Mothers and advocates call for more education around perinatal mental health in the Yukon

When Kylie Campbell-Clarke became pregnant with her first baby a year and a half ago, she didn't expect the system to be in what she describes as such a state of failure that it would result in deciding that Maverick would be her one and only child.

"The solution to my poor mental health was ... you'll have the baby, and you'll be fine," Campbell-Clarke said, as she described her difficult pregnancy dealing with depression and anxiety after she went through a miscarriage.

"I should have been seen by the psychiatrist from the get-go. But instead, I didn't get that until four months postpartum. When you're giving birth, the hospital should have someone there counselling you, going like, 'How are you doing?' As soon as the baby's born, they kind of check all the incisions, but they don't check on you as a human being."

Campbell-Clarke says not once was she asked about her mental health during or after her pregnancy — she was left advocating for herself.

Her experience echoes that of other women in the Yukon. According to the results of a recent survey by Postpartum Support Yukon, one-third of women say they were never asked about their mental health during or after their pregnancy.

Kylie Campbell-Clarke, seen here with her nine-month-old son Maverick, went through a long period of perinatal depression and anxiety. "I think I'm doing well now," she says. (Kylie Campbell-Clarke )

The online survey, conducted between August 2022 to March 2023, had 28 responses: almost all participants live in Whitehorse, with 68 per cent between the ages of 25 and 34 and 32 per cent between 35 and 44.

Shanny Kaiser, the founder of Postpartum Support Yukon and author of the survey, said the survey is quite informal but goes to show how society often romanticizes parenthood, making it hard for those with a different experience to come forward.

She said in addition to stigma, there's a lack of education surrounding perinatal mental health — which covers the period from conception through the first year after birth — in the Yukon. Her organisation is calling on the territorial government to create a public health campaign on the issue.

"Commonly, we hear 'postpartum depression' ... but it actually can arise at any point," Kaiser said.

"The effects are rippling. If it's not treated, if it's not caught, the birthing parent can continue to experience that for years. And we see it impacts partners, and then we see it also in the children in terms of their behaviour and cognitive development."

Challenge of living in the north

While Statistics Canada doesn't include data from the northern territories, including the Yukon, its last report showed 23 per cent of Canadian women who had recently given birth had feelings consistent with postpartum depression and/or anxiety.

Meanwhile, Postpartum Support Yukon estimates that an average of 91 Yukon mothers experience perinatal or postpartum mood and anxiety disorder each year.

"I think all of us by virtue of living in the north (are at risk)," Jo Lukawitski, who works with Partners for Children — an organization that supports Yukon families and young children — said.

"It's a geographically isolated location and the loneliness that can happen after having a baby, it gets magnified."

Lukawitski said people with a history of any kind of mood disorders are at higher risk to struggle mentally during or after a pregnancy. New parents, she added, sometimes have trouble recognizing that they are mentally struggling.

"We often think it's just sadness, but there's lots of emotions and different symptoms that can come up for both parents," Lukawitski said.

"There can be feelings of guilt and shame, or even hopelessness ... feelings of rage. Sometimes there's unwanted thoughts."

