'So muddy it looks like pudding.' Sweet Home grapples with drinking water amid drawdown

Story updated at 3:46 p.m. on Sunday, Nov. 16

It’s a point of pride in Sweet Home that the city has Oregon’s most delicious drinking water. They’ve even got the award to prove it.

The town of 10,000, nestled in the Cascade Foothills, is surrounded by deep forest and clear streams that roll into the town’s drinking water source at Foster Lake.

Last April, the city’s water won a blind taste test and was awarded “best tasting overall water” by the Oregon Association of Water Utilities. It was even sent to Washington, D.C., to represent the state.

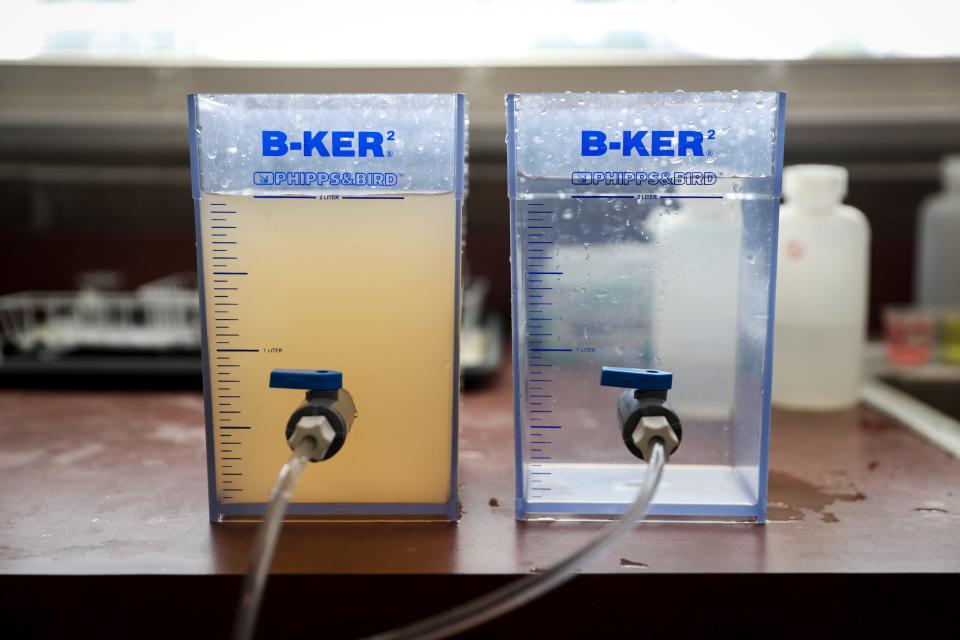

“Normally, our water is just about pristine,” Sweet Home public works director Greg Springman said.

That’s made the past month feel all the more disorienting, as the city’s streams and reservoirs turned the color of chocolate milk. Not just after one major rainstorm, but for weeks at a time.

“Sometimes it gets so muddy it looks like pudding,” Sweet Home mayor Susan Coleman said.

The city’s public works crew has worked 24-hour days to filter and treat the water to keep it safe for drinking, taxing their facilities to the limit. They worry they will eventually need $5 million to replace water filters. And even after all that work, some residents said the odd color and smell mean they’re choosing bottled water for now.

The muddy water has made fishing, one of the town’s most popular pastimes and tourist draws, next to impossible. Those who’ve paddled Foster Reservoir in kayaks have been greeted by masses of dead fish, including the die-off of tens of thousands of kokanee earlier this fall.

“People are pretty upset by it,” Coleman said. “If this continues into the future, I think it will be devastating for the community.”

A surprising culprit: A plan to save wild salmon

The cause of Sweet Home’s fouled water is coming from a court-ordered plan meant to save endangered salmon.

In response to a lawsuit from three environmental groups, U.S. District Judge Marco Hernandez in 2021 ordered U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to undertake a series of actions meant to prevent the extinction of Upper Willamette River wild spring Chinook.

