‘We knew that she would have a bright future.’ Why are so many babies dying in Ohio?

Amelia Robinson is the Columbus Dispatch's opinion and community engagement editor. She is a lifelong Ohioan. @1AmeliaRobinson

A grief she never saw coming found a home deep within Seneca Bing's heart.

And for a very long time after her healthy 10-month-old daughter Aliyah Danyell Bing died in 2015 from what was determined to be a sudden unexpected infant death, the notion of babies caused Seneca great agony.

"I did not want to talk about babies, see babies, know about babies," the Gahanna resident told me. "I didn't want to go down the baby aisle."

Seneca said she believes she and her baby received good care, but she knows that is not the case in many situations. She is finding ways to use the tragedy that visited her family for the good of others.

It is a horror that is too common in Ohio — particularly when it comes to Black babies like Aliyah.

Black babies accounted for 63% of infant death in Franklin County the first quarter of 2023, but only 34% of births, according to the city of Columbus' infant mortality report.

Nearly seven Ohio babies die for every 1,000 live births.

Statewide, Non-Hispanic Black babies like Aliyah are nearly three times more likely to die before their first birthday than non-Hispanic white infants, according to the Ohio Department of Health's 2020 Infant Mortality Report.

Solutions to this Ohio sorrow deserve more attention, action and financing from policymakers and other leaders.

There has been progress.

Groups like CelebrateOne here in Columbus are working on the local level around the state to find a solution.

Gov. Mike DeWine in January announced the Ohio Department of Medicaid's new Comprehensive Maternal Care program. The statewide, community-based initiative aims to improve the health of mothers, babies and family members covered by Medicaid.

How can we lower infant mortality rates? The alarming number of Black baby deaths here must be stopped

There are 127 recommendations related to housing, transportation, education and employment in the 2017 report "A New Approach to Reduce Infant Mortality and Achieve Equity" which was signed into Ohio law after a bipartisan push.

There is still much work to be done in housing, transportation, education and employment.

Only 17% of the recommendations have been implemented. There has been various levels of progress in only 44% of the recommendations still not implemented.

Why is infant mortality so high in Ohio?

This state — the nation's seventh largest by population — ranks a dismal 41st out of the nation's 50 states when it comes infant mortality, according to the Health Policy Institute's 2023 Health Value Dashboard.

The disproportionate impact on Black babies is staggering.

Painfully, 864 Ohio infants died before their first birthday in 2020. Of those, 493 were white and 326 were Black.

From 2018 to 2020 the March of Dimes says 72.2% of the state's live births were white, 17.5% were Black, 5.7% were Hispanic, 3.4% were Asian/Pacific Islander and 0.1% were American Indian or indigenous to Alaska.

Fatherhood matters: Columbus must debunk myths about fatherhood

This is not only an "Ohio" problem, this is a Columbus problem.

Babies are dying in the Columbus area, the state's most economically prosperous community. As with the rest of the state, it is even worse with Black babies.

In Franklin County, the infant mortality rate for Black babies has risen from just over twice that of white babies in 2014 to nearly triple that of white babies in 2021.

The leading causes of infant mortality are poor birth outcomes; accidents, injuries or violence and unexplained infant death as was in the case with Aliyah.

Health Policy Institute of Ohio's newly released "action guide" highlights policy options for addressing racism which has been identified as a social driver of infant mortality in Ohio.

The guide says:

Racism impacts community conditions including access to housing, transportation, healthy food and quality education. These conditions, in turn, make it more difficult for people to live healthy lives.

Racism is a form of trauma. Exposure to racism and the resulting community conditions can cause toxic stress, resulting in both physical and mental health challenges.

Racism can impact the treatment that individuals receive from healthcare providers through both implicit and explicit bias.

The truth of infant mortality: A life behind every statistic

The statistics are part of the story, but they can only go so far in relaying the truth of infant mortality.

Each number represents an extinguished spark of life.

These babies aren't just statistics.

Their deaths are hope stopped in its tracks.

Their deaths are heartbreak.

As with many of those deaths, Aliyah's passing was a tragedy that seemingly came out of nowhere without a true explanation.

Aside from race, Seneca Bing says she and her husband Carlos are not likely the couple one imagines when they think about Ohio's infant mortality crisis.

