Murder. A conviction. An exoneration. Was evidence of another suspect ignored — or hidden?

Kolleen Bunch believed for more than two decades that her brother's killer was in prison.

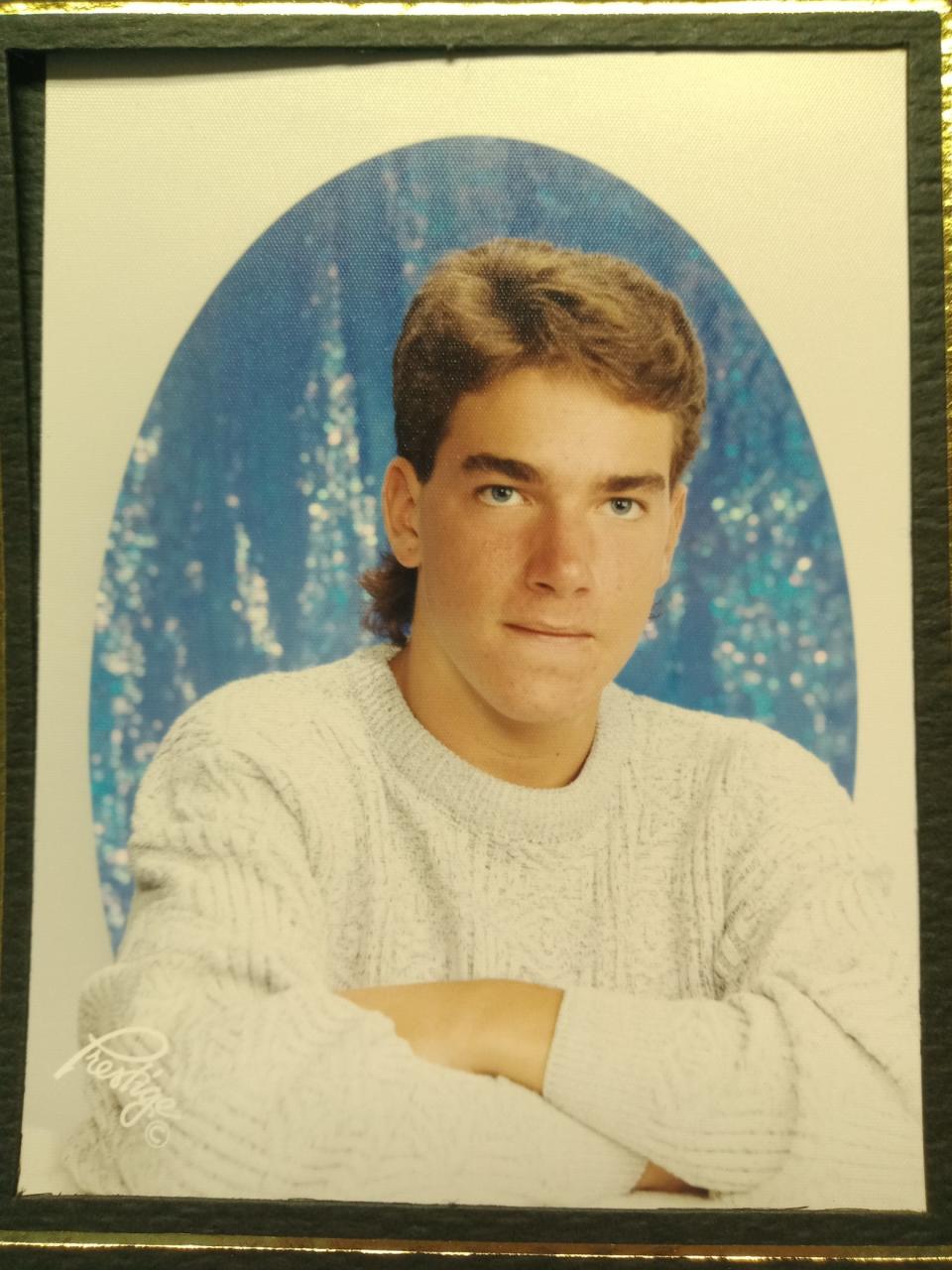

After all, Leon Benson was convicted and sentenced in 1999 for the murder of Kasey Schoen.

