MS Coast loses legal legend, gifted storyteller who kept secret his habit of giving

Albert Necaise was one of the last of the legendary Coast attorneys who operated without a smart phone or computer, capturing the attention of jurors and winning verdicts through hard work, a reverence for the law and a gift for storytelling.

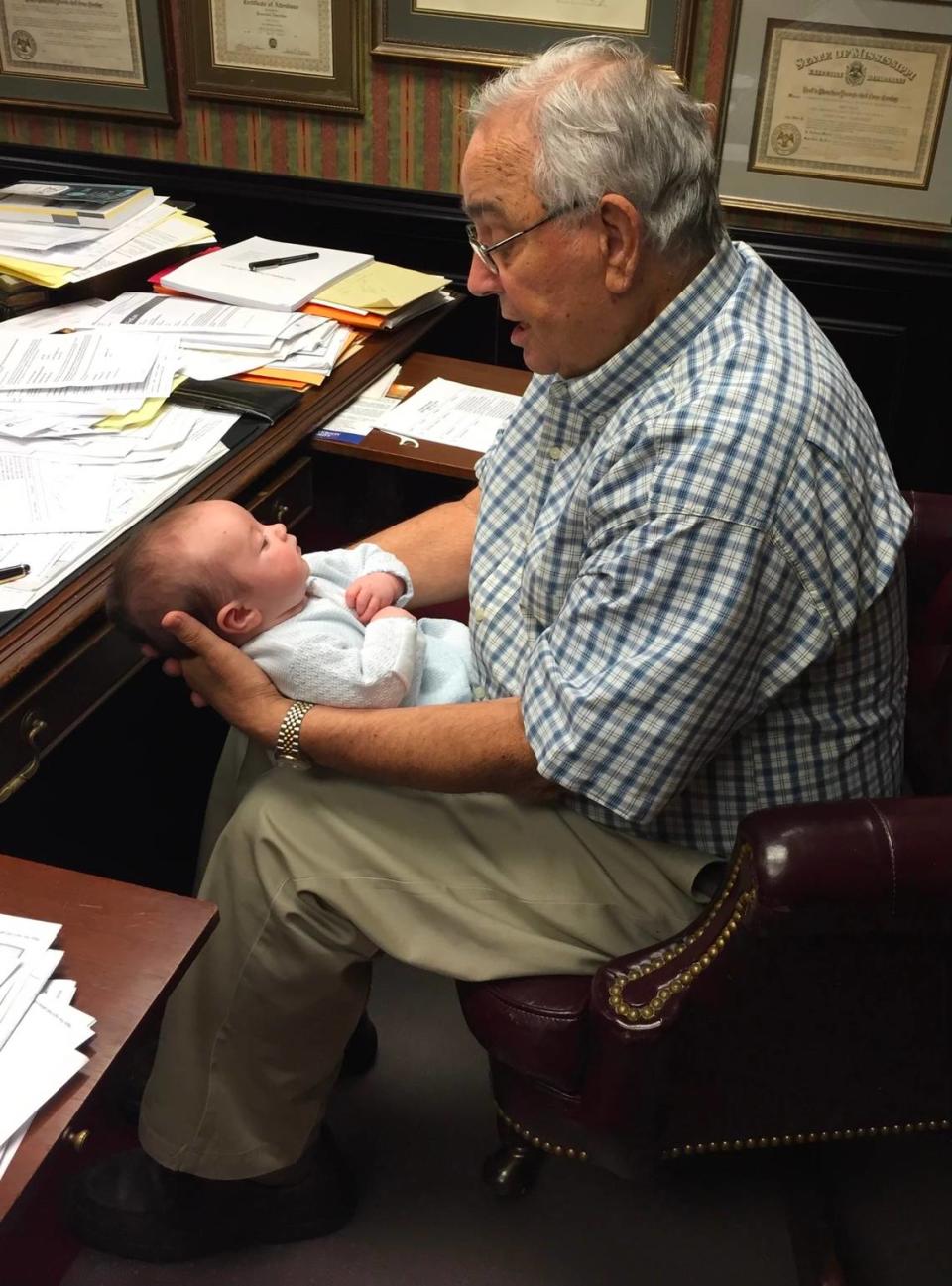

Necaise passed away Sunday, Nov. 19, at his home in Orange Grove with his wife of 65 years, Lois Ann Necaise, by his side. The 87-year-old had experienced numerous health setbacks over the previous two years. He was done with hospitals. He just wanted to be home.

