Murder most foul: The killing of Christopher Marlowe

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It’s the evening of 30 May 1593 and a young Will Shakespeare is about to become England’s greatest living dramatist because his greatest rival, Christopher Marlowe, is losing a knife fight in a boarding house in Deptford. When the blade of a twelvepenny dagger enters Marlowe’s skull two inches above his right eye, it penetrates his brain to a depth of two inches, putting an instant full stop to the fevered imagination that has captivated the Elizabethan stage.

Christopher Marlowe is dead. Three blood-spattered men stand over his body. An army of historians would love to witness the conversation that is about to take place between Ingram Frizer, Nicholas Skeres and Robert Poley because it would illuminate the murky underworld of Elizabethan espionage; there can be little doubt that – just like his killers – Marlowe was a spy.

Had this killing occurred a year ago it’s likely that Frizer, Skeres and Poley would be facing disaster. Marlowe had enjoyed the protection of the most powerful men in England but in recent weeks and months he has suffered a spectacular fall from grace and favour.

At the time of his death, Christopher Marlowe had been awaiting trial on charges of atheism – a crime serious enough to lead to the torture rack and the gallows. Marlowe – once a prized intelligence asset – had become an embarrassing liability.

If they can hold their nerve and get their story straight, Frizer, Seres and Poley realise they are likely to walk away as free men. And the coroner, William Danby, does indeed accept their version of events. Having met at the house at 1am on Wednesday, 30 May, the four men spend the day together, lunching before taking a tour of the gardens and supper. At an unspecified time in the evening, the men argue about who should pay the bill for the day’s meals, Marlowe rises from the bed where he’d been resting, seizes Frizers’ twelvepenny dagger and uses its handle to gash Frizer about the head and face. Poley and Skeres intervene and during the struggle to regain control of the knife, Frizer administers the fatal wound.

Marlowe is buried in the churchyard at Deptford and within weeks Frizer’s mitigating plea of self-defence is accepted and he receives a royal pardon and there – officially at least – the matter rests.

If any of Marlowe’s friends suspected premeditated foul play they would have known better than to have voiced those concerns openly because London is known to be a seething mass of paid informers, snoops and spies employed in an impenetrable web of “government service”.

Historians compare the paranoia of Elizabethan England to that of the McCarthyite red scare in 1950s America. Just as America feared communists as “the enemy within” preparing the way for Soviet invasion, Queen Elizabeth’s police state saw Catholic plots everywhere and with good reason.

In an era when social aspiration is seen as a vice, Marlowe’s ‘heroes’ are charismatic overreachers driven by vaulting ambition and a contempt for authority

As a reformed protestant nation, England was isolated in a Europe dominated by its Catholic superpower Spain. The Spanish armada may have failed but Catholic insurgency was a live threat as Robert Catesby’s gunpowder plot would demonstrate a decade later.

Spying was a labour intensive, growth industry where the state used an irregular army of informers to keep track of hundreds of people suspected of papist sympathies.

Information was such a valuable commodity that after the death of Elizabeth’s spymaster, Francis Walsingham Lord Burghley and the Earl of Essex even set up rival intelligence networks which spied on each other.