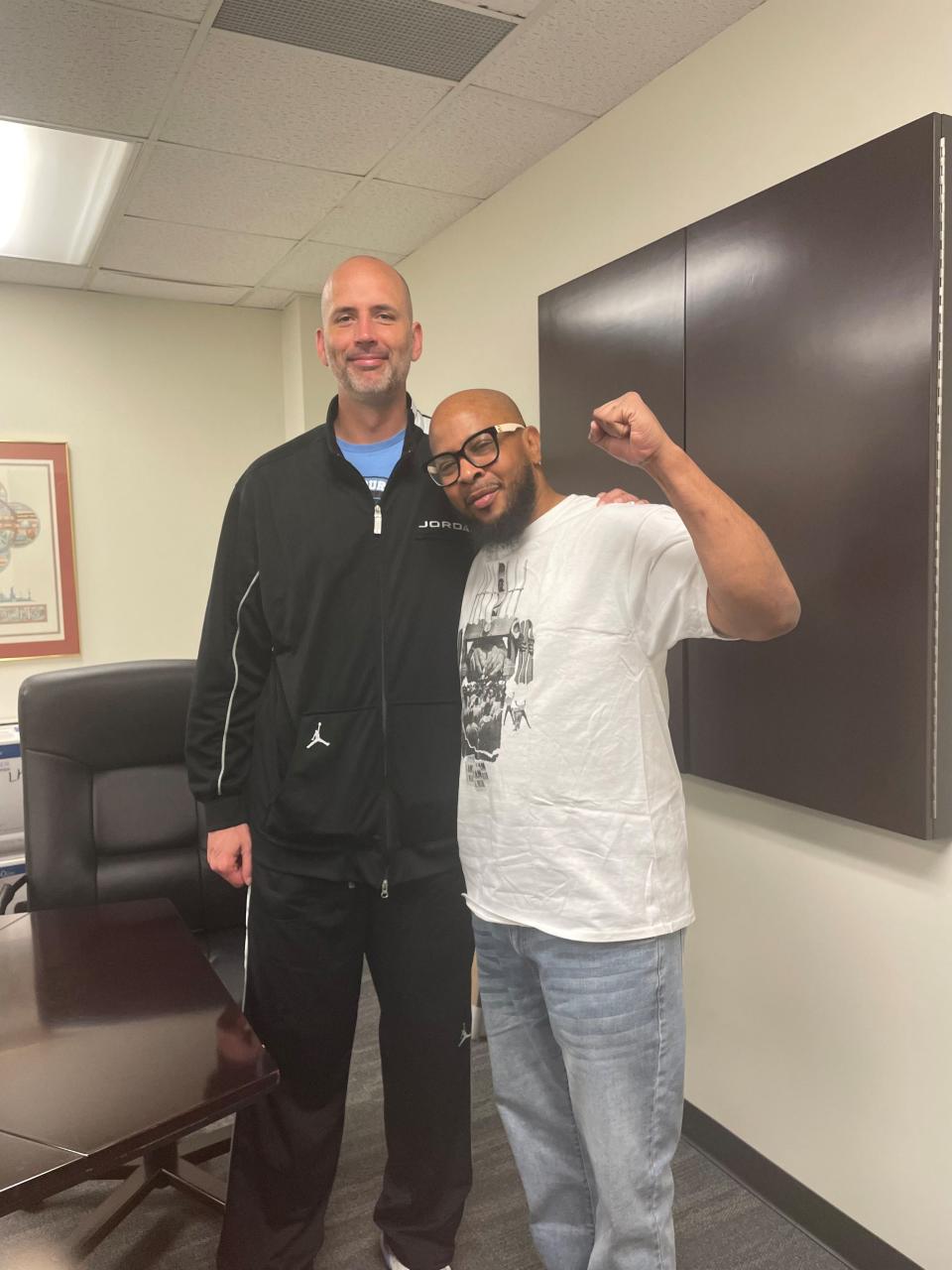

But prosecutors no longer believe they got the right man. And in March, Benson was exonerated by a judge and released after serving nearly 25 years in prison.

