Move to diminish Electoral College faces constitutional roadblocks

In this commentary, Ian J. Drake from Montclair State says a move to change the Electoral College raises serious constitutional questions and would require a constitutional amendment.

In July 2013, Rhode Island became the ninth state to adopt the National Popular Vote (NPV) Interstate Compact. Although the plan retains the Electoral College, it dramatically alters how the College functions.

Currently, all states except Maine and Nebraska award their electoral votes to the candidate who wins the popular within the state. The NPV plan proposes to award states’ electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote.

There have been many proposals to abolish the Electoral College, but the latest, the National Popular Vote (NPV) compact, has received only intermittent coverage in the national media.

Yet, we should all pay heed because the NPV plan is an unconstitutional attempt to do away with the current method of electing presidents.

In a recently published article in Publius: The Journal of Federalism, I argue that the NPV compact is unconstitutional because the Constitution’s Compact Clause requires such interstate agreements to be submitted to Congress for approval.

Thus far, NPV proponents have insisted this compact is of a type that does not need to be submitted to Congress. Additionally and ironically, even if the compact were submitted to Congress, I contend Congress is constitutionally incapable of approving it.

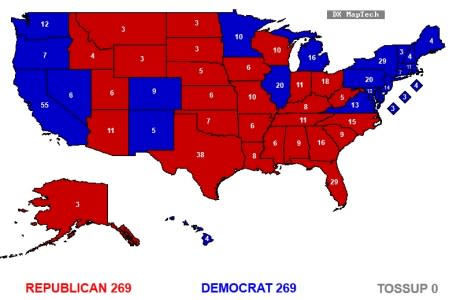

Once the NPV has been enacted in a number of states equal to the 270 electoral votes needed to win the presidency, then the NPV plan will go into effect in each enacting state. Nine states and the District of Columbia have enacted the compact, totaling 136 electoral votes, which total 50.4 of the required 270 electoral votes. With the exception of Idaho, the NPV plan has been introduced with mixed success in the last few years in every state government, often with bipartisan support.

Proponents of the NPV claim it is constitutional and will reflect the democratic preferences of the voters much better than the allegedly antiquated Electoral College. But those claims reveal a misunderstanding of the benefits of the Electoral College system, the purposes of American government, and the role of the Supreme Court.

The origins of the Electoral College

When the Electoral College was proposed the Framers believed that republics were suited to small geographic areas, wherein electors would be prominent citizens with knowledge of candidates and the discernment necessary to make a wise choice for president.

In practice, the Electoral College has been a system of partisan loyalist electors who ratify the popular vote of their respective states.

The winner of the national popular vote usually wins the presidency. Additionally, the Electoral College has manifest benefits: candidates must moderate their views and compete within the two-party system in battleground states. Winners are clear because electoral victories are usually by large margins.

The NPV proposal would present significant new problems: multiple candidates would see incentives to run, with regional candidates being more likely to win and high-density urban population centers being decisive; plurality presidents would be more likely; recounts triggered by a close national vote would be more likely and would be a nightmare on a state-by-state basis; and the states’ role in electing presidents would be eviscerated.

NPV proponents claim no constitutional amendment is needed because the Constitution leaves the appointment of electors to the states.

This is true, but the U.S. Supreme Court will likely object to this plan because it violates the Compact Clause of the Constitution.

The Compact Clause prohibits states from making interstate agreements without Congress’s approval. NPV enthusiasts concede the plan is an interstate compact, but they claim it does not need congressional approval.

The Supreme Court has allowed some interstate agreements without congressional approval, but only those that do not disadvantage states that have not joined the agreement. For example, the Court has allowed agreements resolving state boundaries or multistate tax commissions to exist without congressional approval. However, these are dramatically different from agreeing to intentionally circumvent how the President is elected. Since the NPV compact proposes such a dramatic change to the constitutional system of electing the President, it must be submitted to Congress.

However, Congress is constitutionally incapable of approving the NPV.

The Supreme Court has held that congressional approval of an interstate agreement makes the agreement federal law. The Supremacy Clause prevents Congress from enacting laws contrary to the Constitution.

Congress could not constitutionally create a popular vote system by itself. How could it enact a state-based plan that does the same?

In short, it cannot. Thus, the dilemma facing NPV proponents: the NPV compact must be submitted to Congress but cannot be approved by Congress. Any effort to change the Electoral College system to a national popular vote system will need a constitutional amendment.

Ian J. Drake’s teaching interests include the American judiciary and legal system, the U.S. Supreme Court and constitutional history, and the history and contemporary study of law and society, broadly construed. His research on this topic appeared in Publius: The Journal of Federalism, from Oxford University Press, this month.

Recent Constitution Daily Stories

Reviewing the 14th Amendment debt ceiling argument

Can Tumblr make a difference in the Supreme Court’s campaign financing case?

What if Congress doesn’t increase the debt limit? The risks of default