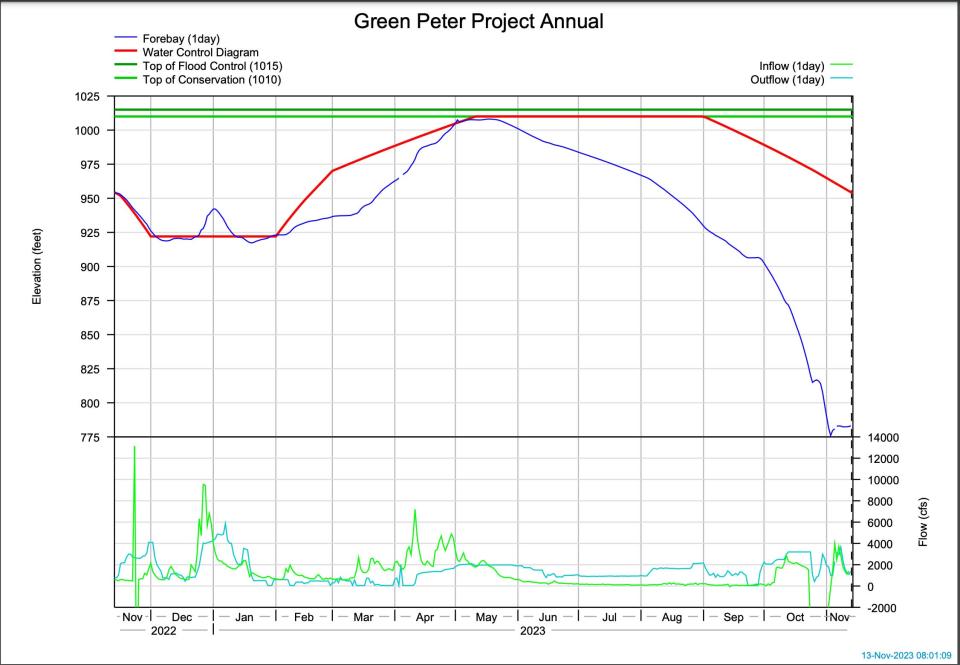

The most impactful of those actions was drawdowns. In this case, requiring the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to take Green Peter Reservoir, located about 10 miles northeast of town, to historically low levels. The reservoir was lowered all summer and this fall plummeted to levels not seen since the dam was constructed in 1966.

As the reservoir transformed back into a river, the water began flushing out mass amounts of built-up sediment into the South Santiam, Foster Lake and the main Willamette River. The amount of sediment in the water has reached 10 to 20 times its normal levels at times.

Drawdowns at Green Peter, along Lookout Point Reservoir to the south, are expected to keep the water muddy in the South Santiam, Middle Fork Willamette and mainstem Willamette rivers until at least Dec. 16, when the Army Corps will start to raise the level of the reservoirs. The Lookout Point drawdown has brought its own set of problems, including dried up wells that have required residents to pay nearly $30,000 to restore drinking water.

Mark Sherwood, executive director of the Native Fish Society, one of the groups that filed the lawsuit that led to the court order to draw down the reservoirs, said the turbid water should be temporary.

“In other cases where these drawdowns were used — and where they’ve been successful — we saw a spike in turbidity the first year and then it tapered off is subsequent years,” Sherwood said, citing previous experiences at Cougar and Fall Creek reservoirs.

Greg Taylor, supervisory fish biologist for the Corps in the Willamette Valley, said the muddy water may ease in the future, but it could still be an issue. It’s unclear what will happen, said Taylor.

Corps officials originally told the Statesman Journal and city officials that the drawdown wouldn’t impact drinking water. That has not ended up being the case.

"I don't think there was real understanding about the magnitude and duration of the turbidity (muddy water)," said Taylor.

But the Corps also pointed out they had no say in the matter. The court order was clear: drop the reservoir.

Why lake levels were dropped at Green Peter and Lookout Point reservoirs

The reason for such an extreme move, in a nutshell, is to help baby salmon migrate through dams.

The Army Corps is using trucks to move adult salmon above the dams, into high-quality spawning habitat of streams such as Quartzville Creek, the South Fork McKenzie and the upper Middle Fork Willamette.

After the adults spawn, juvenile fish swim downstream. Historically, when they hit the reservoir, they have struggled to continue through the dams because of the reservoir depth.

“Fish are surface oriented, meaning they live in the top 20 to 50 feet of the water column and they just don’t find those gates unless they’re closer to them,” Taylor said.

Short of expensive fish collection devices, the best option is for fish to migrate out through the gates or outlets low in the dams, environmentalists and Corps officials said.

That means dropping the water down. Way, way down.

The goal: restoring salmon runs in the Upper Willamette

Given time, the drawdowns should work to help restore wild salmon, said Sherwood.

When salmon reach quality spawning grounds above the dams, and juveniles can migrate back to the ocean, populations can rebound, he said.

Sherwood cited success in the Clackamas River, where improved fish passage systems in North Fork Reservoir — a fish ladder and slide —helped improve wild spring chinook runs to 3,125 fish per year over the past five years. The Clackamas system does not use drawdowns, however.

One place that has used drawdowns is Fall Creek Reservoir. It has seen an average of 350 wild salmon return, and numbers as high as 834 in 2020.

“If we get fish passage right, we really can restore wild spring chinook in the Willamette — this iconic Oregon fish. That would be a boon for every community in the Willamette Valley,” Sherwood said. “Drawdowns are the only way that's been shown to have good fish passage success at the large dams in the Willamette. The goal is building a tourism and fishing economy around abundant wild salmon and steelhead. We really can do it.

“But right now they’re in a lot of trouble. Time is running out for them and if we’re not careful, they could just blink out. We can’t let that happen.”

