From movie icons to pioneering political figures: Latinos we lost in 2023

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

An iconic film star. A global diplomat. A World Series champion. A street activist turned crusading journalist. A female political pioneer. They were among the Latinos who left us in 2023. They were artists and activists, dreamers and politicians, renowned personalities and heroic people working away from the spotlight.

As we do every year, NBC Latino takes a look back at the lives and legacies of Hispanics whose contributions enriched the country in different ways.

DR. MAX GOMEZ, 72, TV medical correspondent. Maximo Marcelino Gomez III was born in Havana, graduated from Princeton University and earned a Ph.D. in neuroscience from Wake Forest University School of Medicine. But to millions of viewers in New York City and Philadelphia, he was simply “Dr. Max,” one of television’s most respected and beloved medical journalists. For over 40 years, Gomez helped ordinary people understand medical issues like Covid-19, sickle cell disease and Alzheimer’s disease. He was one of the first TV reporters to spotlight the AIDS crisis, co-wrote several books and discussed adult stem cell research with the Vatican.

Although he received numerous honors, Gomez was especially proud of an award from the New York City Health Department for his reporting on 9/11. “The award from the City is the essence of my core beliefs,” Gomez wrote on his website. “Helping people, keeping them calm and safe during one of the most trying times in New York’s history.”

“Dr. Max was soft-spoken, gentle and kind,” said Cindy Hsu, an anchor and reporter for WCBS-TV. “In the newsroom, people asked him for advice or for recommendations about doctors, and he was always available to help. He never acted like it bothered him.” Hsu credits Gomez with saving her life during a time when she experienced severe depression. “He was never too busy to stop and listen.”