Now, evidence turned up in Benson's exoneration case points to another man as the possible killer. It is a man who at least two eyewitnesses reportedly saw shoot Schoen, according to police records. But recent court filings say Indianapolis police never shared that key information with the prosecution or defense.

'It is so surreal': After more than 20 years in prison, Indianapolis man exonerated in murder and set free

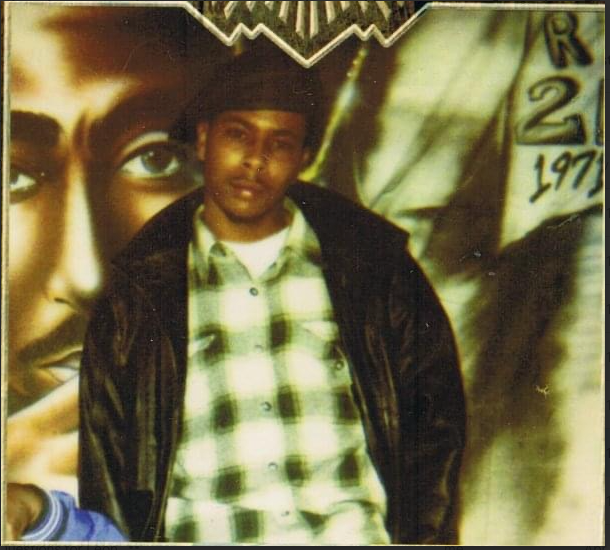

That other suspect, Joseph Webster, was never charged.

Over the next two decades, Webster continued to commit crimes until he got caught with drugs in 2017. That's when he became an informant to avoid jail time, according to documents, helping the FBI finally bring down a notorious drug ring led by Richard Grundy III. Police alleged the operation, dubbed the Grundy Crew, sold large quantities of marijuana, methamphetamine and heroin in Indianapolis ― and allegedly had ties to as many as 10 killings.

The fact Webster had been identified as a murder suspect 20 years earlier didn't come up at the Grundy drug trials. But his role in both cases is now under scrutiny.

Efforts by IndyStar to reach Webster were unsuccessful. As recently as last year, though, public records indicate he was living in Florida — a free man.

Richard Grundy III: How one notorious criminal career says so much about Indianapolis’ brutal violence

A drug dealer becomes an informant

The two unrelated criminal cases intersected in the fall of 2017, when Joseph Webster called his drug dealer to make a buy. It was the kind of call he'd made many times before. But this time it was directed by detectives who instructed him to buy three ounces of methamphetamine and some heroin. Police even gave the Indianapolis man $2,600 for the score.

"You got some 'old man' over there, Bro?" Webster can be heard asking the dealer, referring to heroin, on the recorded phone call. The dealer didn't have any heroin, so detectives instructed Webster to buy an additional ounce of methamphetamine.

Later, with a police "wire" concealed under his clothing, Webster met the dealer at an apartment building on North Meridian Street. The deal went down quickly, and Webster left with four ounces of white crystal-like meth.

Then, he walked a few blocks, making sure he wasn't followed, and met with a detective to hand over the drugs.

Webster described the Sept. 7, 2017, sting to jurors during a federal trial two years later. It was one of several monitored buys he made as an informant for the FBI during its investigation into the Grundy Crew.

To finally break up the dangerous criminal organization that had escaped prosecution for years, desperate law enforcement officials chose to rely ― at least partly ― on another dangerous criminal who had previously been identified as a suspect in a murder. Then they let him loose in exchange for his help.