“He was just one of those people,” said Lauren Esposito, his paralegal for 30 years. “He was larger than life. He just had a presence.”

“I don’t know of another Albert Necaise, I’ll say that.”

His Catholic faith, family and the law were the cornerstones of Necaise’s life. Michael Necaise, the second of three children, said his father spoiled them because he spent so much time working. As a youngster, while his friends cut school to fish, Albert Necaise headed to the courthouse so he could sit in on trials.

“He just loved, loved the law,” Michael Necaise said. “He had planned his entire life to be an attorney. That’s what he wanted.”

Spirit of giving

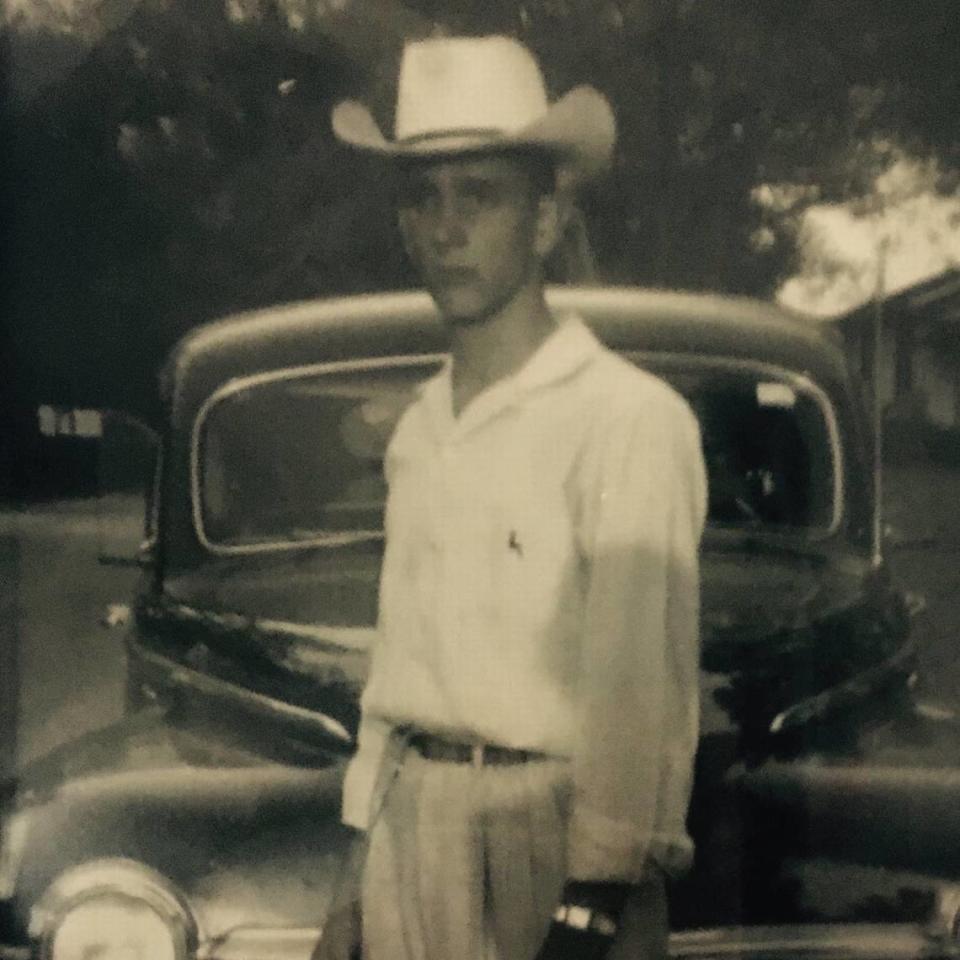

Albert Necaise was born and raised in Gulfport, the only child of Herbert and Mamie Necaise. His father was a sheet metal worker and roofer, while his mother ran a hotel in New Orleans.

Necaise worked from the time he was a small child, hauling butter in a wagon pulled by his goat Billy from a local dairy to neighborhood markets, where he sold the wares for a small markup. He eventually saved enough money to buy himself a used bicycle.

He received a Catholic education before attending community college and then the University of Southern Mississippi, where he was introduced to his future wife, Lois Ann Walker. She remembered him from the first time they met, when she went as a teenager to buy medicine at the Gulfport drugstore where he was working.