"You hear a lot about the social determinants of health," Seneca told me. "You hear about the disparities and how people are (not) treated (right) in the hospital. None of that was my experience."

Racism disparities can't be ignored: Time to recognize role of racism in infant mortality

Aliyah had just had a great checkup. Seneca says the doctor told her that her daughter was healthy. All indications were that Aliyah was just that.

She was blossoming and had already made a deep impression on her siblings — a 10-year-old brother — Seneca and her husband's first child together — and an older brother and sister from her father's prior relationship.

'Trails of love that will carry on for years to come'

The couple had high hopes for their daughter achieving her heart's desire. Anything she wanted.

They had already put together her Ohio 529 College Savings Plan and were in the process of getting life insurance for their growing child.

"I wanted her to explore whatever she loved. We would have nurtured whatever it was," Seneca said. "If it was art she loved, we would have nurtured that. If it was science, we would have nurtured that. We knew that she would have a bright future."

Nicknamed Lee-Lee, Aliyah was bubbly, often laughing and was crawling on the verge of walking, her mom says.

The baby's obituary reads:

When you held this 10-month-old, you instantly felt her loving and rambunctious spirit, coupled with those big brown eyes and a smile that would melt your heart. Lee-Lee had a personality, all her own, that far exceeded her tender age. She loved to cuddle with her big sister, and to laugh and play with her big brothers. If you weren't watching her, she would hit and kick you all in one motion. In Aliyah's short life, she left trails of love that will carry on for years to come.

"I always wanted a girl and a boy," Seneca told me.

Aliyah was the girl her mom — a former school counselor who now serves as Columbus City Schools' interim director of family and community engagement — long wanted.

"I dropped her off at her babysitter. (She) went to sleep and an hour later they were calling, and she was unresponsive," Seneca said.

For a week, the Bings and their family were at Nationwide Children's Hospital with Aliyah. The Ronald McDonald House Columbus put up some relatives.

"You want to hope things are getting better," she told me. "But at a certain point, we had to face the reality that it was not and that there were some decisions that we had to make as a family."

The thought of babies brought agony to Seneca after her daughter's death, but she turned a corner and started sharing her family's story.

"One of the things that people tend to do is suppress their feelings. They don't want to talk about it — especially Black women. We don't talk about a lot of anything. We keep it internal — men too — but you have to talk. You have to experience the emotions you have to allow yourself to do that."

In 2020, Seneca, a certified grief educator, founded RiseTogether which aims to provide resources and support to families that have lost children and siblings.

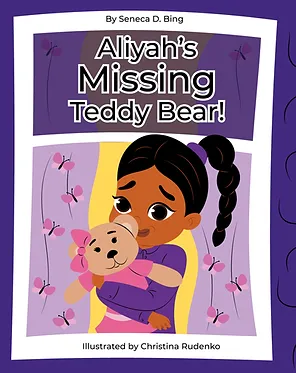

She penned a coloring book and a children's book called "Aliyah's Missing Teddy Bear" which touches on grief and emotions as well as the activity book "The Positive Perspectives."

Bing and her husband co-authored the journal "Finding the Light Within."

From her work with students and families, Seneca says she knows many mothers and babies face disparities in health care that often lead to tragedy. She also knows this from what she witnessed when she was in the hospital with her daughter.

Seneca recalled a young mother from the Atlanta area who brought her child to Nationwide after experiencing difficulties at a hospital close to her home.

She is working on a program to provide care packages for families in similar situations.

The Bings were showered with love and food the week leading up to their gut-wrenching decision to remove Aliyah from life support.

"They were feeding the whole hospital," Seneca recalled. "A lot of people don't have that because some of the people that came to eat didn't have anyone else with them. They didn't have any family members."

She says she finds joy in the memories of her daughter and see her through other children.

"There's a little girl at my church that is (Aliyah's) exact age," Seneca said. "I'm able to see her growth as how it would be if (Aliyah) were here."

Amelia Robinson is the Columbus Dispatch's opinion and community engagement editor. She is a life-long Ohioan. @1AmeliaRobinson

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Babies are dying in Columbus. Why is Ohio infant mortality so high?