Munich Olympics: Spitz gave 'greatest athletic performance' Indiana journalist ever saw

Editor's note: Bob Hammel covered the 1972 Munich Olympics for the Bloomington Herald-Telephone, by far the smallest U.S. newspaper to have a credentialed reporter there.

MUNICH — Germany returned to the Olympic Games for Munich 1972, the first time since the “Hitler Olympics” in Berlin in 1936. These Games were intended from the first planning session to show the world a new Germany, even though divided into East and West. From the start, the Olympic hosts’ emphasis was on peace. The prevailing color on all posters and banners, was a soft blue. The blue of an Alpine, Munich sky. The blue of peace.

It was my first Olympics, thus my first opening ceremonies. And this is what I wrote (everything italicized comes from stories I sent back to Bloomington in August and September 1972) about the Parade of Athletes at the traditional opening ceremony:

It sounds monotonous, this act of walking 8,000 people and 122 flags into a stadium, around the track, and parking them all in the grass. And then the thoughts start to flow:

There's Ireland out there, and Vietnam, two bleeding nations that found time for sports …

And there's Israel, getting a warm ovation and walking proudly into the land where its people once were brutalized …

There's Japan, a crushed ally of the home team in a world war this Olympic generation has heard about in history class …

War? A generation that has never seen a day without it put on this show that left more than one emotion-wrung spectator wondering: How can you hate anybody after seeing everybody like this?

That was on a Sunday.

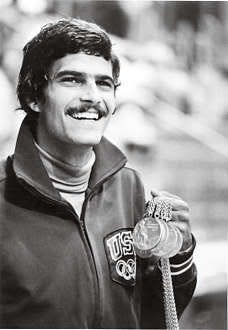

7 events. 7 golds. 7 records.50 years ago, IU's Mark Spitz became an icon.

In the five days to follow, Mark Spitz of Indiana University became the all-time champion in swimming gold medals at one Olympics. Spitz won five in the first five days of swimming and he was far from done.

And now it was September. Black September. The small Palestinian raiding party that was to make it Black already was assembling in Munich, but nobody in blue-skies, peaceful Munich knew. They called themselves Black September, and the name had no link with what they were to do two nights later: introduce America and most of the world to terrorism.

The win Spitz was waiting for

Spitz was in a three-day period between his finals, the last of which was a full day off. At the routine Thursday night press conference for medal winners, Spitz asked to be excused from questions so the spotlight could play on his three relay teammates “because this is their first gold medal.” (Two were IU teammates of his, John Kinsella and Fred Tyler.)

It was a wonderfully magnanimous gesture, but I knew from past interviews that winning the 100-meter butterfly that night was much bigger to him than he was indicating. That was the event he felt he owned, the one, he had told me in a Bloomington interview 18 months before, that “I've been swimming the most, and winning it the longest, more than any other event. It's just like my event.”

More in sports:IU tight end, Bloomington South grad James Bomba earns scholarship

He had lost in Mexico City by a half-second to American teammate Doug Russell, his only 100-meter butterfly defeat in a half-dozen years. When he lost, older teammates resentful of his cockiness had openly celebrated. All of that played into the emotional collapse that made him, for the rest of those games, a competitive shadow of the champion who had come in. In the eight-man finals of an individual event later at Mexico City, he finished last. Guaranteed: Mark Spitz, even in his tadpole days as a learning swimmer, had never finished last in an eight-man race. In 1971, sitting in a student's chair in that HPER classroom where he answered my questions one late-season day after an IU practice, he remembered that humiliation.

“I remember looking at Russell after the race. I knew how he felt. I had been there. You can't describe to a person who hasn't known the feeling what it means to be No. 1. Once you've had it, you can't settle for anything else, and you'll scratch and work and do whatever you have to do to beat the man in the lane beside you to get there. And if you were to ask me the same question after the Olympics, and I had won every race between now and then, I would probably answer the question the same way. Or if not, my biggest race would probably be in the same event at Munich.”

This was Munich. This was that race. And at that post-competition press conference, he hadn't said a word about how he felt.

I made tentative arrangements to see him on Saturday in Olympic Village for a 10-minute chat.

He didn't show. I was about to leave when someone said: “Spitz? I just saw him enter the hospital tent.”