They started dating and married within a year. They became the parents of three children in quick succession: Ann, followed by Michael and then, exactly one year later, Brian. Michael Necaise is still not sure how his father managed to graduate from law school at what is now Mississippi College School of Law.

Albert Necaise opened a small law office in Gulfport before going to work in the District Attorney’s Office for Boyce Holleman, a mentor who also relied on a quick wit and gift for storytelling to capture a jury’s attention.

When Holleman left the job in 1971, he tried to convince Necaise to work in his law office, but Necaise wanted to be district attorney. He was elected to the job and served for 12 years.

When he returned to private practice, he wound up representing some of the criminals he had convicted as district attorney. They knew he was a good lawyer, Michael Necaise said. “They all said the same thing about dad: He was hard but he was fair,” his son recalled.

Like Holleman, Necaise knew how to charm a jury. It started with jury selection, said Gulfport attorney Steve Simpson, who recalled the way Necaise connected with jurors. Necaise might launch into a story about a mutual acquaintance, for example.

“He was just a great storyteller, great storyteller, which in trial practice is the key to your success,” said Simpson, who worked as a diversion officer in the District Attorney’s Office under Necaise. Necaise noticed how Simpson seemed to love the law and talked the young man into going to law school.

Robin Midcalf, now a County Court judge in Harrison County, also worked for Necaise while he was DA and before she became a lawyer. He was always checking in to make sure she kept up her grades because he knew she wanted to go to law school.

“We’ve lost one of our legends of the legal community,” Midcalf said. “I will put him up there with the likes of Boyce Holleman.”

She remembered Necaise’s generosity, something he never advertised because, in his mind, that defeated the purpose of giving.

“The man was very generous,” she said. “He helped a lot of people.”

“He’d hear a sob story and open his wallet. I’ve seen that. I don’t know how many times I saw it. It’s not something that you would expect. He certainly did not want any accolades for it.”

Necaise served for decades as attorney for the Harrison County School District. He handled all the district’s legal business, former Superintendent Henry Arledge said, telling his clients what they needed to hear, even when it wasn’t what they wanted to hear.

Each Christmas, Necaise picked a family in need and donated everything from the turkey and fixings to presents for the children, with gifts the children could give their parents included, too.

Hopping from one courtroom to the next

Necaise worked long hours. Former paralegal Lauren Esposito recalls that he would run from one courtroom to another, often returning at nightfall to an office full of clients

“People would just wait to see him,” she said. “They loved visiting with him.”

He was always late to court. Always. He knew his cases well, though, and when he’d get a call from the courtroom, where an irate judge was waiting on him, he’d rush out the door. An attorney hates to walk into court without his paperwork, so he would say, “Just give me an empty folder,” Esposito recalled.

One time, a judge who had once worked as one of Necaise’s assistant district attorneys, was tired of the lawyer being late to court. He decided to fine Necaise $100, Michael Necaise recalls. The judge agreed Necaise could donate the fine to a charity called Hope Haven. Necaise then talked the judge, James Thomas, into donating the same amount to the charity.

During a break, Thomas asked Necaise, “How come you’re late for court and it cost me $100?”

Esposito said that Necaise carried a flip phone because he needed it only for calls and never used a computer. He studied his case files and shot from the hip in court. “I don’t remember him ever sitting down and preparing a closing argument,” she said. “He could pull some rabbits out of a hat.”

Necaise believed in second chances

On his 50th anniversary as a lawyer, Necaise was honored with a reception at the Great Southern Club. Federal and state court judges, a Mississippi Supreme Court judge and many lawyers showed up.

The occasion was supposed to be a surprise, but Michael Necaise isn’t sure his family and friends pulled it off. Albert Necaise seemed to know everything before it happened in the legal community.

“Dad’s grapevine was fiber optic,” he said.

Albert Necaise worked until he couldn’t, Esposito said. A couple of years ago, he just grew too weak to make it to court.

He is now at peace, his family said. His granddaugher Lauren Williams held his hand the day before he died. As she got ready to leave, she told him that she would see him the next morning, although she was doubtful. He gave her his trademark half-crooked smile and winked.

Both Williams and Michael Necaise said one of the biggest lessons they learned from Albert Necaise was to give people second chances. In fact, he was known to dispense even third and fourth chances.

“Everybody,” his granddaughter said, “deserves to have another chance.”