How 'the most violent' special education school ended restraint and seclusion

This story was produced by the Teacher Project, an education reporting fellowship at Columbia Journalism School.

BETHLEHEM, Pa. – Twenty years ago, a visitor to Centennial School would have heard a cacophony.

“Banging on doors, yelling, wailing,” said Julie Fogt, the current director of the school. “Adults were loud: ‘Stop that, stop that! Crisis! I need help!’”

It was a private school, but public schools paid to send their most troubled kids there. The school took only children who had both a diagnosis of autism or emotional disturbance and a history of severe behavior issues.

“It was the most violent school I’d ever been in,” said Michael George, the former director.

A man with blue eyes and a bushy white mustache, George stepped into the role of director in 1999. The year before, a population of only around 80 kids were physically restrained over 1,000 times. Students were dragged, kicking and screaming, to locked seclusion rooms. Most of the school’s furniture was old and dilapidated. As one administrator told George, why bother purchasing something new when an angry kid would probably break it the next day?

George and the school’s teachers realized the physical restraints were making student behavior worse. So they made it their mission to change the school’s culture. In 1999, Centennial went from 233 restraints in the first 40 days of school to just one restraint in the last 40 days of school. Within four years, restraints were down to zero. The school also saved money, according to a 2005 study, because it didn’t have to hire a huge crisis staff anymore.

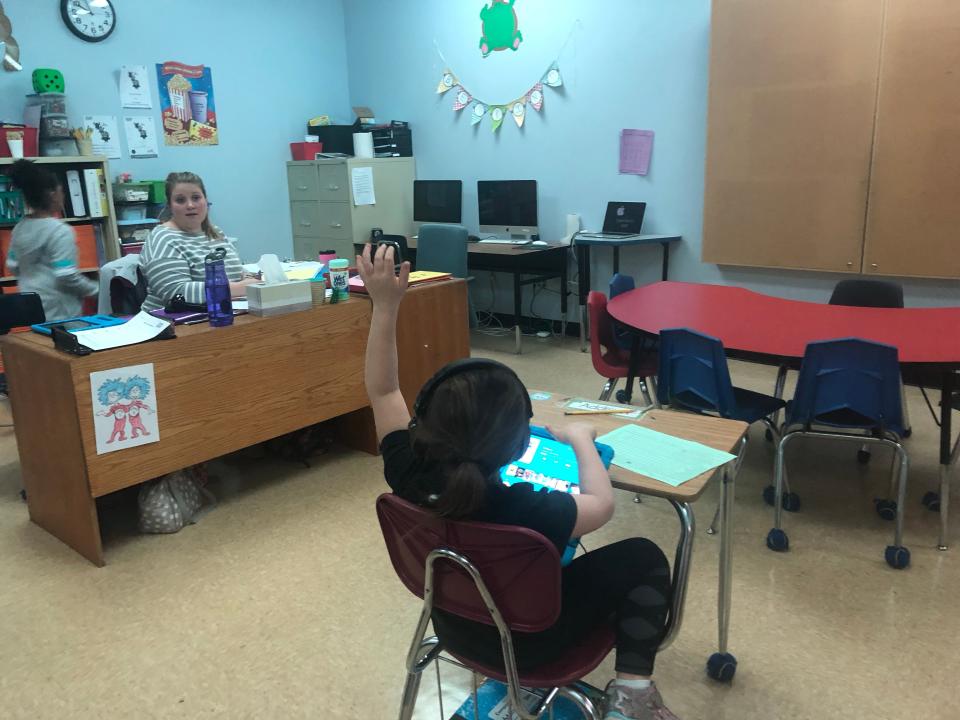

During a visit to the school last year, the only noise was the murmur of kids chatting and teachers praising their work. The school is clean, with halls that smell like peppermint. Some classrooms have gentle blue overhead lights, for kids with light sensitivity. It feels like a zen spa for kindergarteners.

Centennial’s success, teachers believe, proves that restraint and seclusion is almost never necessary, even for kids struggling with the most serious behavior issues.

That belief stands in contrast with national trends. According to the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights, 75% of all restraint and seclusion incidents in public schools happen to kids with disabilities. Data on restraint for private special education schools is much more scarce, but some states show disturbing trends. In California, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Maryland, and Rhode Island, between 45% and 67% of all restraint and seclusion incidents in the entire state take place in private special ed schools -- often schools where students are enrolled at taxpayer expense.

Investigation: Private special ed schools can restrain kids with disabilities 1,000s of times. Parents might not know.

"We’re taking a vulnerable population and making them worse, using taxpayer dollars,” George said.

Leaders from private schools that do use restraint and seclusion sometimes say there are few other ways to deal with severe emotional outbursts. They ask how they're supposed to react if a child tries to punch another child, or bang their head over and over against a wall, or flip over a table. Schools like Centennial admit it's hard, but they say their own experience proves it can be done.

"We have the same environment, same students, same teachers,” Fogt said. “Different approach. "

A positive approach

When Bryce Adair was in fifth grade, school was a series of constant meltdowns. As someone with autism, he was easily overwhelmed by anxiety when there were too many people or when a lesson was too difficult.

“I used to crawl under my desk and curl up into a ball, and I would just cry,” he said.

When his public school referred him to Centennial, one of 37 private schools approved to take special education students in the state, he blossomed. He stayed at the school from sixth to 10th grade, until he was able to transition back to public school. Now 18, Adair graduated from high school this spring and has started a career in electronics.

His success stems from the changes the school started to make in 1999. To radically reduce restraints, Centennial didn’t do anything particularly radical. It used techniques that were already well-supported in research.

The main technique the school used is known as Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports, or PBIS. In short, teachers focus less on punishing bad behavior and more on teaching kids what good behavior looks like. The school adopts three to five overarching behavioral expectations for the entire school, like “Be responsible” and “Be respectful.”