Lara Bazelon, director of the University of San Francisco's Racial Justice Clinic, which worked to free Benson, said the handling of Webster revealed failures by law enforcement.

Criminal justice experts also say Webster's work as an informant did not follow typical protocols.

And an attorney for Grundy, now serving a life sentence, is calling for an examination of how much the government knew about Webster's criminal background when it turned him into an informant.

"I think they did not do their due diligence with regards to Joseph Webster," Bazelon said of the FBI. "And there was a lot about Joseph Webster they were happy not knowing."

Neither federal nor local law enforcement officials would say if they knew of Webster's possible ties to Schoen's murder when he became an informant.

The FBI and the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of Indiana, which prosecuted Grundy and his associates, did not answer questions about the circumstances of Webster's work as an informant. Instead, a spokesperson said: "The government takes its professional responsibilities very seriously and complied with them in this case."

Death of Joshua McLemore: Mentally ill man isolated in jail cell for 20 days without care before he died, lawsuit says

The Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department, which worked with the FBI on the Grundy investigation, did not say whether it informed the FBI that Webster had previously been identified as a possible suspect in a murder. "I don't know about all communication every officer had with the FBI or individual members of the public," said Lt. Shane Foley, an IMPD spokesman.

Foley said that IMPD's Unsolved Case Unit will now review Schoen's murder, but he declined to say if detectives are looking at Webster as a suspect.

Bunch, Schoen's sister, is understandably frustrated.

The man she spent the last 25 years believing killed her brother was set free. She's not ready to concede that Benson is completely innocent, but she also can't understand why police ignored evidence pointing to Webster.

"He should not have been out on the street to be an FBI informant," she said. "Great, he got some very bad people off the streets, but he was a very bad person before (the FBI) even came along. He's not any better than those he turned in."

Despite what she calls "compelling evidence" that Webster was Schoen's "actual killer," Bazelon said, Indianapolis detectives let him go more than two decades ago.

Back then, Webster was known on the streets by a nickname.

The Sarah Pender case: 'I deserve to be let home,' Sarah Jo Pender said. The man who prosecuted her agrees.

Eyewitnesses point to 'Looney'