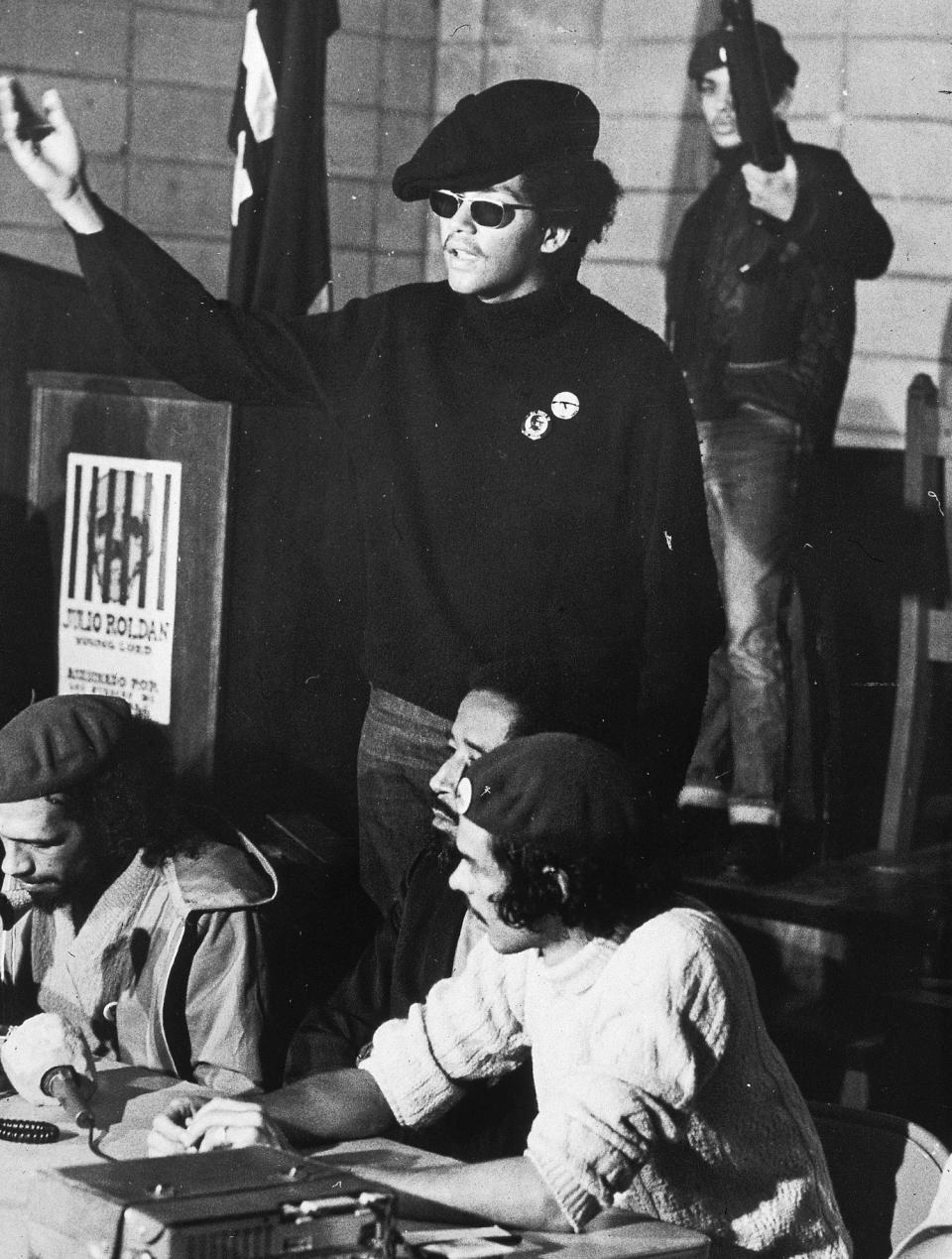

PABLO GUZMÁN, 73, activist and journalist. A graduate of the elite Bronx High School of Science, Guzmán left college in 1969 to co-found the Young Lords, a group dedicated to fighting for the needs of New York City’s Latino residents. Known for their street activism, the Lords became folk heroes to many people of color because they spotlighted poor conditions in marginalized neighborhoods. When the city’s sanitation workers were not picking up trash in Spanish Harlem, the Young Lords piled up the trash and burned it themselves. Such efforts contributed to the rise of the city’s Puerto Ricans as a political force.

“Pablo was a very charismatic figure,” recalled Juan González, a senior fellow at the Great Cities Institute and a former Young Lord. “He was able to charm and disarm the notoriously cynical New York City press whenever he held press conferences.” He called Guzmán “the first great public relations agent of the Latino community” because of his skill at handling the media.

After the Young Lords folded in 1975, Guzmán became a radio host, writer and Emmy award-winning television reporter. He worked for several New York City stations, including nearly 20 years at WCBS, covering 9/11, politics and organized crime. “Pablo was the quintessential New Yorker,” González said, “up from the streets, concerned about the underdog and never flagging in his principles.”

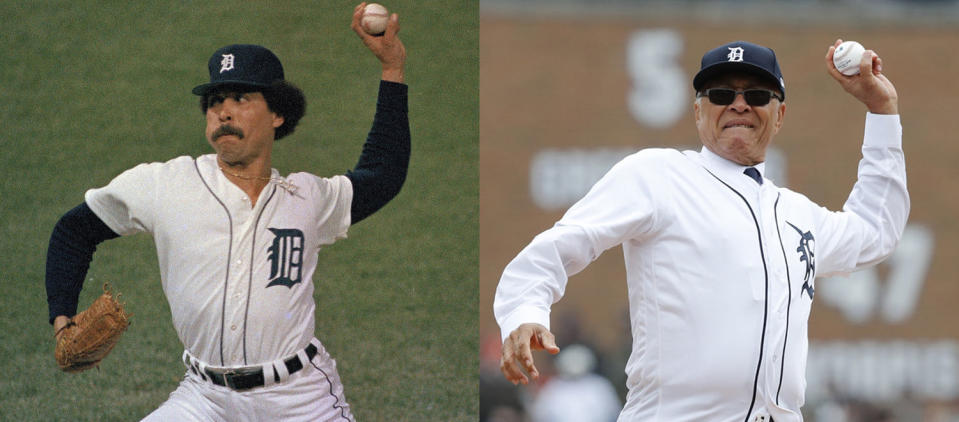

WILLIE HERNÁNDEZ, 69, baseball champion. Growing up in Aguada, Puerto Rico, Hernández loved baseball and joined the Puerto Rican national team as soon as he graduated from high school. He signed with the Philadelphia Phillies before he made his major-league debut with the Chicago Cubs in 1977. But his marquee year would be 1984, when his pitching helped the Detroit Tigers win the World Series. The same season, Hernández was voted the American League’s Most Valuable Player and received the Cy Young Award. He was also on three All-Star teams.

Hernández helped pave the way for other Latino players in major-league baseball, whose overall rosters are about 30% Latino today.