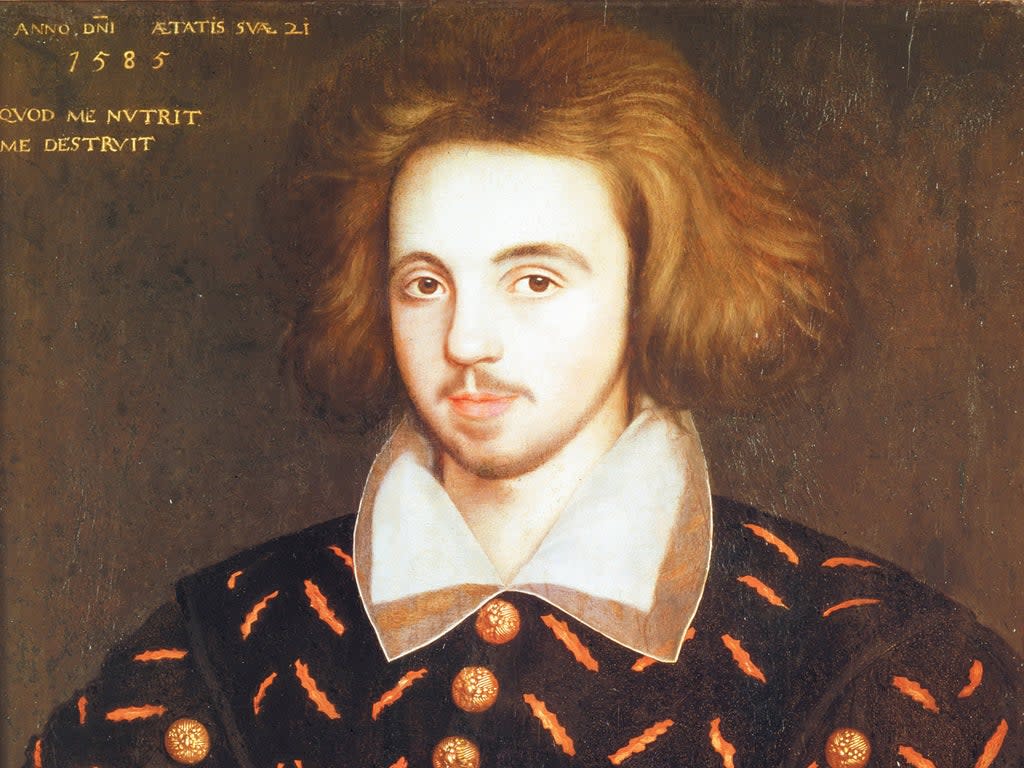

Religion loomed large in the life of Christopher Marlowe. Born under the shadow of Canterbury Cathedral, even Marlowe’s scholarship to Cambridge came with protestant strings attached. In return for their education, Archbishop Parker scholars were expected to enter the clergy upon graduation but Marlowe clearly wasn’t cut out to be a man of the cloth.

Marlowe not only fell in love with theatre while at university but also opted for a more dangerous form of role-playing. Like so many modern day spies, Marlowe was recruited while studying at Cambridge.

Mysterious gaps in the buttery book – the log of students’ food expenses – record Marlowe’s lengthy absences from Corpus Christi college from 1584 onwards when he should have been completing his studies for his masters’ degree. On return, Marlowe the son of a shoemaker and impoverished scholarship boy seemed unusually flush with funds.

In 1587 the university attempted to block Marlowe’s graduation providing the rather euphemism explanation he intended “to go to Reims” after graduation.

Reims was the town in northern France where a Catholic seminary exerted a gravitational pull on earnest young English men intending to defect to Catholicism and take holy orders.

In an extraordinary intervention, the privy council – the highest power in the land – wrote to the university reassuring them that while at Reims, Marlowe had been engaged in “matters touching the benefit of this country” and had “done good service” – the clear implication being that Marlowe had posed as a Catholic convert to gather intelligence on Catholic converts and potential enemies of the state.

Thanks to his friends in high places, Marlowe promptly received his MA. As an experienced field agent, skilled in Catholic counter insurgency, it’s likely that Marlowe continued to serve in the shadowy world of government service when he left Cambridge for London to make his way as a celebrated playwright and poet.

The security services viewed the burgeoning theatre community as an iniquitous den of radicalism and freethinking. Moving in those circles, there’s no doubt that Marlowe would have been a valuable asset. His friendship with Lord Strange and Sir Walter Raleigh – known radicals and free thinkers – would surely have been of interest to his part-time employers.

