Some mountain residents still snowbound. 'They must have forgotten about me'

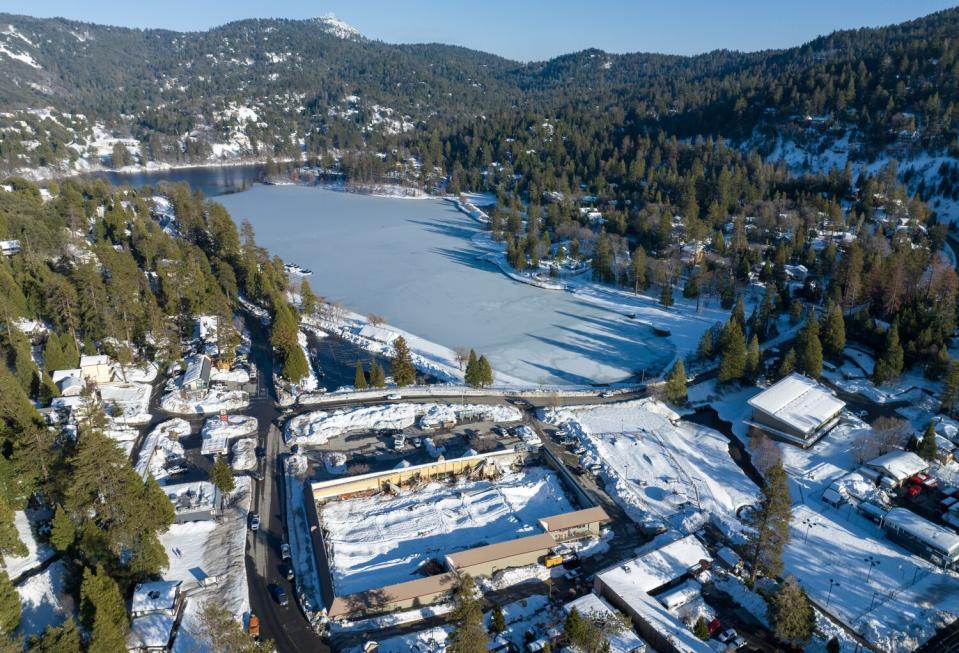

The snow is melting in the San Bernardino Mountains after eight to 12 feet of powder fell in back-to-back winter storms last month.

Damaged homes dot the landscape, and the storms will have an economic ripple effect on the mountain communities that will continue long after the snow is gone, according to mutual aid groups, which point out that — weeks after the worst weather — people are still trying to refill depleted pantries and remain in need of other resources.

San Bernardino County plans to wind down a food distribution center in the hard-hit Crestline community by the end of the month, and the Red Cross will close its shelters for people displaced by the storms on a similar schedule.

Established mutual aid groups and citizen volunteer groups that formed during the storms believe the area's long-term recovery needs to involve community-led efforts, much like those driven by residents who banded together when county and state agencies were slow to respond amid the crisis.

“You don't just get your road plowed and then you get your car out and then things are OK. There's so many things you have to deal with afterward,” said Dawn Wisner Johnson, a volunteer with the grassroots organization Operation Mountain Strong.

Material goods can be replaced, Johnson said, but after weeks of being trapped in their homes by several feet of snow — often facing fear and desperation — people will need to work through the trauma, which will linger like a bruise.

On a recent overcast afternoon in March, 60-year-old Johnson was at Northpark Baptist Church in San Bernardino, trying to help a Crestline woman find a pair of shoes. The woman also needed a new roof; hers collapsed in the storms. County officials said there were currently 68 homes that had been red-tagged, meaning they are unlivable, and 196 have received some type of structural damage.

Members of citizen volunteer groups who spoke with The Times said they never wanted to be caught off-guard again. They want to organize and prepare for whatever comes next, like possible landslides or floods.

“I want the world to know that we're in this for the long haul, and probably for the next disaster," Johnson said of Operation Mountain Strong, "because we've learned so much through this.”

Johnson and other volunteers at the church continue to fill grocery bags with canned food, bread and other goods even though the main highways to the mountains have been cleared.

Two of the three markets in the San Bernardino Mountains remain closed after they were damaged during the storms.