“Willie was a great person, and he helped me a lot during my rookie year,” recalled Bárbaro Garbey, a former teammate on the Tigers. “He was very fun and very competitive. Because all my family was in Cuba, Willie was like the brother I never had in the United States.”

“Hopefully, people will recognize how well Willie represented Latin Americans, Puerto Ricans, his family and his team,” Garbey said.

In a statement, Alan Trammell, another former Tiger, said: “I will never forget our team’s celebration together on the mound after he recorded the final out of the 1984 World Series. He will always be remembered as a World Series champion.”

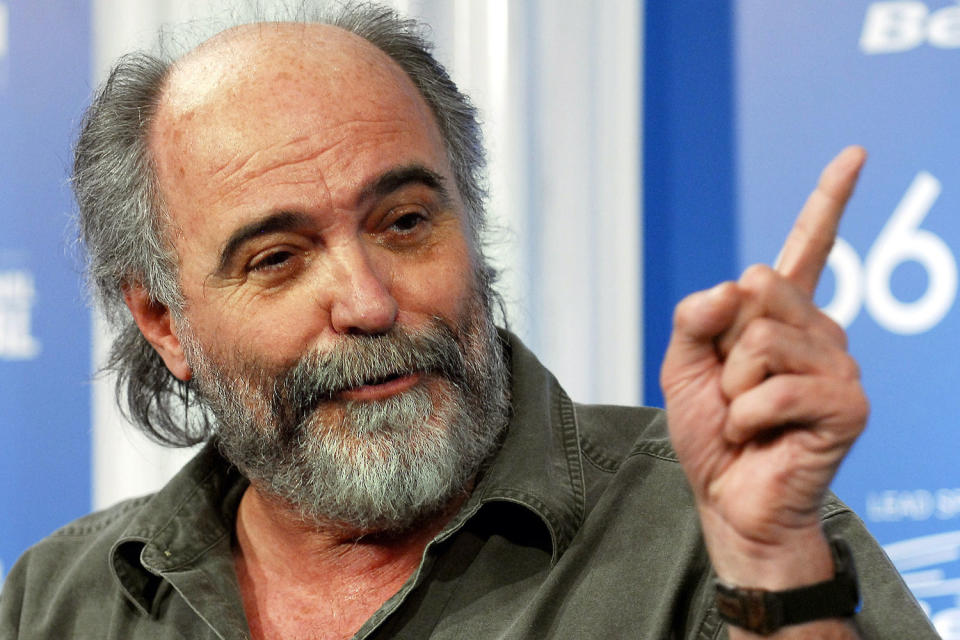

LEON ICHASO, 74, filmmaker. He was working in a Spanish-language ad agency in 1977 when he happened to see an off-Broadway play about a beleaguered superintendent in a New York City building. Two years later, Ichaso had turned the play into his poignant and award-winning first movie, “El Super,” which The Miami Herald termed the “quintessential Cuban exile film.” Ichaso rose to become one of the most prominent Latino directors in the U.S., with films exploring assimilation, identity and exile. He directed "Piñero," a biography of the playwright Miguel Piñero, in 2001, starring Benjamin Bratt, as well as the story of the salsa musical icon Héctor Lavoe in the 2006 film “El cantante” with Marc Anthony and Jennifer Lopez.

Known as “The Poet of Latin New York,” Ichaso depicted Spanish Harlem in “Crossover Dreams” (1985, starring Rubén Blades), Harlem in “Sugar Hill” (1993, with Wesley Snipes) and Washington Heights in “El Super.” For television, Ichaso directed episodes of “Saturday Night Live,” “Miami Vice” and “Chicago Med.” His last film was “Paraiso” (2009), the third in his Cuban exile trilogy, which included “El Super” and “Bitter Sugar” (1996).

“He loved his actors, understood our delicate temperament and nurtured a trust that would embolden you to walk out on a wire with no net,” Bratt told The New York Times. “He was the net, and it was very easy to love him back for this.”

MARIA MARTIN, 72, radio pioneer. From humble beginnings with a small bilingual station in Northern California and a stint at NPR, the indefatigable Martin made her mark by creating “Latino USA,” one of the first Latino-focused nationally syndicated radio shows. She even wrangled President Bill Clinton into attending the show’s 1993 launch party. Her intention for "Latino USA" was “to reflect the diversity of the Latino community in all of its beauty and in all of its pain.”