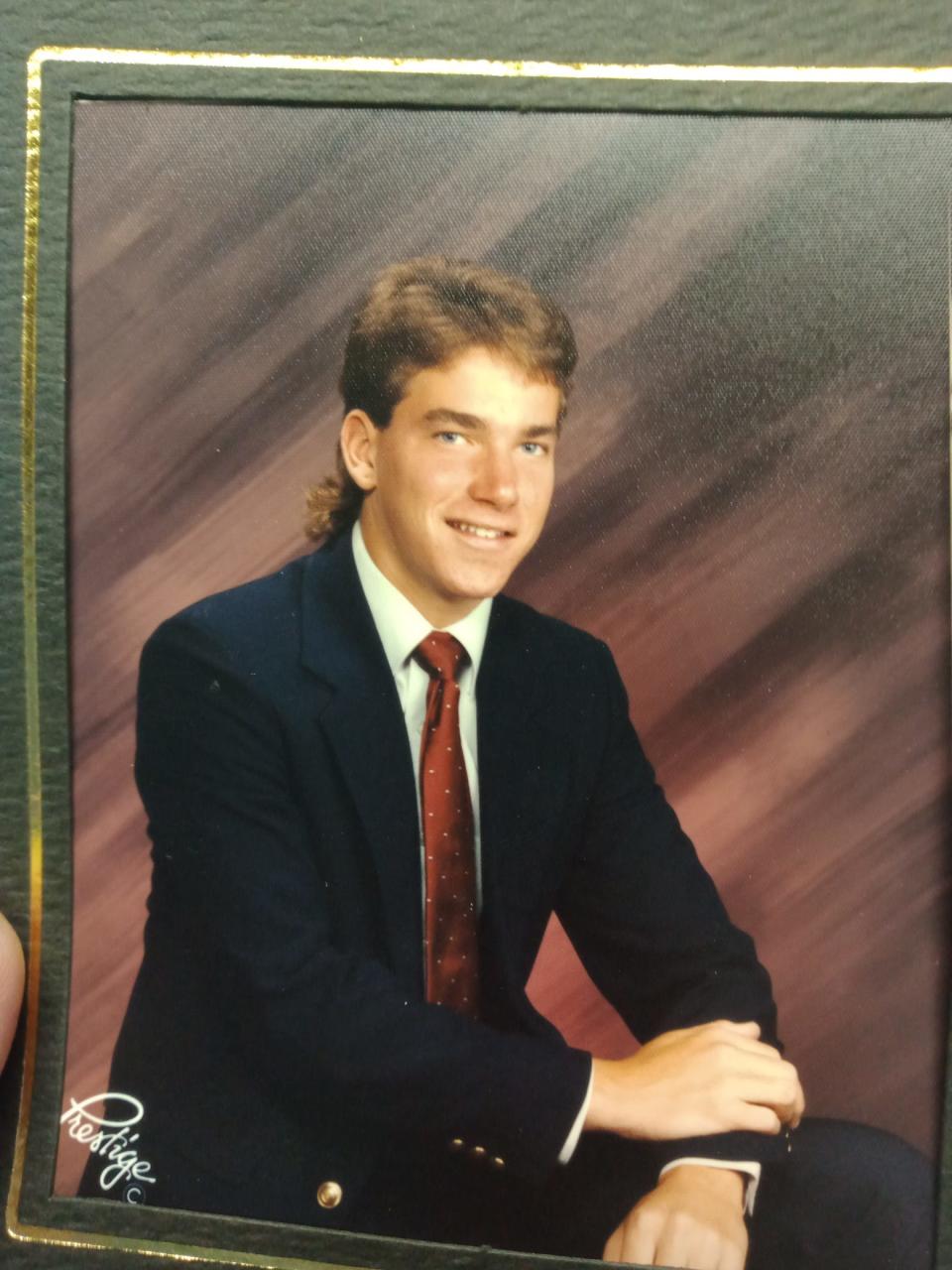

Schoen drove from Plainfield to Indianapolis the night of Aug. 7, 1998. Records show detectives suspected that Schoen, a closeted gay man, visited the Varsity Lounge, a now-closed gay bar just north of downtown.

At about 3:30 a.m. on Aug. 8, as he was sitting in his black Dodge Ram on Pennsylvania Street a few blocks from the bar, a man shot Schoen five times with a .380-caliber handgun.

A witness, who lived in a nearby apartment, later told police he saw the shooting and recognized the shooter.

The witness said he saw a man he knew in the neighborhood as "Looney" standing next to the pick-up truck, according to court filings. It was the middle of summer, but Looney was wearing dark pants with three white stripes on each leg, the witness said in a recent declaration recalling the events of that night.

Then, the witness said, Looney "took out a gun and unloaded the entire contents of the clip into the vehicle ... I heard somewhere between 5-8 shots."

It was the same man he ran into just hours earlier at an apartment building a short walk away from where Schoen later parked his truck, the witness told Indianapolis Police Det. Alan Jones, the lead investigator on the case, back in 1998. He said "Looney," wearing the same black pants with three white stripes, showed him his weapon, according to police records.

It was a .380-caliber handgun.

The witness later identified Webster, known in the neighborhood as "Looney," in a photo array.

Less than a month earlier, on July 12, 2008, an Indianapolis police officer arrested Webster outside another apartment building on Meridian Street, just around the corner from where Schoen was killed, according to a probable cause affidavit. In his possession were several small bags of cocaine ― and a .380-caliber handgun.

Jones later received a handwritten note from a fellow detective about another eyewitness. Det. Randy West, who died in 2016, wrote he learned from his confidential informant that a man named Eddie aka "Bo," who "runs with" Looney, "was present at shooting and saw Loony (sic) shot white guy in head."

Schoen was white. Webster and Benson are Black.

