A mud lake on Mars might be hiding signs of life in chaotic terrain

Planetary scientists want to search for biosignatures in what they believe was once a Martian mud lake.

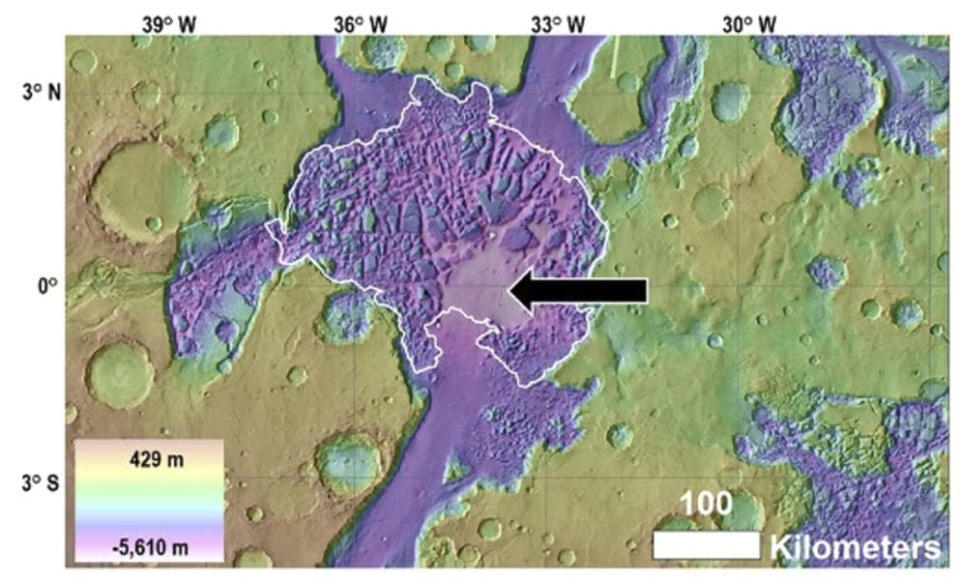

After scientists carefully studied what they believe are desiccated remnants of an equatorial mud lake on Mars, their study of Hydraotes Chaos suggests a buried trove of water surged onto the surface. If researchers are right, then this flat could become prime ground for future missions seeking traces of life on Mars.

"While Martian lakes and mud volcanoes have been subjects of prior studies, our work represents the first comprehensive analysis specifically focused on a putative mud lake," Alexis Rodriguez, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona, told Space.com.

More generally, scientists suggest surface water on Mars froze over about 3.7 billion years ago as the atmosphere thinned and the surface cooled. But underground, groundwater might still have remained liquid in vast chambers. Moreover, life forms might have abided in those catacombs — leaving behind traces of their existence.

Related: Water on Mars carved deep gullies and left a 'great puzzle' for Red Planet history

Only around 3.4 billion years ago did that system of aquifers break down in Hydraotes Chaos, triggering floods of epic proportions that dumped mountains' worth of sediment onto the surface, the study suggests. Future close-up missions could someday examine that sediment for biosignatures.

