have an incredible responsibility to steward our rich diversity of wildlife here in America and care for them in ways that allow them to flourish for generations to come. But I disagree with my colleagues when they are adamant that listing a species is the only way to ensure its survival. In fact, we've seen the opposite is often true." (The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service disputed the claim.)

The chairperson cited examples to align with his assertion, including the scenario of the West Coast-based three-inch fish, which, according to Westerman, has received millions of dollars in federal funding but has seen little benefit in species recovery.

He had also pointed out that federal protections of the northern spotted owl have not benefited the survival of the species, which is losing habitat to wildfire. Over the last several decades, wildfires have increased in frequency and severity around the globe. Experts primarily attribute these natural disasters to climate change, which research shows is a direct impact of fossil fuel production.

In May, all 49 Republican senators, including Texas' Sen. John Cornyn and Ted Cruz, supported the resolution to delist the species. U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin III of West Virginia was the sole Democrat to vote in favor, resulting in a Senate vote of 50-48.

A parallel trend emerged in Congress, with a vote of 217-206, in which every affirmative vote for advancing the proposal came from Republicans.

After garnering approval from both, President Joe Biden vetoed the resolution in late September, underscoring the deep-seated divisions surrounding the species’ conservation status.

A White House statement ahead of the decision read: "Overturning common-sense protections for the lesser prairie-chicken would undermine America’s proud wildlife conservation traditions, risk the extinction of a once-abundant American bird, and create uncertainty for landowners and industries who have been working for years to forge the durable, locally led conservation strategies that this rule supports."

Similarly embroiled in controversy is the dunes sagebrush lizard, a species whose need for federal safeguards was identified by conservationists over four decades ago, particularly due to its proximity to West Texas oilfields.

In July, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed federal listing of the species under the Endangered Species Act, and in a swift response, U.S. Rep. August Pfluger, R-San Angelo, introduced the "Limiting Incredulous Zealots Against Restricting Drilling" Act, or the LIZARD Act, which sought to curtail federal oversight, shifting the responsibility for safeguarding the species to individual and industry-led initiatives.

“On the campaign trail, President (Joe) Biden promised to kill the fossil fuel industry, and that’s about the only promise we can count on him keeping," Pfluger stated in the news release announcing the LIZARD Act. "His latest tactic — listing the dunes sagebrush lizard as an endangered species so he can shut down drilling in the Permian — is just the latest in a string of assaults on the Permian Basin and our way of life. The President wants to control private property in Texas. Not on my watch. My legislation protects energy security and jobs in the Permian by nullifying his latest attack."

The species was first proposed for listing in 2010, according to Defenders of Wildlife, but advocates began to cast light on the species' dire situation in the early-1980s.

Located only in the Permian Basin, critics believe the government's hesitance to offer federal protections stems partly from political pressure from fossil fuel interests, which are largely to blame for the lizard's endangerment.

“Like too many other species, this little imperiled lizard found itself in the middle of a very large fight over what should have been reliance on best available science and not pressures from private interests,” Andrew Carter, Director of Conservation Policy for Defenders of Wildlife, said at the time.

Pollinators in Peril

North American prairies are among some of the most intricate and diverse ecosystems on the planet – interconnected by thousands of fauna and flora species. But that number declines as the landscape increasingly battles habitat degradation from human activity.

With hundreds of grass, forb and shrub species, the richness in the landscape’s biodiversity, in a way, has masked the decline of some significant species populations – particularly pollinators – said Vikram Baliga, who is the manager of Texas Tech's Greenhouse and Horticultural Gardens and an assistant professor of practice in plant and soil sciences.

Native bees, beetles, wasps, flies and butterflies serve a crucial role in the Great Plains, where they contribute to the successful cultivation of crops – ranging from vegetables and fruit to fiber. Yet, these pollinators bear some of the greatest pressure from the very industry that depends on their services most.

A recent study in Science Advances stated that pollinator insects have shrunk by 61% due to the “interactive combination of agriculture and climate change,” which have resulted in a decline in habitat of flowering plants and warmer-than-usual temperatures. The use of neonicotinoids also threatens pollinator services and, consequently, native biodiversity.

“A resilient, strong ecosystem has a lot of checks and balances,” Baliga said. “There is so much diversity in our native ecosystems, that the long-term decline (of some native pollinator species) was maybe not noticed as readily, because there were backup species. Think of it as a Jenga tower. You pull a couple blocks, and the tower keeps standing so you don’t really notice. Eventually, you pull the wrong one and the whole thing collapses.”

In the Great Plains, the most notable “backup species,” Baliga said, is the honeybee, which is nonnative and was introduced to the U.S. as, essentially, livestock in the 1600s.

As local habitats shrink due to land conversion, managed honeybees and native bees have less space to interact and acquire resources, yet honeybees have a broader diet and can feed on a wide variety of plants while approximately 20 to 45% of native pollinators, such as bees, rely solely on native flora and specialized host plants.

At the same time, while honeybees are important in the production of numerous crops, they comparatively play a more restricted role in pollinating native plants, and as generalists, could potentially aid in the reproduction and spread of invasive plant species.

Another insect that depends on flowering plant diversity is the monarch butterfly, where the last couple of decades have seen sharp declines in the sizes of overwintering populations in overwintering grounds in central Mexico.

While the precise magnitude of their decline remains a subject of debate, expert opinions range from a concerning 30% to a staggering 90% since the 1990s.

As a candidate species, the future of the iconic species continues to await an official listing from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2024. Yet, even before this official verdict, some conservation organizations have already designated the species as endangered, including the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Regardless of these differing official statuses, there is a widespread consensus among experts: the monarch butterfly remains in jeopardy.

