After much fretting over 'CRT' law, one mostly Black Oklahoma school district sees little impact on teaching of racism

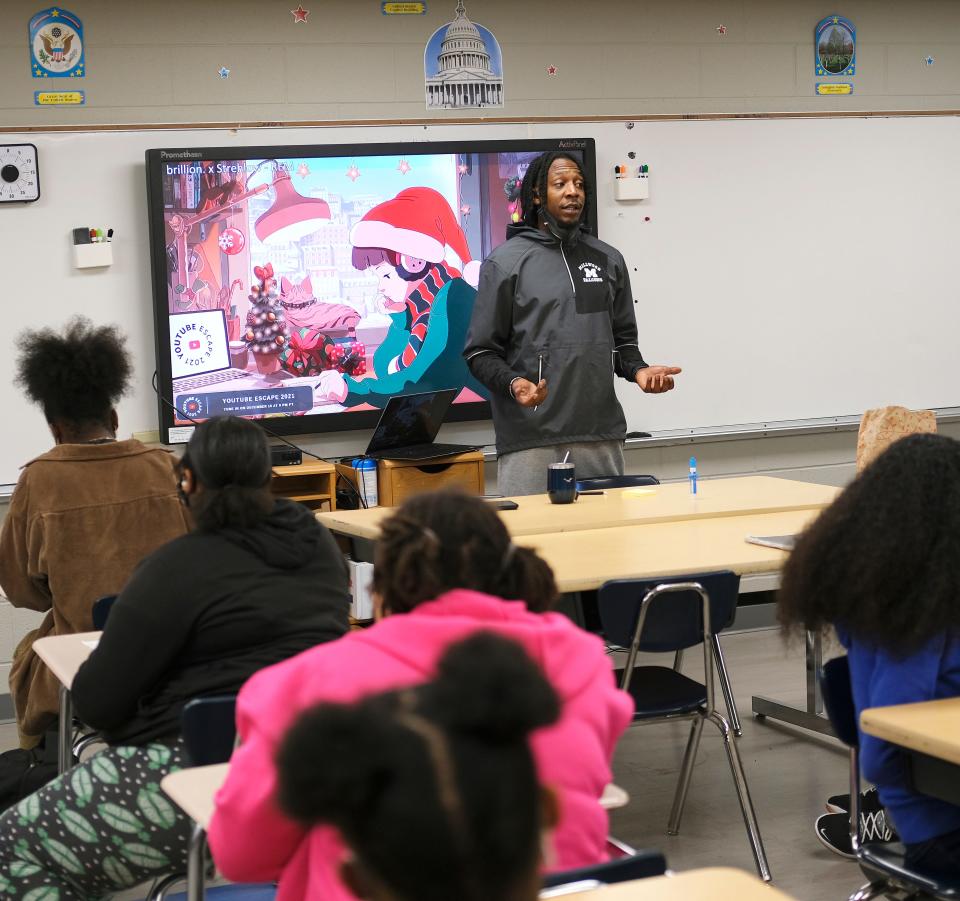

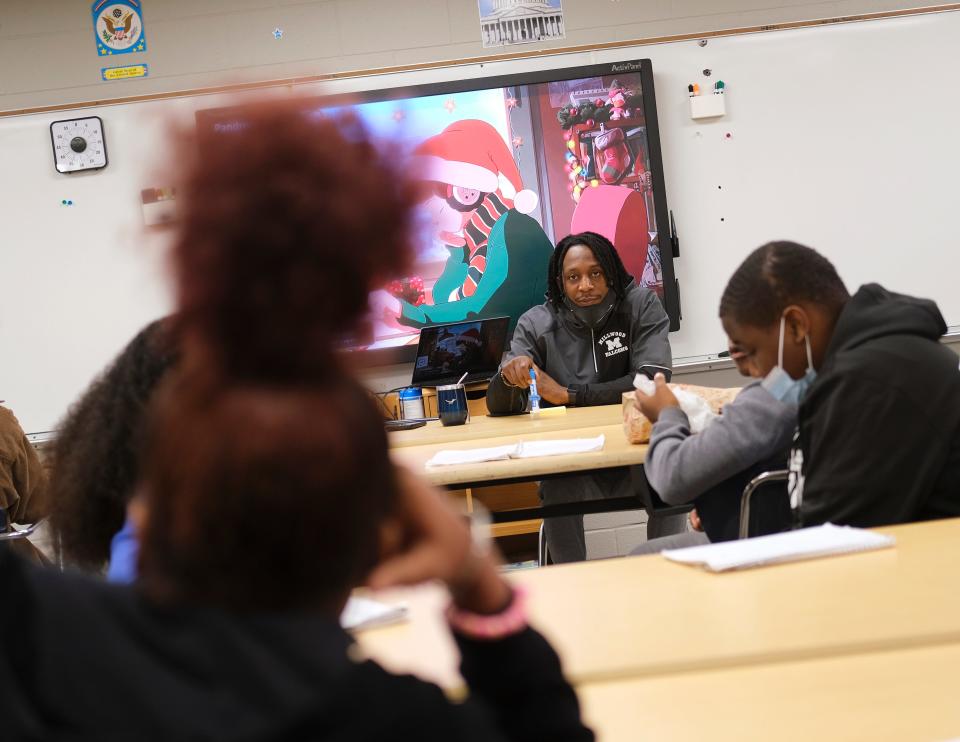

After the destruction of Greenwood flashed on a screen, middle school teacher Chevis Smith had some questions for his students.

Why did people use violence in 1921? Why was it an option to use violence? How can we recover?

The Millwood Arts Academy history teacher peppered his class with one follow-up after another. His sixth- and eighth-grade students had just watched a scene depicting the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, which leveled an affluent Black neighborhood of homes and businesses.

Drafting Oklahoma HB 1775: Penalties, a resignation, rush to finish

Smith said he doesn’t teach this chapter of history to convince students that “you came from nothing or that one race is greater than another.”

“It’s knowing what your ancestors have been through to know where you’re going,” he told the class.

More: As critical race theory stirs national debate, Oklahoma bill seeks to alter teaching of slavery

Smith’s questions to his class were asked with a new Oklahoma law in the back of his mind.

House Bill 1775 forbids K-12 schools from teaching that one race is superior to another. It also blocks schools from teaching that a person is inherently racist or oppressive or that students should feel guilt or anguish for past actions by others of their race or sex.

The highly controversial law evoked fears when the Legislature passed it earlier this year from some who worried it would have a chilling effect on classroom discussions.

Smith said he was concerned, too, but his worries disappeared when he learned the bill didn’t change any of the Oklahoma Academic Standards, which dictate the subjects public schools must teach.

“I don’t teach one race to be greater than another race or that you’re disadvantaged because you are this race,” Smith said. “I never taught that. I would never even want my kids to know things like that. So, it just simplified everything for me.”