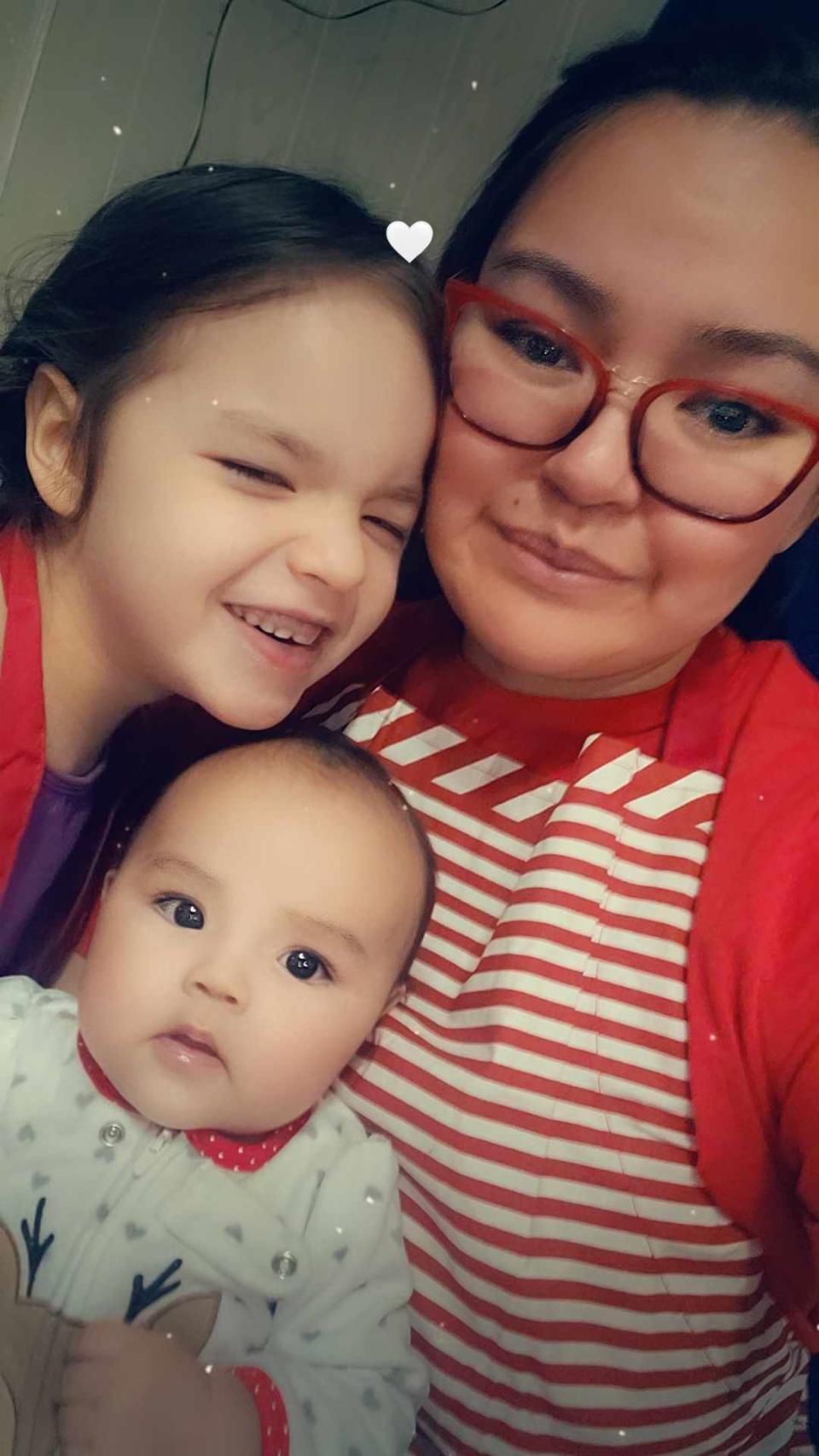

Megan Ladue, seen here with two of her three children, says she moved from Ross River to Whitehorse in part to have better access to services related to perinatal mental health. (Megan Ladue)

Megan Ladue, a mother of three from Ross River, Yukon, experienced just that.

She said she ended up twice in the hospital over mental health issues after giving birth.

"After my second daughter was born, I had a little bit of a postpartum depression," Ladue said. "It was pretty bad. I felt like I wasn't doing stuff the right way — it was really hard on me."

Ladue decries the lack of support in the small community of Ross River and said she wishes healthcare providers would have asked more questions about her mental health, or offered in-depth conversations on the subject.

"You know when you see in the movies ... these perfect little families ... I wanted that," she said. "But with my two other older kids, I didn't have that. My family was broken. And I just was depressed ... Now I'm happy and I have a great partner who's very supportive. I know there's other women that go through this."