Volunteer groups including Operation Mountain Strong and Mountain Area Mutual Aid continue to direct residents to donation distribution centers in Crestline and at the Blue Jay Cinema near Lake Arrowhead.

“People still need help and still see us as a lifeline,” volunteer Patrice Mock said from inside the movie theater, which has been converted into a citizen-operated distribution center. “Residents come here and tell us about being trapped and how their neighbors helped them with food, but after a few weeks of being trapped, their pantries run low.”

Her daughters Faith Mattioli, 32, and Hope Mock, 23, have been working out of the theater since the beginning of the month along with their father, Wrex Mock, the theater manager.

Theater employee Kristen Epp, 19, recently moved to the mountains and didn’t know what to do after being snowed in. When Mock, her manager, asked if she wanted to help, she felt like she couldn’t pass up the opportunity.

“I felt kind of bad just sitting around," Epp said."I was looking on Facebook for anybody needing help, they were always too far away.”

In news segments about the mountain communities, the narrative seems to be about normalcy returning as the snow melts away, Epp said.

“A lot of this mountain is elderly and they couldn’t shovel their cars out. People are still stuck now,” Epp said, shaking her head in disbelief. “People are still hurting, who are out of work and living paycheck to paycheck.”

The county opened pop-up assistance centers for the first time in Crestline and Running Springs on Saturday and Sunday, where — among other assistance — residents could get help filling out insurance claims or other paperwork related to the damage caused by the snow.

There is currently no process for residents to file federal disaster claims, according to county spokesperson David Wert. And, he said, local government agencies seldom have funding available to provide assistance with homes damaged in a disaster. But for homeowners, the county will waive up to $5,000 in planning and building fees, and $3,000 and $15,000 grants are being offered for businesses impacted by the storms.

Officials claim that the pop-up centers have helped more than 1,700 people with food, water and other household supplies. The Red Cross said it provided 370 overnight stays to more than 80 residents at three emergency shelters.

Meanwhile, the self-reliant residents of the mountain communities have worked to help their neighbors.

After the roof collapsed at the only market in Crestline, 30-year-old Max Von Strawn grabbed whatever extra cans of food he could find in his pantry and set up a pop-up tent outside Goodwin and Son’s Market.

“I just said this is open for donations,” Mountain Area Mutual Aid volunteer Von Strawn said. “And it just took off from there.”

Although the mutual aid group was formed before the storms, it took on an active role in food distribution.

For weeks, Von Strawn helped distribute food. Phone numbers were passed around in group chats or on Facebook with people who needed help and those who had shovels, groceries or firewood. Strangers called Von Strawn, and he did his best to connect people.

“I’m grateful people saw the need and helped out,” he said. “There’s still a need for help.”

Help has poured in from across the country, like the heavy equipment brought in by the Discovery Channel stars of "Diesel Brothers." Nonprofits CalDart and Texas-based Operation Airdrop flew supplies up to the mountain when the roads were closed. The nonprofit Cajun Navy Ground Force also assisted Operation Mountain Strong in digging people out of the snow and moving supplies across the mountains. And World Central Kitchen distributed 56,000 pounds of produce and 1,600 hot meals in the San Bernardino Mountains, according to the nonprofit.

Lauren Kruz, 39, with the Mountain Provisions Cooperative, is operating the Free Store in Cedar Glen, another distribution stop for residents who need produce, coats and other supplies.

Kruz and Gavin Bialecki planned to launch a food cooperative when the storms hit the mountains and closed the local grocery stores.

“We got a bunch of food donations from people on the mountain, off the mountain,” Kruz said. “We really just wanted to mobilize everybody that we could to bring resources up here for our community.”

The group partnered with Operation Mountain Strong to distribute food, but there was the problem of figuring out where people were stuck.

In late February, Kristy Baltezore put together — with the help of a person who works as a data systems manager — a self-reporting system on Google Docs for people to say whether they were snowed in and in need of aid. Geotags within the system would provide accurate location data.

Some residents filled out the form. But in the mountain communities, it’s typical even when there are no storms for the Wi-Fi to go out and for people to lose contact with the world. So a number of relatives and friends of residents, some of whom are elderly, found the form on social media and filled it out.

Within the first 48 hours of launching, they had information on more than 400 local households, and that grew to 600 by the time volunteers handed over the information to fire and rescue personnel, Baltezore said.

