Multiple endangered whales found dead on nation's coasts, alarming conservation groups

At least seven endangered whales have been found dead or seriously injured, or gone missing since mid-December, including five North Atlantic right whales on the Atlantic Coast and two fin whales on the Pacific Coast, raising concerns among whale conservation groups, federal officials, and others.

"It's important to understand how whales are dying on both coasts, to understand risks and develop mitigation," said Regina Asmutis-Silvia, executive director of Whale and Dolphin Conservation USA.

Two of the dead whales – a right whale that washed up on Martha's Vineyard and a fin whale that washed up this week on the Oregon coast – were entangled in fishing gear, which federal officials, who are investigating the deaths, say is a leading cause of whale deaths.

"Any time a whale is entangled, we should be raising alarms because it shouldn’t be happening," said Ben Grundy, an oceans campaign director for the Center for Biological Diversity.

The Martha's Vineyard whale is one of two right whales reported dead since late January. The other was seen off the Georgia coast, east of Savannah this week. Sea Tow has been hired to try to bring that animal to shore on Thursday for examination. Both were females.

Feds: Entangling fishing rope came from Maine waters

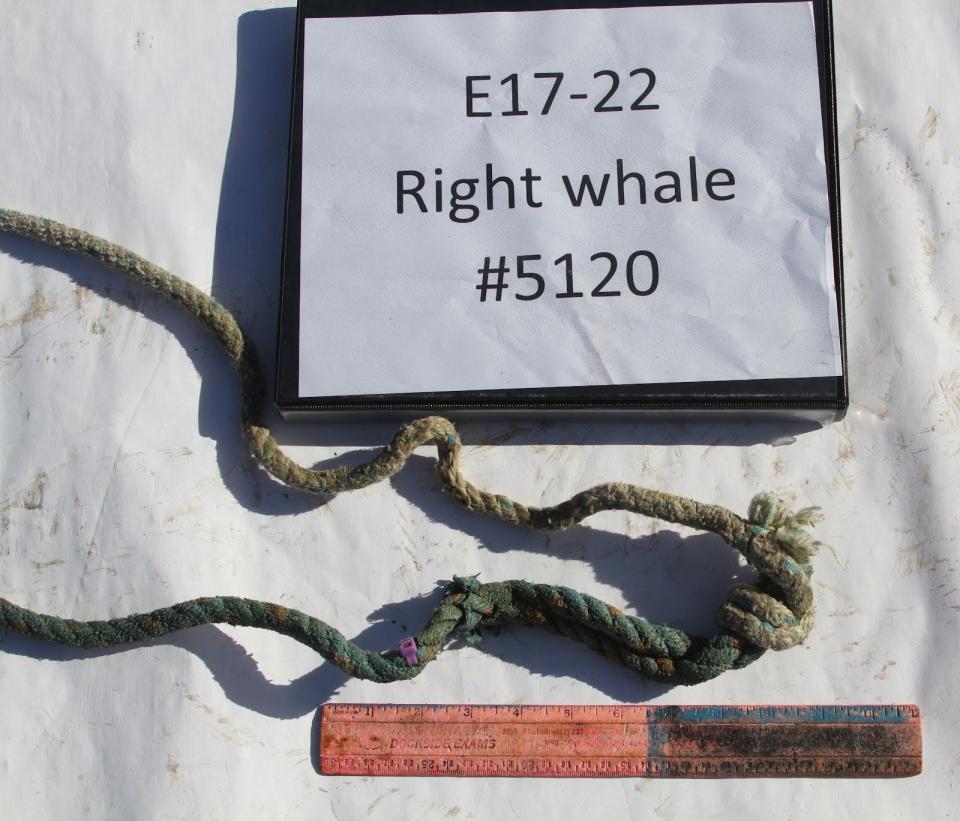

An examination of the entangling rope found on the right whale on Martha's Vineyard whale triggered an announcement from the National Marine Fisheries Service on Wednesday, as well as immediate responses from whale conservation groups and the fishing industry.

On Wednesday, the fisheries service said it had identified the rope as gear belonging to a crab pot or lobster pot in Maine state waters.

Rope had been wrapped around its tail for more than half the 3-year-old right whale's life, digging into its flesh to the point the tissue was growing over the rope long before it washed up dead in Edgartown. The rope was cut out of the tail during a necropsy, and while the final results of that exam are still pending, the fisheries service said the rope had purple markings that show it was from Maine.

Whale advocacy groups heralded that news saying it should end assertions by the state’s lobster industry that a dead whale had never been documented in fishing gear from Maine.

More importantly, said Asmutis-Silvia, the announcement proves gear marking can help scientists figure out where the animals are and when so rules can be tailored to individual areas rather than blanketed across an entire industry. “It’s not an issue of placing blame,” she said. “It’s so important to understand where this is happening, where the risk is.”

In defense of the lobstermen

A group of Maine officials, including U.S. Sen. Angus King and Gov. Janet Mills, said it was saddened by the whale's death but defended the state’s fishing industry, calling it a "vital part of our state's economy and heritage."