Throughout her life, Martin elevated Latino and Latin American voices in the media. She trained journalists in the U.S., Guatemala, Nicaragua, Bolivia and Kyrgyzstan. In Guatemala, she founded the nonprofit GraciasVida Center for Media to improve news coverage of Central America. She wrote a memoir, was a Fulbright fellow and was inducted into the National Association of Hispanic Journalists Hall of Fame.

“Maria was a very gentle but passionate person,” said Mandalit del Barco, a culture correspondent for NPR News. “I call her my public radio and journalism ‘madrina’ [godmother].” Del Barco noted that Martin loved radio because it was such a democratic medium; even in places where people did not have computers or could not read, there was often still a radio station.

“She was so dedicated to representing the cultura,” del Barco remembered. “She persevered through a lot of hardships and obstacles. ... She was just unstoppable.”

GLORIA MOLINA, 74, politician. Molina came from a traditional Mexican American household in which the expectation was that she would get married and start a family. She once thought college was for white people. Then she was caught up in the Chicano Movement that swept across Southern California in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Molina became an activist, rising from community organizer to working in Washington, D.C., during the Carter administration.

Molina went on to transform the political landscape of Los Angeles. She was the first Latina elected to the California State Assembly (1982), to the Los Angeles City Council (1987) and to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors (1991). Known for being outspoken and uncompromising, she was never afraid to oppose entrenched power structures. After her death, The New York Times lauded her as “one of the leading Latina politicians in California and the country.”

“Gloria was one of those larger-than-life figures,” said Gustavo Arellano, a columnist with the Los Angeles Times. “She was our tía [aunt]: strongly built, loud voice, very matter of fact and with a great laugh.” In her political career, Molina dealt with racism, sexism and misogyny, Arellano said. “But she stood her ground. She always put her community in front of herself.”

BILL RICHARDSON, 75, ambassador, governor, Cabinet member. On his father’s side, Richardson could trace his roots back to the Mayflower. His mother was from Mexico. And in a storied career spanning 40 years of public service, Richardson never defined himself by his ethnicity. Instead, he amassed an amazing résumé: 14 years in Congress, two terms as governor of New Mexico and Cabinet positions as U.N. ambassador and energy secretary in the Clinton administration. In 2008, he was the first Latino to run for the Democratic nomination for president.

After his political career, Richardson achieved prominence as a diplomat and special envoy on the global stage. His humanitarian missions rescued detained Americans from countries like Iraq, Afghanistan and North Korea. Last year, he helped secure the release of WNBA star Brittney Griner from Russia.

“What always struck me about Richardson is how straightforward and unassuming he was,” said Arturo Vargas, the CEO of the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials, or NALEO. “He did not put on airs. He was interested in policy and trying to do the right thing for his constituents and for the country.” To Vargas, Richardson “showed the deep level of talent within the Latino community.”

Upon his passing, President Joe Biden remembered Richardson as “a patriot and true original.”

