How much can Ketanji Brown Jackson accomplish in the minority?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson is already making her mark on the Supreme Court. Since taking her place on the bench earlier this month, she's certainly talking a lot more than her colleagues — The Washington Post reports that by the end of her first eight hearings on the court, she had already spoken more than 11,000 words during oral arguments. "That's about double the nearly 5,500 words spoken by runner-up Justice Sonia Sotomayor."

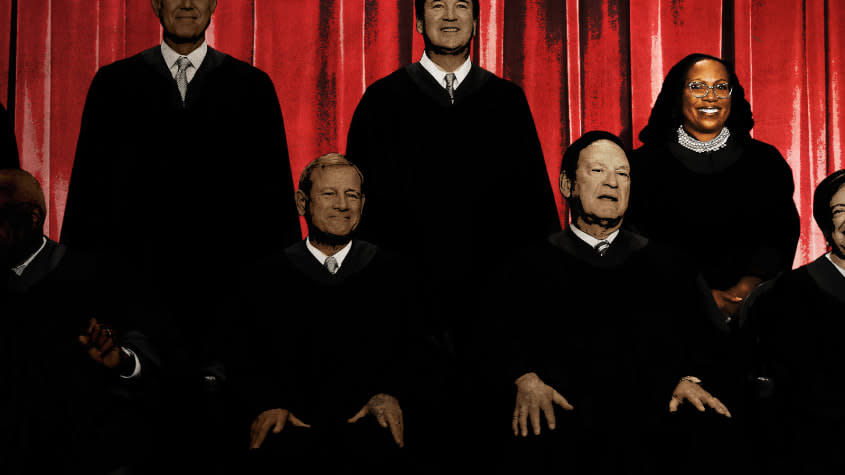

Brown's presence hasn't just been felt in the sheer volume of words she's spoken, but how she's engaged in arguments over cases before the court. "I think it's really clear she's just going to be a force to be reckoned with," the University of Michigan's Leah Litman tells The Guardian. "Both in questioning positions that she's skeptical of, but also in providing support for lawyers when they're being subject to hostile questioning." But if Jackson is vocal and sharp, she's still part of a three-justice liberal minority on a court dominated by six conservative justices. What do her first weeks on the Supreme Court tell us about what kind of justice she will be? Here's everything you need to know:

She'll battle conservatives on their own terms

"Originalism" is a term usually associated with the court's conservatives, but Jackson quickly showed she is willing to make originalist arguments for progressive ends. In an Alabama voting rights case, for example, she pushed back against the notion that the Constitution is always supposed to be blind to racial considerations. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, she argued, were "race-conscious" additions to the Constitution, designed "to ensure that people who had been discriminated against, the Freedman, during the Reconstruction period, were actually brought equal to everyone else in society."

Jackson's position, USA Today noted, is that originalism — which emphasizes taking the Founders' original intent and understanding of the Constitution — "shouldn't always lead to an outcome that favors the conservative position." That doesn't mean conservatives will be swayed in the case, which challenges Alabama's decision to create just one Black-majority congressional district in the most recent round of redistricting. "There's little doubt that the conservative justices will still outvote her here," Mark Joseph Stern writes for Slate, but "at least Jackson won't let them do it without a fight."

Her legal background will quickly come into play

Before she ascended to the federal bench, Jackson's early career included time as a federal public defender — a rarity on both the Supreme Court and the federal judiciary more broadly. "The pipeline from being a corporate attorney or prosecutor to judge is robust. By contrast, the public-defender-to-judge pipeline barely exists," Vox noted in May. One recent study suggests fewer than 10 percent of federal judges have served as public defenders.

That background may already be affecting the court's docket. "Jackson is expected to side with criminal defendants in cases involving sentencing and search and seizure more often than her predecessor, Stephen Breyer," Jordan S. Rubin reports for Bloomberg Law. (Indeed, she already cast a dissenting vote in a death penalty case involving racist jurors at the original trial.) Rubin points out that the court may take up the case of Dayonta McClinton, who was convicted of robbing a pharmacy but found not guilty of murdering one of her fellow robbers. The judge in that case still sentenced McClinton to 19 years in prison, though a robbery conviction usually results in a punishment of five years. Before Jackson joined the Supreme Court, it seemed unlikely to examine the matter. One lawyer told Rubin that "the odds are reasonably good that Jackson is more skeptical" of the harsher punishment than Breyer would've been.

But she's still in the court's minority

Even if Jackson changes the court's dynamics, though, she's inescapably — for now — part of a three-justice liberal minority that is unlikely to get its way on the big issues. As Slate's Stern noted, the Supreme Court is likely to rule in Alabama's favor in the Voting Rights Act case, and Jackson already signed onto the dissent in the death penalty case. Barring some big shifts in the court's composition, Jackson's immediate future looks like it will involve a lot more dissents.

Jackson, along with Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor, won't get to "write the opinions that win the day in the most important rulings of the term," writes Boston Globe columnist Kimberly Atkins Stohr. Those cases include rulings on affirmative action, how states run elections, and LGBT rights. "Far more often than not, they will be dissenters." Which means that even though Ketanji Brown Jackson has already made a big impression in her first weeks on the court, she's still limited by simple math: Six beats three, every time.

You may also like

Are electric vehicles really better?

Special Counsel John Durham's final case goes to the jury after a series of prosecutorial setbacks