Initially, she could not get emergency officials to take the data, even though it was a source of real-time information in the difficult days after the storms passed.

“It was frustrating to me that nobody seemed to understand how essential it was to have a geotag to know where an elderly person was or to know where your chemo patient was staying,” Baltezore said.

Because the snow was piled so high, houses and their addresses were almost completely obscured, making finding residents an arduous task, according to volunteers who delivered goods.

Before the storms, Operation Mountain Strong volunteer Lisa Griggs didn’t know many of the mutual aid groups she has come to work with over the last month. She's found herself digging people out of their homes and delivering goods across the mountains.

“I've met the most amazing people that I've ever met through this disaster," said Griggs, a local entrepreneur. "I think beautiful things can be birthed from that.”

But there is also fighting among the volunteer groups.

Members cannot agree on what shape long-term recovery should take.

Griggs, 49, said there was a dispute over who would claim $60,000 raised in a GoFundMe campaign that was meant to aid in disaster relief. The campaign was organized by the Mountain Provisions Cooperative, but members of Operation Mountain Strong say the money was meant for their cause.

“The co-op doesn’t want to hand over the money. They want us to present it to their board and jump through all these hoops,” Griggs said. “It just never was supposed to be that way.”

Baltezore, 44, claims that members with Operation Mountain Strong have accused members of the cooperative of stealing the money. She has since distanced herself from Operation Mountain Strong because of the fighting and accusations.

“The GoFundMe always said that it was for community rebuilding funds in partnership with Operation Mountain Strong and other entities,” Baltezore said.

The goal is for the cooperative and the other mutual aid groups to find a legal entity to receive the money and distribute it, according to Baltezore.

Disagreements over money aside, people are still in need of help. More snow was in the forecast for Wednesday for the San Bernardino Mountains, according to the National Weather Service. Volunteers continue to find residents snowed in from the last set of storms.

Rita Nelson, an Operation Mountain Strong volunteer, visited an older woman in a damaged mobile home on March 23. The woman spoke softly to Nelson, a stranger, when asked if she was in need of anything.

“Maybe some toilet paper,” 70-year-old Virginia Hauser said from inside her home in the Valley of Enchantment Mobile Home Community.

Nearly a month after the massive snowfall, Hauser remained in her home. Her porch had buckled under the extreme weight of the snow, and a large crack cut across her living room ceiling.

Hauser, who said she was unsure how to document the damage for a disaster relief claim, didn't want to stay in a shelter. She said she needed to stay with her 11 cats.

She claimed a firefighter agreed to let her stay if she promised to avoid any of the damaged rooms in her home. And, she said, someone promised to pick her up days after the storms hit.

“But they must have forgotten about me,” Hauser said. Still, she said, “my neighbors check in on me, bring me food."

There are more residents like Hauser, unsure where to look for help or whom to speak to about home repair.

All Nelson could offer Hauser was some cat food and some groceries. She promised to return with help.

As she walked back to her car, Nelson messaged other volunteers to look for cat foster homes and a place for Hauser.

It was the first of many homes Nelson visited in the neighborhood on an overcast March morning. While she was surrounded by people in need, Nelson did not let on that her own home in Running Springs was damaged in the storm and now unlivable.

“I can’t go back home. I have to clear out all my stuff,” Nelson said in her car.

As a traveling public notary, Nelson had not been able to work since the storms hit.

She and her 13-year-old daughter were displaced after their roof was damaged and the power was knocked out. They were staying with Nelson’s boyfriend in San Bernardino. She was now behind in her college courses, and her daughter was out of school for weeks. Her own cat was in foster care.

All the abrupt changes in her world made Nelson feel like she might buckle under the pressure.

“I've got a lot of stressors going on," she said, "but the focus is keeping those who are up there safe.”

She returned to Hauser’s home the following day with Pastor Sal Martinez from Northpark Baptist Church, as well as some cat food. Operation Mountain Strong worked with Mountain Homeless Coalition, a local shelter alliance, to find Hauser a local hotel room and foster homes for the cats.

While Nelson visited with Hauser, they prayed with Martinez in her home.

Hauser then announced that one of her cats had given birth to a litter of kittens.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.