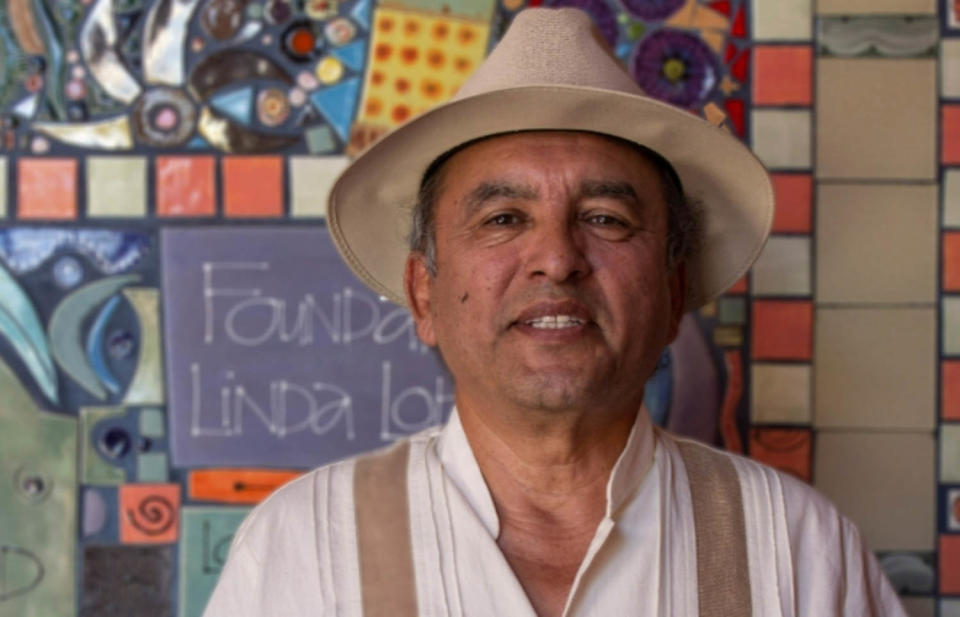

ROBERTO RODRIGUEZ, 69, author and activist. Rodriguez was in East Los Angeles in 1979 on the day his life changed. Witnessing an episode of law enforcement brutality, he began taking photos, only to have sheriff’s deputies turn on him, severely beating and arresting him. After three days in the hospital, Rodriguez spent seven years pursuing a civil case, an experience he wrote about in his book “Justice: A Question of Race.” Rodriguez was cleared of all charges and awarded over $200,000 by a jury in 1986. He later co-founded a national database of Latinos killed by law enforcement.

Despite living with post-traumatic stress disorder, Rodriguez co-wrote a syndicated column with his wife, taught at the University of Arizona and contributed to numerous publications. He was particularly interested in maíz (corn) and how it was foundational to Mexican and Indigenous cultures. For this, he was known by many colleagues and students as “Dr. Cintli” (“cintli” was the Aztec word for corn).

“Roberto was an inheritor of hundreds of years of Indigenous struggle for human rights,” said his former wife, Patrisia Gonzales. “All of his messages were about our shared humanity, what happens with dehumanization — and how it can shape our journey to be really good human beings.”

“He certainly had anger towards injustice,” Gonzales added. “But he was a positive person, with a unique spirit. He truly was a bright star.”

JESSE TREVIÑO, 76, artist. Raised in San Antonio, Treviño was a young man studying art in New York City when he was drafted into the Vietnam War. There he stepped on a land mine and nearly lost his life, an incident that earned him a Purple Heart — and resulted in the amputation of his dominant right arm. As a helicopter airlifted him out of the Mekong Delta, Treviño vowed that, if he survived, he would put the people of his beloved city on canvas.

Back in Texas, Treviño trained his left arm to paint, thereby regaining his full artistic talent. With his murals, sculptures and paintings, he established himself as one of San Antonio’s most accomplished and prolific artists. He won national attention for depicting the everyday lives of Mexican Americans on the city’s west side, changing how Americans saw Texas art and how they viewed Texas. His works are displayed in the Smithsonian Institution and three presidential libraries.

“San Antonio meant the world to Jesse. He considered the city his muse, his inspiration and his canvas,” said Anthony Head, the author of “Spirit: The Life and Art of Jesse Treviño.”

“He believed that his neighborhood, the trucks, the lady selling raspadas [snow cones] on the corner, were all beautiful and deserved to be seen by the world,” Head said. “The west side of San Antonio was truly his heart and soul.”

RAQUEL WELCH, 82, actor. The star of “One Million Years B.C.” and “The Three Musketeers” was born Jo-Raquel Tejada, as her father was of Bolivian heritage. Resisting studio demands that she change her name to Debbie, she achieved international fame at a time when “Hispanic” and “Latino” were unknown constructs. “Her heritage was always there, always visible, and it was not a secret,” said theater scholar Brian Herrera of Princeton University. “Welch was in a complicated space about it, and she arrived in a transitional period of how Latinos are understood in the U.S.”

Despite her bombshell image, Welch played roles as varied as a transgender woman (“Myra Breckinridge”), a victim of ALS (“Right to Die”) and a TV journalist (Broadway’s “Woman of the Year”). Off-screen, she set a precedent for workers’ rights when she sued MGM for replacing her in a film with a younger actor. She won a $10 million verdict in 1986 in a legal victory against sexism and ageism.

By the early 2000s, Welch reclaimed her heritage, telling the National Press Club: “Latinos are here to stay. As citizen Raquel, I’m proud to be Latina.” That sparked a career renaissance, with roles in Latino-themed projects like “American Family” and “How to Be a Latin Lover.”

“She went through a lot of stages in her career,” author Luis I. Reyes said. “She really represented the Latino fusion of contributions to American culture and the complexity of the Latino experience.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com