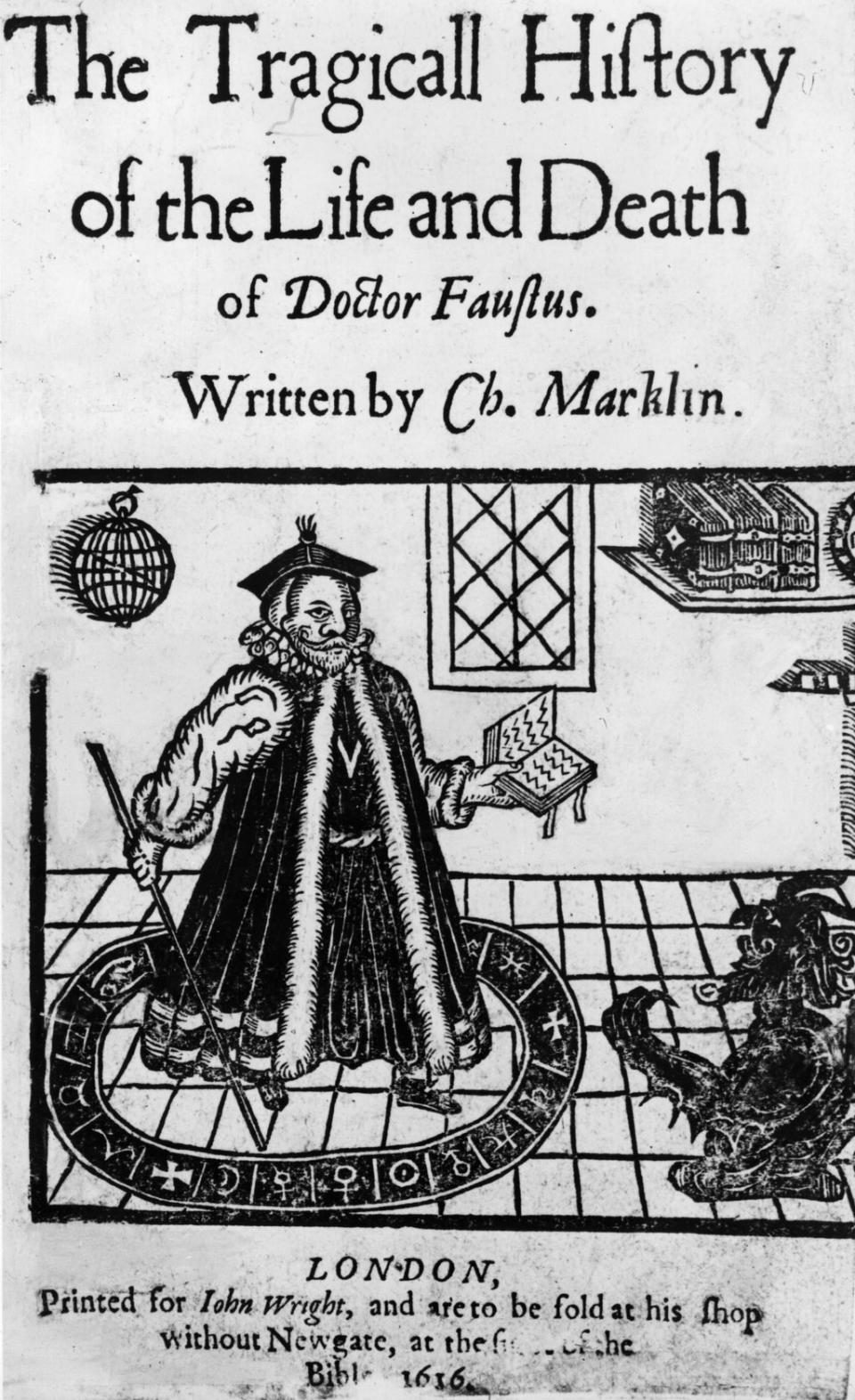

But his earliest successes on the London stage reveal Marlowe’s confused and confusing relationship with the establishment. In an era when social aspiration is seen as a vice Marlowe’s “heroes” are charismatic over reachers driven by vaulting ambition and a contempt for authority.

The most outlandish theory is that Marlowe didn’t die at all but was spirited out of the country to safety in Europe where he would secretly author the works falsely attributed to Shakespeare