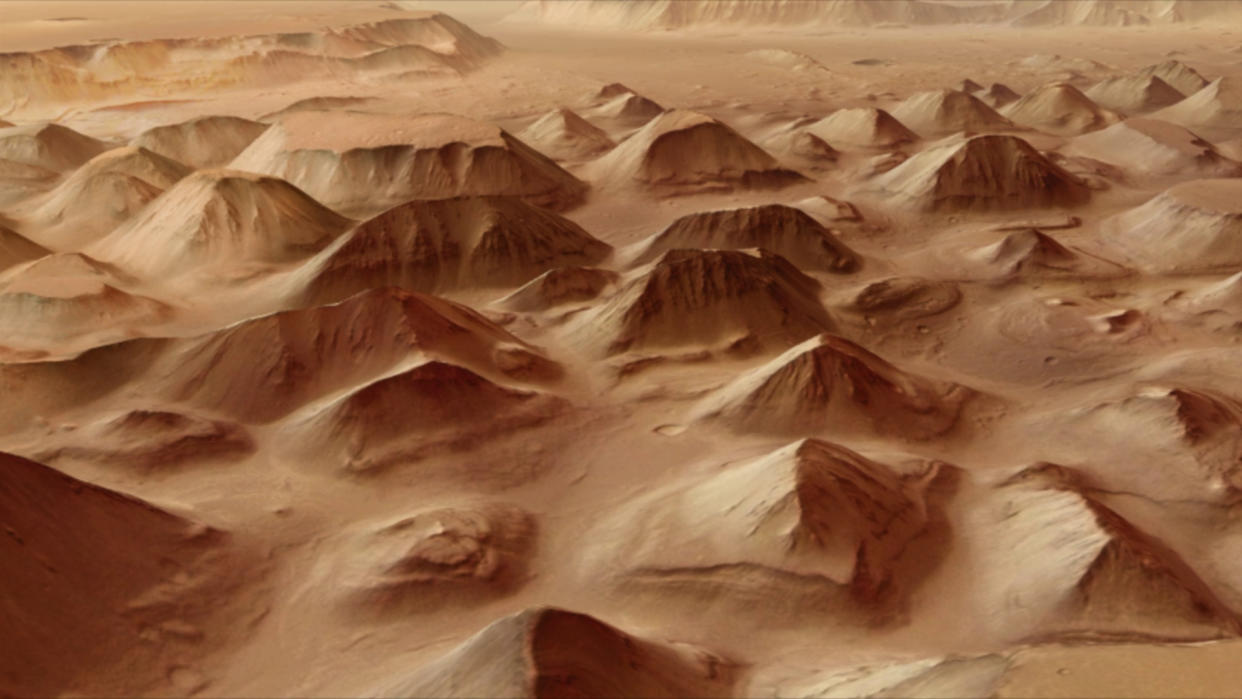

Hydraotes Chaos is an example of geography called chaos terrain: a jumble of jutting mountains, broken craters, and jagged vales. Rodriguez and colleagues pored over images of Hydraotes Chaos taken by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter in search of more clues.

In the midst of the chaos terrain's maelstrom lies a calm circle of relatively flat ground. This plain is pockmarked with cones and domes, with hints of mud bubbling from below — suggesting that sediment did not arrive via a rushing flash flood, but instead rose from underneath.

Related: Scientists discover signs of 'modern' glacier on Mars that hints at buried water ice

Based on simulations, the authors suggest Hydraotes Chaos overlaid a reservoir of buried biosignature-rich water—potentially in the form of thick ice sheets.

Ultimately — potentially from the Red Planet's internal heat melting the ice — that water bubbled up to the surface and created a muddy lake. As the water dissipated, it would have left behind all those tantalizing biosignatures.

Curiously, that water might have remained underground even after those megafloods. In fact, the authors' results suggest the sediment on the surface of this mud lake dates from only around 1.1 billion years ago: long after most of Mars's groundwater ought to have flooded out, and certainly long after Mars was habitable.

Related stories:

— Landslides on Mars suggest water once surrounded Olympus Mons, tallest volcano in the solar system

— Mars' water may have come from ancient asteroid impacts

— Water on Mars may have flowed for a billion years longer than thought

With that timeline in mind, Rodriguez and colleagues plan to analyze what lies under the surface of the lake. That, Rodriguez tells Space.com, would allow scientists to establish when in Martian history the planet might have hosted life.

Scientists might even be able to take future research right into the ancient mud. NASA’s Ames Research Center is working on an instrument called Extractor for

Chemical Analysis of Lipid Biomarkers in Regolith (EXCALIBR) that would test extraterrestrial rocks for biomarkers: in particular, lipids. A future NASA mission might take EXCALIBR with it to the moon or Mars. "Hydraotes Chaos is under consideration as a candidate landing site for [EXCALIBR]," Rodriguez told Space.com.

This research is described in a paper published Wednesday (Oct. 18) in the journal Nature Scientific Reports.