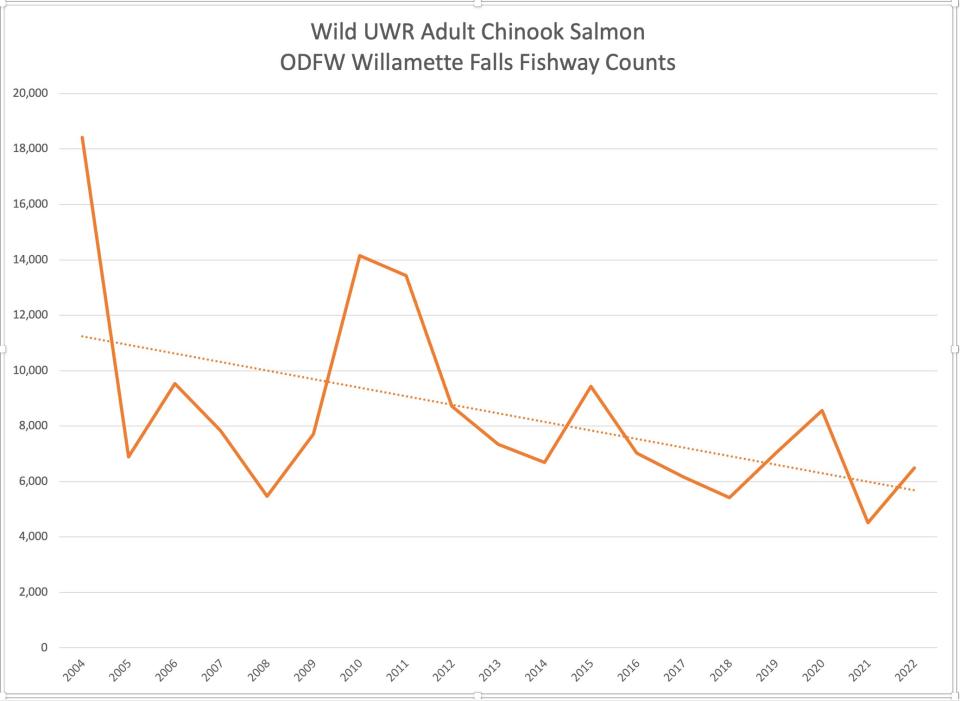

Wild spring Chinook, first listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1999, have seen numbers continued to decline. Their populations dropped to between 4,000 to 7,000 fish over the past five years in the Upper Willamette Basin, down from 18,000 in 2004.

That's brought an urgency to establish populations above the dams and led to the lawsuit and court-ordered drawdowns. But there also is no guarantee the drawdowns will work, as salmon runs are impacted by a host of issues ranging from ocean conditions to pollution to sea lions predation.

A pause on the drawdowns? Oregon politicians weigh in

Coleman, the Sweet Home mayor, is advocating for a “pause” on the drawdowns next year.

In addition to having a major impact on the town’s drinking water, economy and quality of life, she noted the impact on wildlife. In addition to documented die-offs of resident fish and fresh water claims, she said the habitat of protected species such as Pacific lamprey and Cope’s giant salamander is at risk due the high level of mud and sediment.

“If a logging company came in and had this much impact on water quality and wildlife, it would get shut down in no time,” Coleman said. “Why is this a different situation? It just seems backward.”

A pause in the drawdowns would require a court order, legal experts said. To that end, Oregon Republican Rep. Lori Chavez-DeRemer sent a letter to Judge Hernandez requesting “the federal court revisit the court injunction, and develop a better alternative at Green Peter dam to improve fish passage.”

She added that “this injunction is causing more harm than good.”

Oregon’s senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley also made statements supporting finding a solution, though it’s not clear what that would be.

“The drawdown of the reservoirs is creating a massive problem,” Merkley said. “This challenge needs an all-hands-on-deck approach. That’s why we are working with the governor’s team, USDA, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to find a solution.”

Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek's office added: “The Governor’s priority is to ensure that all Oregonians have access to clean, safe drinking water. Members of the Governor’s team are staying closely in touch with the congressional delegation, Army Corps of Engineers, and local leaders in the region to understand the impacts of the drawdowns and what options exist to support the impacted communities.”

Lebanon mayor Ken Jackola said he also supports a pause in the drawdowns.

But at the very least, Jackola said, the cities should get funding for their drinking water systems.

“If they’re going to force us to go through this, the federal and state governments need to ante up for these extra costs,” Jackola said.

Sherwood, with the Native Fish Society, said he understands the frustration of the people of Sweet Home and Lebanon, and also is lobbying state and federal officials for funding to help treat water in the short term.

“We strongly support relief for them,” Sherwood said.

Correction: A previous version of this story said North Fork Dam and Reservoir on the Clackamas River used drawdowns for fish passage. It doesn't. The dam has a fish ladder and slide for upstream and downstream passage. The Statesman Journal regrets the error.

Zach Urness has been an outdoors reporter in Oregon for 15 years and is host of the Explore Oregon Podcast. To support his work, subscribe to the Statesman Journal. He can be reached at zurness@StatesmanJournal.com or (503) 399-6801. Find him on Twitter at @ZachsORoutdoors.

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: Sweet Home, Lebanon grapple with drinking water amid dam drawdown