The group stated it was “unfortunate to learn that NOAA has concluded that rope embedded in the whale was consistent with lines used by the Maine lobster fishery.”

“We cannot, however, ignore the fact that entanglements in Maine fishing gear are rare – this is the first right whale entanglement with known Maine gear since 2004 and the first ever right whale mortality with known Maine gear,” the group stated.

The group stated they were awaiting the full results of the necropsy, and deflected to vessel strike, saying they remain a significant source of right whale deaths and chiding NOAA for failing to take more action on that.

The slow, painful death of a young whale

A timeline shows the dead, female juvenile whale on Martha’s Vineyard, No. 5120, was last seen gear-free on May 1, 2022, the day that Maine fishermen catching lobsters and Jonah crabs were required to start using purple gear markings in federal waters.

Here are other key dates in the whale's short life:

Jan. 19, 2021: No. 5120 was photographed as a calf with its mother, No. 3720, off the Florida/Georgia coast.

May 1, 2022: Seen gear free off Cape Cod.

Aug. 31, 2022: The calf was seen entangled in gear off the coast of New Brunswick, Canada. After that sighting, the whale was added to the government’s unusual whale mortality event, because of the seriousness of its injuries.

January 2023: the whale was seen several times in Cape Cod Bay, but rescue teams were unable to remove any of the rope wrapped around its tail.

June 2023: A survey team in the Gulf of St. Lawrence reported the whale’s condition had declined and the wounds from the rope appeared “more severe.”

NOAA’s finding that the rope was from Maine means the young whale went through Maine waters, got entangled, and then took the gear with her to Canada, Asmutis-Silvia said. As 5120 was growing, the rope was cutting deeper and deeper into her tissue as her body expanded, on a body part that she had to use constantly to swim.

“It had to be incredibly painful,” she said. “That means half her life was spent in pretty chronic pain.”

"Losing a female is devastating," she said. "It’s not just losing her, it's losing all the potential kids that she would have had."

Right whales on the edge

The difference between the fin whales and the right whales is that the latter is "on the verge of extinction and we know why and what those risks are," Asmutis-Silvia said.

Their population has plummeted 35% over the last 13 years. Nearly wiped out before hunting was banned in 1935, their numbers had rebounded to 481 in 2011, but then plummeted between 2013 and 2020 and now stand at an estimated 356.

The dead right whale found off Georgia on Feb. 13, was a juvenile female born during the 2022-23 calving season, to a whale named Pilgrim. She was seen off Melbourne Beach, Florida on Feb. 3.

Of the 17 calves born on the right whales' calving grounds off the Florida and Georgia coasts this winter, two are presumed dead after disappearing. Their mothers have been seen without them. A third calf, belonging to a female named Juno, was critically injured in a vessel strike.

It has been observed nursing, but its prognosis is poor, NOAA said.

The search for evidence

The finding on the Maine gear was the second time in four months that evidence surfaced of the critically endangered whales off Maine's coast.

A whale and seabird expedition chartered by Fluke Whale Tours last October took photos of a right whale mother and her calf in the Gulf of Maine, in a management area where lobster fishing with vertical lines is restricted between Oct. 1 and Jan. 31, said Zack Klyver, executive director of Gotham Whale. They shared photos with scientists at the New England Aquarium who confirmed the whale was a female named Spindle.

For years, whale experts challenged the assertion by Maine fishermen that there’s no proof whales were dying from lobster gear. But without marking, it was impossible to know where the animals got caught up in deadly, entangling gear, Asmutis-Silvia said.

Gib Brogan, a campaign director at Oceana, said the lobster fishery and Maine's delegation have "repeatedly denied culpability for whale entanglements, and they can no longer stand on this fantasy. "

"Maine needs to take responsibility for the harm it is causing to this critically endangered species and find a workable solution instead of denying facts and dragging its feet to make changes," Brogan said.

Maine’s lobstermen and women continue to “demonstrate a strong commitment to maintaining and protecting a sustainable fishery in the Gulf of Maine,” King and the others stated, adding the lobster fishers have invested in “countless precautionary measures to protect right whales, including removing more than 30,000 miles of line from the water and switching to weaker rope to prevent whales from being entangled.”

Fin whale numbers

The fisheries service examined the fin whale at Sunset Beach State Park in Oregon on Tuesday.

The service and the Seaside Aquarium urged people to leave the whale alone after the investigation was hampered by members of the public.

“Before authorized responders had a chance to examine the whale, someone removed the entangling gear,” the aquarium said. “It is extremely important to report strandings and to not interact or remove entangling gear from stranded animals.

The population of fin whales on the West Coast is an estimated 8,000, the Statesman Journal, part of the USA TODAY Network, reported. Three were stranded on the coast last year and two were stranded in 2022.

Contributing: Zach Urness, Salem Statesman Journal

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Endangered whales dying on both coasts as Maine death blamed on rope