Turned out he had felt a back twinge when his bumper car was hit as he was getting out in the Village's recreation area. He still had two events. I identified myself at the tent and asked an aide to go behind a curtain and ask if I could meet him later. The fellow had a dubious look as he left, but when he came back said, “Come through here.”

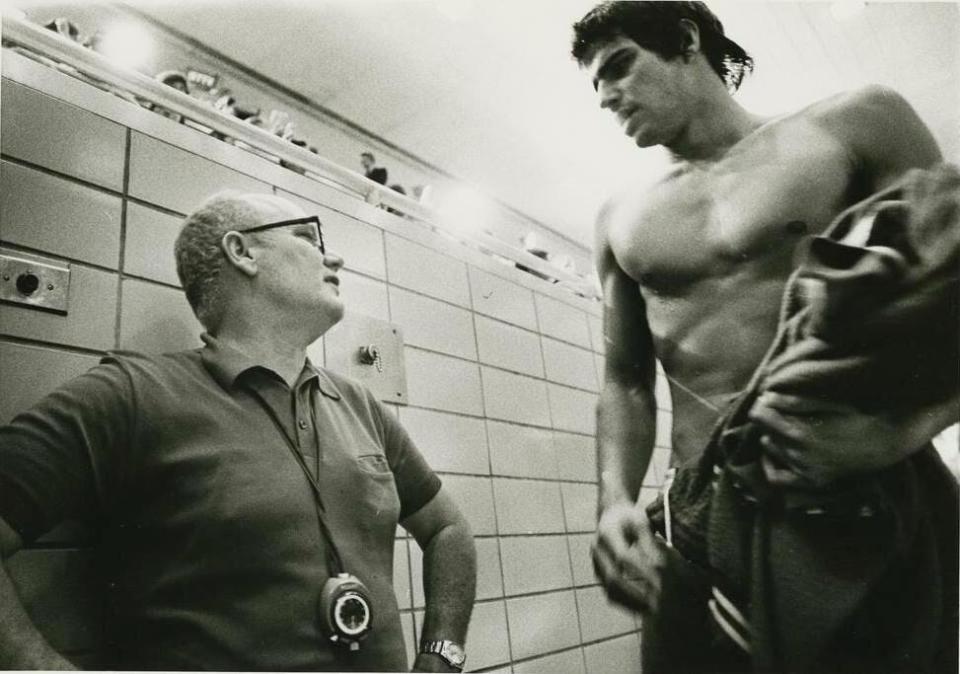

Spitz was stretched out on a table, a heat lamp baking the sore area in his back. He was stuck there for 40 minutes. Maybe a conversation with almost anyone would have seemed acceptable to him. And we started the only private interview he gave at the Games, because well before leaving for Munich, Doc Counsilman had told him not to do any. Any. And Doc was one man cocky Mark Spitz listened to.

But, he knew Doc knew me and …

I pulled out my notepad.

On Sunday, Sept. 3, back home, a long interview ran in the Sunday Herald-Times, starting on Page 1. It included:

“I could quit now and consider my Olympics a success. Winning the fourth gold medal to tie Don Schollander's record and then winning the fifth to break it – that was the big thrill to me. Everything after that is downhill.”

And the question came: In, say, 20 or 25 years, how would you like Mark Spitz the swimmer to be remembered?

“I have no control over that,” he said. “I'd like for what I've done to be remembered, but who knows?

“I don't think the public remembers Don Schollander … but everybody remembers Jesse Owens and Jim Thorpe.”

“Who knows?” he had said.

He was more prescient than he imagined. Black September was about to make Munich 1972 remembered for something far more historic than Spitz's remarkable run of golds.

Spitz was fine and fit the next day and he won his most challenging race, beating fellow American Jerry Heidenreich by .43 of a second, less than a stroke, to win his sixth gold in the 100-meter freestyle. Monday, Labor Day, he swam the butterfly leg as America won the closing 4x100 medley relay — for Spitz, seven events, seven gold medals and seven world records. It was the greatest athletic performance I've ever seen.

Read Tuesday's print or online editions of The Herald-Times for the second part of Hammel's recollections.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Munich Olympics 1972: Journalist Bob Hammel on Mark Spitz's feat