Teachers are trained to look for when kids are doing something right, not something wrong, and reward them with praise and points. Centennial shut down the seclusion room and turned it into a school store, where kids trade points for prizes. Kids can’t lose any points on their point sheet, only earn them. This is so students always feel like they have something to gain from behaving well.

Centennial had tried stuff like points sheets before, but the school’s efforts were disorganized and scattershot. For the techniques to work this time, the school needed a structural and cultural overhaul. Classes would now be led by two teachers, including a more-experienced lead teacher. Teachers got at least three hours of professional development a week. Anything that worked in one classroom would then be codified into official school policy so everyone would be doing the same thing.

“[Bryce] had consistent expectations that were the same in every room, with every teacher,” said his mom, Kim Adair.

All this talk of praise and positivity may make it seem like the school coddles its students. But expectations are high. At Bryce Adair’s old school, if he wanted to get out of class, all he had to do was throw a fit and the staff would call his mother to come pick him up. That didn't work at Centennial.

“Once I realized that they weren’t going to be lenient and they upheld their rules, I hated it," Adair said. “The first year was really rough. I was not really taking to it well. I flipped a table. I threw a desk.”

After a crisis, students must create an "action plan" to make sure they make up for any learning they lost. If they rip up a piece of paper, for example, they have to spend points to buy more paper from the school store. If they miss class because of a tantrum, they'll make up their work during break time.

Eventually, Adair realized, “You are responsible for your own actions and you have to do your work. Because if you don’t, it will sit there and stare back at you as long as you don’t do it.”

Parents, counselors and teachers can all be involved in “problem-solving sessions” if the student continuously acts out. Adair’s mom was on the phone with teachers weekly.

While teachers were strict, Adair said, they were also kind. He remembers sharing jokes with one of his favorite teachers, Emily Polefka, and watching Bob Ross painting videos together during break time. He began to behave better, not out of fear of punishment, but because he cared about what his peers and teachers thought about him.

"Once you start to know them, you don’t want to be making trouble for teachers either because you have a relationship," he said.

Polefka now works as a special education teacher at a public school. She said she still often thinks about Centennial's motto: "Nice matters." It means “being nice to kids, treating each day as it’s a clean slate,” she said. “Respecting them and being kind to them, even when it feels almost impossible to be kind because you're so tired or stressed or overwhelmed with the situation you're dealing with."

Success in other schools

The approach has spread beyond Centennial.

At Grafton, a private behavioral health network in Virginia that runs psychiatric facilities and private therapeutic schools, staff physically restrained adults and children with disabilities more than 6,000 times in 2003. So many employees were injured, the company couldn’t even get worker’s compensation insurance.

"Emotionally, it’s hard. Because no one wants to do that,” former aide Kim Sanders recalled of restraining a child.

Using input from teachers, Sanders helped Grafton develop a system for how to de-escalate most crisis situations. Now, if de-escalation does not work, staff members can use foam mats as shields instead of putting their hands on a student. Between 2003 and 2016, restraints went down 99%, including a drop of over 40% in the first year alone. The company also saved $16 million because there were fewer staff injuries and lower turnover.

One school that decided from the beginning to avoid restraint and seclusion is Port View Preparatory, a private special education school in California. Administrators said the school, which serves students with emotional disorders, has never used restraints or seclusion since it opened in 2014, beyond briefly holding a child's hand if they were trying to hit themselves.

The key is looking at it "from a relationship perspective," said co-founder and co-principal Edward Miguel. "When a restraint is not an option, and you have a conviction about that, you develop into different aspects of the relationship. It’s based on trust.”

Miguel pointed out that schools like his usually create behavior plans for children who have acted out in the past. That makes him question why schools would have to resort to "emergency interventions" like restraint and seclusion, when they could plan alternative responses in advance.

“If I know those behaviors exist, how is it an emergency?” Miguel said.

‘What if they try and hurt themselves?’

Officials at Centennial say the biggest challenge when they tried to reduce restraints wasn’t changing the students’ behavior and attitudes. It was changing the adults’. Staff members were afraid if they stopped restraining kids, they would get hurt. It was a well-founded fear – in one school year, there were 30 assaults against staff. Some staff members thought that students' behavior was beyond their control: their disabilities were too severe, or that their home life was too traumatic and neglectful.

“I would hear one excuse after another,” George said. “But the one thing I never heard … was that we could do things better. That maybe we owned some of this violence that was occurring, because of the methods we were using.”

Now, even when a child is aggressive, throwing rocks or knocking over chairs, teachers won’t escalate. Staff will take every other student out of the room, stay at a safe distance so no one gets hurt, and wait for the child’s rage to blow over.

Remaining calm in that kind of situation is scary and hard. Emily Polefka, Bryce Adair’s former teacher, was a young graduate student in her first year of teaching when she joined Centennial in 2016. She remembers having no idea what to do when she saw a student react in anger and kick something – she just froze.

“What if they start hurting someone? What if they try and hurt themselves?" she thought.

But the lead teacher kept calm, quietly walked up to the boy and gave him a direction. He trusted her enough to cool down.

“She was patient with the student and didn’t make a big deal of it,” said Polefka. “I think a lot of times we encourage our students to keep our problems small, and I felt her keep that problem small.”

Centennial had to close in March because of the coronavirus pandemic, but it didn't stop teaching its students. It created a detailed distance learning plan so teachers still met with students daily, and kids who didn't have computers at home got devices on loan. The school plans to reopen in September.

"I hope to see you all real soon," Fogt told her school in a video message in March. "And just remember – now more than ever, nice matters."

Contributing: Joseph Hong, The Desert Sun

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Disability in kids: Private special education school without restraint