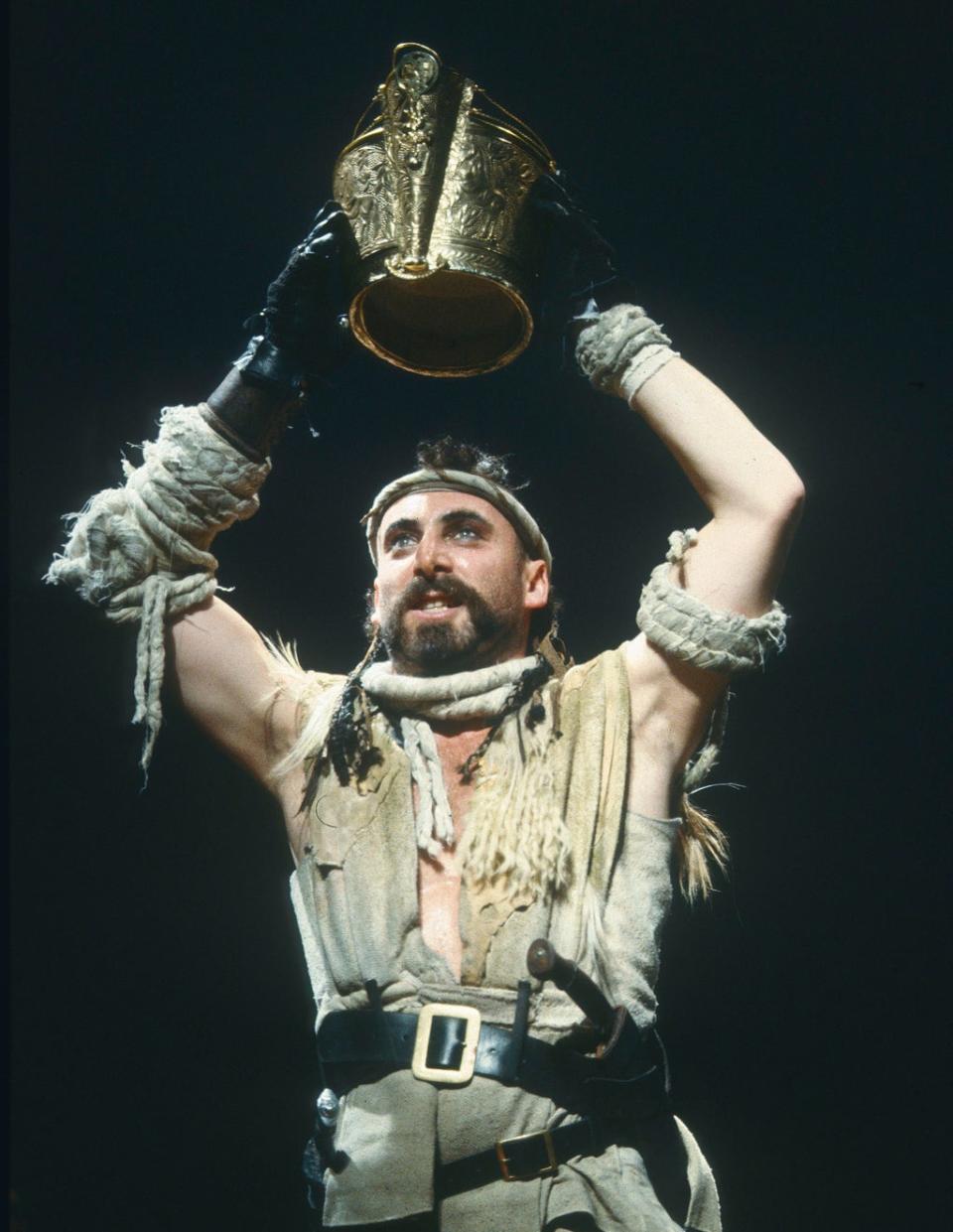

Marlowe’s mighty Tamburlaine rises from the status of a lowly shepherd possessed by his quest for world domination. His quest to become king of the world drives him to invade, Persia, Turkey and Europe. In one scene, Tamburlaine enters the stage in a chariot pulled by conquered kings. Another deposed monarch is caged to serve as a footstool.

Tamburlaine was such an enormous commercial success that it would spawn a sequel and become a byword for an irrepressible rise, a force that can not be constrained. In an era of government censorship when theatre audiences were populated by spies tasked with monitoring audience reaction for signs of potential uprisings, Marlowe was playing a dangerous game.

And yet as late as January 1592, Marlowe could still count on Privy council support to extricate him from his misadventures. When he was arrested in Flushing in the Netherlands for coin counterfeiting he was deported and faced serious charges of treason but again a privy council directive maintained that he had been “on service”.

But in the year before his death concerns must have grown about Marlowe’s reliability as an asset when rumours about his alleged atheism became impossible to ignore.

In the foreword to The Jew of Malta, first performed in early 1592 Marlowe uses Machiavel as a mouthpiece to denounce religion as instrument of social control. “I count religion but a childish toy. And hold there is no sin but ignorance. I am ashamed to hear such fooleries.”

