Mueller, a man of few words, may disappoint Trump impeachment advocates

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Robert Mueller is a man of few words. Once, when he was FBI director, he picked up complaints — passed along by his wife — that he was pushing his aides too hard. So, he called up Chuck Rosenberg, his chief of staff.

“How are you doing?” Mueller asked him.

“Fine,” Rosenberg replied. “What can I get you, boss?”

“Nothing,” replied Mueller, ending the conversation, satisfied he had done all he needed to do to check up on his overworked staff.

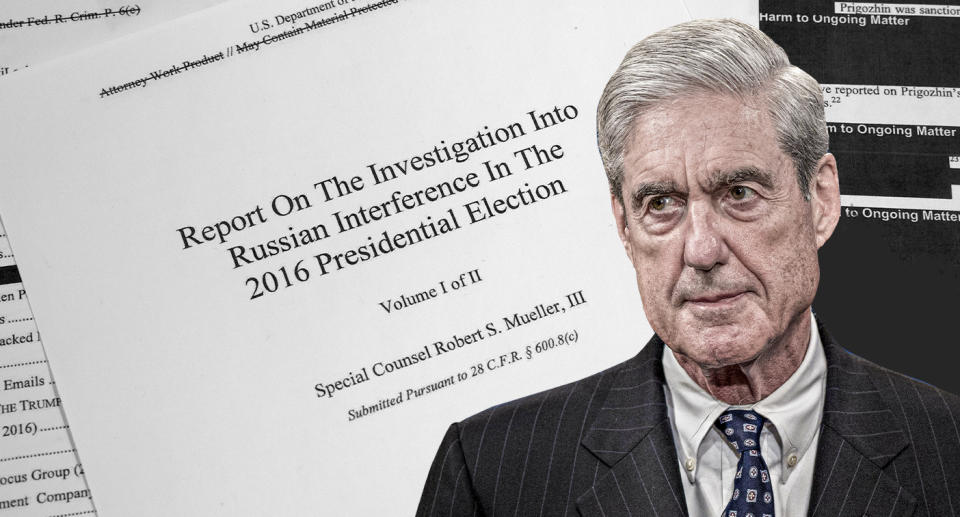

That exchange, recounted in “The Threat Matrix,” a penetrating book about the FBI by journalist Garrett Graff, is emblematic of the taciturn, strait-laced Marine who will take center stage Wednesday when he appears before the House Judiciary and Intelligence committees to testify about his landmark report on Russian interference in the 2016 election.

The hearings are being billed as a watershed moment in a political drama that has gripped Washington ever since Donald Trump was sworn in as president. Democrats clearly hope that simply hearing Mueller speak will give new life to a dry, dense 448-page report that they argue has damning evidence of presidential misconduct. “The Mueller book will never be read by most of the American public, but the Mueller movie will be watched,” Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., said when it was announced that Mueller would testify before the congressional committees.

But those who know him best say Mueller is unlikely to deliver — or say much, if anything — that will advance the cause of those advocating Trump’s impeachment. The 74-year-old former special counsel has shunned the public limelight for decades, rarely giving interviews or holding press conferences. When he was required to testify before Congress, Mueller would generally speak in clipped, stilted and legalistic terms, almost never straying from his written talking points. “A lot of people are going to be disappointed,” said one former FBI veteran when asked what to expect when Mueller, at long last, appears under the klieg lights.

To be sure, Mueller has pretty much telegraphed as much. “The report is my testimony,” he memorably declared in May when he made his only public comments about the investigation that the political world had been obsessing over for the previous two years. It is worth noting that Mueller — unlike special counsels or independent counsels in the past — said absolutely nothing public during the course of his probe. He never defended himself when Trump repeatedly derided his investigation as a “witch hunt” or attacked his staff members as “angry Democrats.” After Mueller delivered what was arguably his most important indictment — against Russian military intelligence officers for hacking the Democratic National Committee and delivering the stolen contents to WikiLeaks — it was then-Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein who gave the press conference detailing the charges. The noteworthy point wasn’t just that Mueller didn’t conduct the press conference. He didn’t even show up.

Moreover, a Justice Department official just made Mueller’s desire to stay as mute as possible a lot easier. In a remarkably broad letter, Associate Deputy Attorney General Bradley Weinsheimer gave Mueller strict guidelines he should follow when he testifies about his tenure serving as the Justice Department special counsel. Mueller should “not go beyond” the public wording of his report, Weinsheimer wrote. He should say nothing about redacted portions that may affect ongoing cases, such as the upcoming trial of Roger Stone, the president’s longtime political adviser. He must adhere to the department’s “longstanding policy” of not discussing “uncharged third parties” (read: Trump or members of his family). And perhaps most critically, the letter stated that Mueller should refrain from saying anything about the internal deliberations of his office — how and why it reached the decisions it made on the grounds that such matters could be covered by executive privilege, attorney work product and other potential legal bars.

What got less attention than the heavy-handed edict from the department was the predicate for the letter itself. It was Mueller who asked for it. On July 10, Mueller requested the department give him guidance on what he could or could not say to the committees. The unanswered question (so far) is whether Mueller feels unduly constrained by the Justice letter — or whether it was exactly what he wanted to give him the cover he needed to say nothing.

That said, there are legitimate questions that Mueller will be asked, and many will want him to answer regardless of where they come down on the impeachment question. First and foremost, is why he did not reach a legal conclusion as to whether Trump obstructed justice — a dereliction of his duty as a prosecutor, in the minds of many of his critics.

As is now well known, Mueller’s report documents 10 instances of potential obstruction. The most serious instances were Trump’s directive to White House counsel Don McGahn to call up Rosenstein and have Mueller removed for potential conflicts and, after this got reported months later by the New York Times, his instruction to McGahn to write a memo denying what the Times accurately reported. (McGahn refused both orders from the president.)

Mueller detailed other highly problematic instances — such as Trump’s directive to former campaign manager Corey Lewandowski to deliver a message to then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions to reverse his recusal from the Russia probe and then order Mueller to restrict the probe to “investigating election meddling for future elections.” (Lewandowski, like McGahn, balked — and there was no explanation of how the Justice Department special counsel was supposed to restrict his investigation into events that hadn’t yet happened.)

The Mueller report dwells at some length on preexisting Justice Department legal opinions that conclude that a sitting president cannot be indicted while in office. That will undoubtedly prompt Democrats to press Mueller hard on the fundamental question: Would he have recommended that Trump be indicted were he not president?

But the actual wording of Mueller’s report doesn’t suggest there is an easy answer to that question. It notes, for example, that “the evidence we obtained did not establish that the President was involved in an underlying crime related to Russian election interference.” While that does not preclude a criminal charge of obstruction — a defendant can obstruct an investigation into conduct that was personally or politically embarrassing even if it wasn’t criminal — it does make such an indictment less salable to a potential jury.

In the end, Mueller wrote in his report in one of its more ambiguous passages, he and his team did not reach a “traditional prosecutorial judgment” as to whether Trump committed a crime. The evidence they compiled “presents difficult issues that would need to be resolved if we were making” such a judgment, he wrote. Just what those issues are would be central to resolving the biggest issue of all for House Democrats: whether they should proceed to the impeachment of Trump based on Mueller’s evidence. If history is any guide, Democrats shouldn’t expect Mueller to make their job any easier.

_____