In a conversation last year with attorneys at the University of San Francisco's Racial Justice Clinic, Webster claimed he never met or did not know the witnesses who identified him. He admitted he used to sell drugs in the neighborhood where Schoen was killed but later backtracked, according to a record of the conversation.

Webster admitted he had been suspected of murders, including Schoen's, saying "maybe because I'm a non-likeable kinda guy."

He also seemed to admit he was nicknamed "Looney" because he was "silly" and "funny."

Ex-cop who didn't share evidence: 'That would haunt me'

The jury that convicted Benson never heard any of the evidence against Webster.

A recent reinvestigation by the Marion County Conviction Integrity Unit and the University of San Francisco’s Racial Justice Clinic found that Jones did not turn over 77 pages of his handwritten notes, including the note about Webster shooting "white guy in head," and the photo array in which an eyewitness identified Webster, according to court filings.

The detective also omitted paragraphs detailing his investigation into Webster from a probable cause affidavit he turned over to prosecutors that pointed to Benson as the killer, according to court filings.

IndyStar was unable to reach Jones. He left the police department and began working as a special deputy for the Marion County Sheriff's Office in 2008.

IMPD did not address a question about Jones' disclosure failures. But Foley, the spokesman, said the agency cooperated with the Marion County Conviction Integrity Unit's investigation.

In a recent declaration recounting the case, Jones said he considered handwritten notes as "work product." He said it was not his practice to turn those over to prosecutors. Instead, he turned over recordings or transcripts of interviews, which he said were better representations of witness' statements.

Jones did conduct a recorded interview of one of the eyewitnesses who reported seeing Webster, but that witness was never called to testify, the reinvestigation found.

Jones' statement also did not address why he did not turn over the photo array, or why he omitted details about Webster from the affidavit.

He said in the new statement he now has concerns about the case, particularly because Benson and Webster looked a lot alike. Jones is white.

"If it is proved that the wrong man was put in prison for the murder of Kasey Schoen," he wrote, "that would haunt me and I would want that mistake to be corrected."

Benson, who admitted being in the area that night, was convicted and sentenced to 61 years in prison. Another eyewitness identified him, giving detectives the same description of the gunman's clothing: black pants with three white stripes down the legs.

But Benson was wearing jeans that night, said another witness who told authorities he was with Benson inside a nearby apartment when they heard gunshots, according to court filings.

Again, the jury convicted Benson without hearing from this witness.

As Benson sat in prison, Webster went on to commit serious crimes.

How Webster became 'Individual 1' in Grundy case

Webster's long history of arrests dates to 1996, when he was 15. He was selling cocaine on the streets of Indianapolis by age 16, he told jurors during the Grundy trial.

A few months after Schoen’s murder, Webster and others beat up a man so severely that he required reconstructive surgery to fix his eye socket, according to charging documents. Webster was convicted of battery and sentenced to a year in prison.

In 2007, Webster’s wife told police he slapped her several times in the right arm. As she was calling 911, Webster snatched the phone from her and threw it across the room. He then grabbed her by the hair and punched her several times, according to a police report.

Then, he choked her until she passed out, she told police. She was 10 weeks pregnant.

The Herman Whitfield case: Why it can be an uphill, politically difficult battle to prosecute police officers

Webster pleaded guilty to criminal confinement and domestic battery. He was sentenced to nearly nine months in jail and two years of probation.

In August 2017, an Indianapolis police officer pulled him over while he was in possession of methamphetamine, a loaded gun and $600 in drug proceeds. Already a convicted felon, Webster was facing a potentially long sentence.

But he was never charged.

Instead, IMPD offered him an opportunity to cooperate with the FBI's investigation of the Grundy Crew, Webster testified during the Grundy trial.

He agreed, Webster told jurors, to "keep myself out of jail."

The FBI then moved him out of state and paid for nearly $8,000 in hotel stays, gas money and utilities. Local officials even threw out his traffic tickets, he testified.