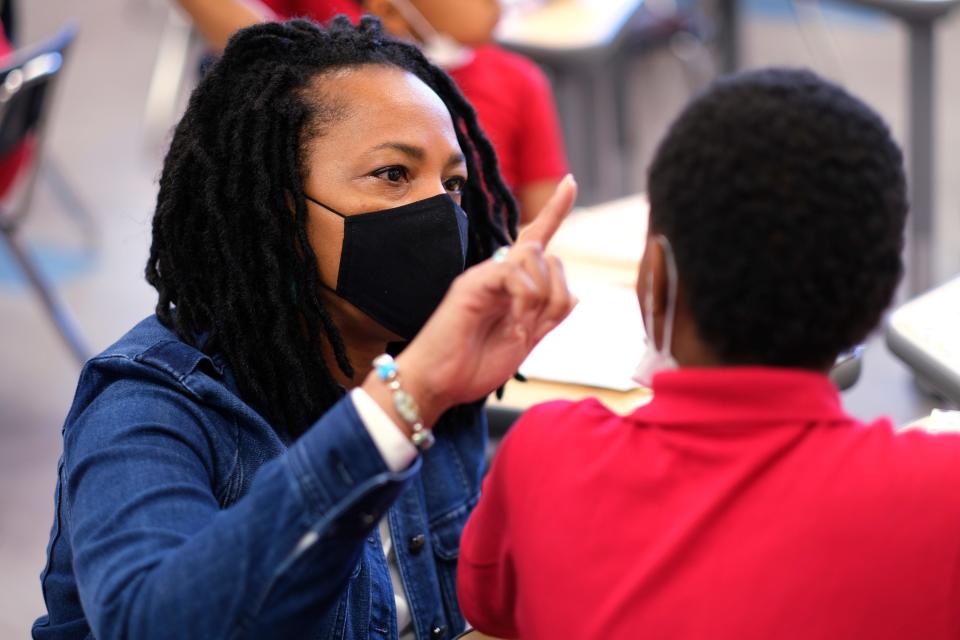

A predominantly Black school district in northeast Oklahoma City, Millwood Public Schools has about 875 students. The district doesn’t shy away from discussions of race and inequality, said Cecilia Robinson-Woods, district superintendent.

She said the district’s parents and school board expect teachers to broach these subjects. So, Millwood trained its teachers to carry out culturally responsive instruction while abiding by HB 1775.

More: Salvation Army leader reassures donors amid critical race theory controversy

“We know, we live it and we experience it, and schools are a reflection of society,” Robinson-Woods said. “So, there really is no credible way or no authentic way for us to reach our children without acknowledging some of these tough conversations.”

Support in city for race education

In a state where criticism over critical race theory has fueled school board debates and legislation aimed at controlling classroom lessons, Oklahoma’s largest city mostly supports the teaching of America’s troubled past.

Seventy percent of Oklahoma City residents said they support public schools teaching the history of racism in this country and how that history has shaped the country, according to a recent survey by Suffolk University and the USA TODAY network.

That the more left-leaning Oklahoma City would be in favor of this approach to the teaching of history reinforces the urban-rural partisan divide that can be found across the country on most political subjects, including race.

When Oklahoma’s Republican-majority Legislature approved HB 1775 this year, it did not include the phrase “critical race theory,” even though it was very much top of mind for lawmakers when they crafted the legislation.

More: Edmond school superintendent responds to 'negative and sometimes false' comments from parents

Some districts have tiptoed around their history curriculum, navigating complaints from both sides of the debate.

But in Millwood, teachers say there has been no impact.

“It didn’t really impact us because when I did more research on the law, the critical race theory, that is a college — not even college, a master’s course that you do in your graduate program,” said Anthony Crawford, an English teacher at Millwood High School, referring to the academic concept of critical race theory, which includes a belief that racism goes beyond personal beliefs and is systemic.

Crawford said he was worried when the law was first passed, but his concerns have subsided.

“I was worried and nervous for no reason. It didn’t really affect things in my classroom because we’re still teaching what we can,” Crawford said.

Lawsuit over bill

Despite the law’s lack of influence on his lesson plans, Crawford is part of a group of plaintiffs suing to overturn HB 1775.

The lawsuit, led by the ACLU of Oklahoma, is pending in Oklahoma City federal court against Gov. Kevin Stitt, Attorney General John O’Connor, state schools Superintendent Joy Hofmeister, the Oklahoma State Board of Education, the Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, and Edmond Public Schools’ superintendent and school board.

It contends the bill dissuades schools from allowing conversations on sensitive subjects for fear of breaking the law.

More: Lawsuit challenges state law banning certain race topics from classrooms

An Edmond high school teacher claimed in the lawsuit that his district told him to avoid books by non-white and female authors in his English class. The books included "To Kill a Mockingbird" and "A Raisin in the Sun." The Edmond district denies excluding these books, and a review of Edmond’s high school reading lists show several titles by women and non-white authors.