Martin acknowledged that a multitude of factors have contributed to the decline of the monarch butterfly, citing urban development, drought, and the impending climate crisis as significant drivers.

“But what’s really driving their decline is definitely habitat loss and degradation,” Martin previously told the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. “There’s a bunch of stuff that contributed to the (long-term) decline, like the conversion of grassland to agriculture that happened in the Midwest several hundreds of years ago. But in the last 30 years, there’s been more and more herbicide and pesticide use as our farms have become more commercialized.

“And there’s really been a steep decline in the species over the last 20 or so years,” he added.

As the urgency to protect pollinators grows, experts like Baliga are reevaluating the narrative that has surrounded them for the past several decades.

For instance, while the widespread motto to "save the bees" has been a vital call to action, it has inadvertently overshadowed other native pollinator species, each with their unique ecological roles. This skewed focus, Baliga said, has created unforeseen challenges for less spotlighted yet equally essential bees.

“I think the way that we have talked about pollinators over the last 30 years is good in some ways, but it’s also been really detrimental to pollinator health and pollinator biodiversity,” Baliga said. “Because when people say, ‘Save the bees,’ everyone thinks of honeybees. But the fact is, we have dozens of species of native bees, and when you have this narrow host range for something like a little native sweat bee or a squash bee, all those feeding sites are already full of honeybees and that creates a lot of competition. It’s putting pressure on already vulnerable species.

“I don’t think it’s bad that we’ve spent 30 years talking about the honeybees. We have to get people interested, and some of these charismatic fauna and charismatic plants are their door into it and makes them care, and caring is important. I think we just need to be telling the rest of the story,” he added.

Restoring the landscape

Most experts agree that it's not plausible for North American grasslands to ever return to their original state. But their optimism remains in the idea that preserving small patches of prairie can still serve a meaningful purpose, often underestimated by many.

“The problem is that prairies have a PR problem,” Baliga said. “I think if we want to make sure we get to keep experiencing this planet and being a part of this planet, then we have to take some big steps and be aggressive with the way that we alter our own lives. Around here, a lot of that starts with prairie restoration and pollinator management and reduction in pesticide use.”

Plus, as restoration efforts increasingly unfold, he said there are many additional facets to consider — ranging from the impacts of increasing temperatures on native species to the accessibility of seed for historic flora.

Overall, he said he has noticed an upward trend in restoration practices as more of the population begins to recognize the importance of native prairie.

“We’ve done a great job over the last 30 years,” Baliga said. “And we’re making progress.

As a conservationist and rancher in Central Texas, David Hillis, director of the University of Texas' College of Natural Sciences, shared a similar optimism while acknowledging the cultural and economic significance of the agriculture industry, particularly in Texas.

Hillis noted there is a positive trend in the industry as ranches and landholdings begin to recognize the significance of grasslands and shift toward more sustainable practices.

“We’re actually turning the corner and are making some progress on bringing grasslands back,” Hillis said. “They’re critical for lots of reasons. They’re important for biodiversity. They’re important for water filtration. They recharge our aquifers. They’re important for carbon storage and carbon sequestrations. There are just lots and lots of reasons why grasslands are critical. And we have hammered grasslands enormously in the last 100 years, so now the question is: What’s the future hold?”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has also increased emphasis on sustainable agriculture, encouraging farmers and ranchers to promote environmental stewardship through a range of conservation practices, including integrated pest management, crop diversity, agroforestry — which can serve as windbreaks and buffer strips for native pollinators — and several soil conservation methods, including strip cropping, reduced tillage and no-till.

Hillis added that rotational grazing of cattle — now the region's primary grazers — is also essential for maintaining the health of prairie ecosystems by preventing overgrowth and promoting biodiversity, which in turn, can provide habitat and sustenance for a portfolio of wildlife from small insects to large mammals. A recent study by the USDA Economic Reserve Service revealed that 49% of ranchers and cattle producers in the Northern Plains and Western Corn Belt and 25% in the Southern Plains have already adopted rotational grazing.

Additionally, many in the industry believe the practice of regenerative agriculture, which emphasizes crop rotation and reduced ploughing, is the solution that will promote a paradigm shift. Though the concept has become riddled in controversy among scientists in recent years, due to its failure to prove itself a long-term solution for soil carbon capture, it does serve other ecological benefits, including land preservation and reduced water usage.

“It’s not all hopeless,” Hillis said. “I think there is a lot of potential for bringing grasslands back. People are now aware of the importance of grasslands and the beauty of grasslands. So, I do think there’s some hope for the future.”

Echoing a similar sentiment, Bly and Lendrum also shared a message of hope.

Through WWF’s initiatives alone, they aim to conserve a minimum of 100,000 acres of native grasslands and restore at least 150,000 acres of degraded habitat to ensure the preservation and connectivity of these vital prairie lands.

Already, they have seen progress in their efforts.

Not only are they hopeful in the work they pursue in WWF’s Northern Great Plains Program, but they highlight the important roles of other organizations that value the importance of U.S. prairies and grasslands, such as Defenders of Wildlife, the Center for Biological Diversity and Audubon.

“There are already a lot of great stewards of the land out there that have enabled the return of species,” Lendrum said. “But we have to recognize that the Great Plains will never be the American Serengeti that it was.”

This story is part of the ongoing 'Silent Plains' series by the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal on the disappearance of grasslands and the long-term implications of biodiversity loss and wildlife loss in West Texas and the broader Great Plains.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: ‘The most imperiled ecosystem’: Great Plains grassland wildlife declining