Two days after he was pulled over, Webster orchestrated the first of eight drug buys for the government.

His testimony suggests he had the street reputation to pull it off, having known one of Grundy’s associates for years.

His cooperation came as the Grundy Crew nearly slipped out of law enforcement’s hands.

Richard Grundy III: How fake witnesses, exposed surveillance operation unravel Grundy murder investigation

By that summer, the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office’s high-profile case against the Grundy Crew had fallen apart. Problems with evidence and witnesses plagued the prosecution, and Grundy ― the drug kingpin who was originally looking at life in prison for allegations including murder and several other charges ― pleaded guilty to a single felony charge of dealing marijuana and walked out of a Marion County courtroom, basically a free man.

But federal investigators ― partly with Webster's help ― were still watching him and his crew.

On Nov. 13, 2017, Webster orchestrated his final drug buy for the government.

A week later, federal prosecutors announced the result of Operation Electric Avenue, a joint investigation by the FBI, IMPD and other local, state and federal agencies. Grundy and about two dozen others were indicted, this time on federal charges.

The testimony of "Individual 1," as Webster was identified in the indictments, was key in convicting Ezell Neville, who prosecutors said was Grundy’s principal distributor of methamphetamine. Neville was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

"It’s ironic, to say the least, that the FBI used Webster as a key witness in taking down a member of the Grundy Crew," Bazelon said, referring to Neville. "That man is serving 30 years for drug crimes while Webster is a free man."

And his road to becoming "Individual 1," experts say, was out of the norm.

A 'handshake agreement'

Normally, informants who are facing serious charges of their own reach a plea deal with the government outlining lesser charges in exchange for their cooperation.

Even in cases when the government decides to forego charges, there still must be a written record outlining how and why they became an informant, said David Weinstein, a former federal prosecutor in Florida who handled narcotics cases.

"All of that information," Weinstein said, "has to be provided to the defense."

None of these appear to have happened in Webster’s case. There was no written cooperation agreement or a plea deal, according to Bazelon, who looked into the Grundy case as part of her team’s reinvestigation of Benson's conviction.

"From my perspective as a former federal public defender who has represented clients who turned state’s evidence like Joseph Webster, the federal government’s handling of him was unusual," she said.

Richard Grundy III: How the bloodshed continued after Richard Grundy III got out of jail

A person familiar with the Grundy case likened Webster's cooperation with the government to a "handshake agreement," and said it wasn't until Webster testified that he revealed he agreed to cooperate in exchange for zero charges.

"If my memory serves," the person said, "he was the only cooperating witness who walked in and out of the front door of the courtroom, and who testified in street clothes."

Kenneth Riggins, who represented Grundy during the trial, said Webster's testimony was critical in proving the drug conspiracy. He said there needs to be "further analysis" of what prosecutors knew about Webster's background, and when they knew it.

Family left with anger and questions

Schoen was the youngest of six siblings in a family that has seen one tragedy after another.

Five years after Schoen was killed, his older brother committed suicide. The reason was a combination of things, said Bunch, Schoen's sister, but the murder "weighed heavily on him."

"He was the baby of our family, so he was spoiled by all of us," Bunch said of Kasey. "He loved to do things with everyone. He was a hard worker. He took care of our mom, if she needed it, and our grandmas, if they needed it."

The news of Benson’s release brought mixed emotions to Bunch. He may not have pulled the trigger, but she remains doubtful he’s an innocent bystander.

Still, she said, he’s done enough time.

Her theory is that her brother was killed because he was gay. But there’s no evidence that detectives meaningfully investigated that possibility, either.

The realization that Webster has been able to live his life as a free man fills Bunch with anger and leaves lingering questions.

"Where I am at about Joseph Webster is why did Det. Jones hide all this information?" she said. "There is some reason for him to have done that when his own police officers are telling him this is what they’ve heard. Why did he not push it any further?"

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Leon Benson, focus of 'Suspect' podcast, spent 20 years in prison