HB 1775 doesn’t change academic standards, which require schools to teach about America’s history of racial tensions, said one of the authors of the bill, David Bullard, R-Durant.

“We did that so that argument cannot be made that we’re preventing the history from being taught,” said Bullard, who is a former high school history and government teacher. “I think if people will read the bill, they will understand how flawed the argument is that the ACLU is putting out because all you have to do is go read the bill and you’ll understand that that’s not the case.”

Many questioned whether the topics addressed in HB 1775 needed to be legislated in the first place.

While the bill progressed in the Legislature, Oklahoma City Public Schools Superintendent Sean McDaniel called it a "solution looking for a problem which does not exist."

Robinson-Woods said HB 1775 hasn’t changed what is taught at Millwood, and rather than addressing a concrete issue, it seems to play into misguided fears.

“I think the law was somewhat created to give people, who were looking for a fight, a weapon to go to school districts and say, ‘You’re doing this,’ but nobody can really tell you what the ‘this’ is,” Robinson-Woods said. “I really do think they just needed something to hold, and they found something to hold.”

The new law set up a process for complaints to be filed if a person believes educators are violating the new rules. But, Robinson-Woods said the district hasn't received any such complaints.

Only two complaints have been made directly to the state Education Department. One complaint was that the Tulsa Public Schools board had not voted on an HB 1775 policy, which a board isn’t required to do. The other complaint dealt with a geography quiz having non-geography questions that the state Education Department reviewed and determined was not in violation of the new law.

While support is high in Oklahoma City, statewide there is strong opposition to critical race theory and its concepts. A majority of Oklahomans, especially among Republicans, oppose critical race theory in schools, according to a CHS & Associates poll from August.

That opposition has put some school systems on the defensive, trying to explain to parents and community members that critical race theory, or any curriculum banned by the new law, isn’t a part of their school.

Oklahoma’s largest teachers union said allegations of HB 1775 violations haven't cropped up among its membership. The union said none of its members have asked for help or representation over an HB 1775 complaint.

“The effect of HB 1775 on teaching or classroom discussions is not the issue we are hearing about,” Katherine Bishop, president of the Oklahoma Education Association, said in a statement to The Oklahoman. “The feedback from our members is that they are concerned about the need for more time to teach and prepare for class. A larger-than-normal workload because of a lack of substitutes and additional responsibilities coming out of the pandemic are also overwhelming issues this year.”

The Oklahoma City chapter of American Federation of Teachers, which represents educators in Oklahoma City Public Schools, said it hasn't had to assist any teachers who were the subject of an HB 1775 complaint, either.

'Unpack standards'

In Millwood, where more than 90% of the student body is Black, Robinson-Woods said there is a particular effort made to ensure the experiences of minority students are reflected in lesson plans, even if it means highlighting the nation’s complicated racist past and how it continues to impact society today.

The district incorporates both the history and contributions of people of color into its curriculum.

“We have to be intentional about doing this because if we don’t infuse the works of Cesar Chavez, you won’t know his contributions to immigration. If we don’t tell you about Shirley Chisholm, then you’ll think that Kamala Harris is the first African-American associated with presidency,” Robinson-Woods said. “That is important that every school district has to unpack standards and align them to the communities they service. You have to or you’re not doing your job.”

It’s critical for students to learn the history of their ancestors, Smith said, but for Black students learning about the Tulsa Race Massacre, the past doesn’t have to represent the present.

Instead, Smith said history should inform the future and whom these students choose to become.

“I’m just teaching you history that happened before you,” Smith said. “Since you have the information, what decision are you going to make next?”

Reporter Nuria Martinez-Keel covers K-12 and higher education throughout the state of Oklahoma. Ben Felder covers state government. Have a story idea for Nuria or Ben? They can be reached at nmartinez-keel@oklahoman.com and bfelder@oklahoman.com. Support Nuria and Ben’s work and that of other Oklahoman journalists by purchasing a digital subscription today at subscribe.oklahoman.com.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: School in OKC sees little change from 'CRT' law on racial topics