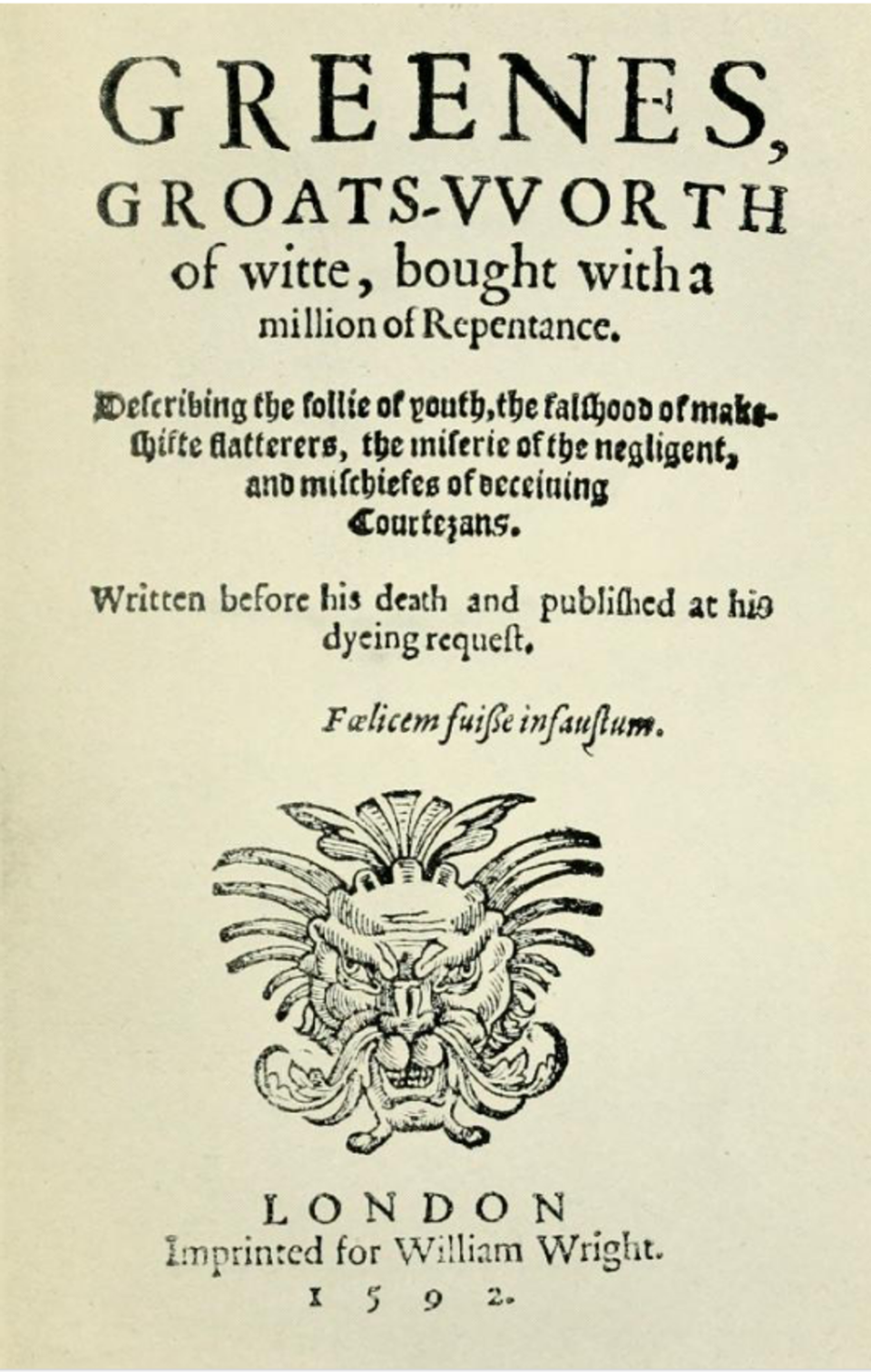

Marlowe’s rumoured atheism was so widely circulated that it featured as an incendiary accusation in the famous pamphlet that was published in September 1592. Alongside Shakespeare, Marlowe was libelled in Robert Greene’s Groat’s, Worth of Witte. While Shakespeare is attacked as an “Upstart Crow” Marlowe is denounced as an atheistic follower of Machiavel.

In the weeks before Marlowe’s death the suspicion must have been growing that like so many counterintelligence officers in the field, Marlowe had gone rogue.

In March 1593, the first hard evidence emerged against Marlowe. An investigation into Richard Cholmeley implicated Marlowe as an atheist, claiming he had even delivered a lecture to a gathering of free thinkers and radicals.

But it was concerns over civil unrest that precipitated Marlowe’s fall. In April, the first placards begin to appear in London streets inciting violence against protestant immigrants from Holland. The Privy Council were sufficiently concerned to set up a committee to investigate the “libels”, which were seen as a serious threat to law and order.

On 5 May another libel inciting violence towards Dutch refugee protestants is pinned to the Dutch church on Broad Street. It makes several references to Marlowe plays and is signed Tamburlaine.

The authorities were finding it difficult to disentangle anti-immigrant xenophobia from Catholic mischief and act with an urgency that suggests that they were afraid of losing control of the febrile London streets.

On 12 May, the authorities raid the home of Thomas Kyd, a fellow playwright and Marlowe’s former roommate.

Incriminating documents are discovered that deny “the deity of Christ”. The papers suggest that Jesus had a homosexual relationship with John the evangelist and that Moses was a mere conjuror. They also contain the infamous phrase “All who love not tobacco and boys are fools” Under torture Kyd denounces Marlowe as an atheist and the owner of the documents.

Marlowe is arrested and brought before the Privy Council on 20 May on charges of atheism. He is bailed but obliged to report to the court each day.

On 27 May, Richard Baines, former colleague in the intelligence services, brings a note to the attention of the Privy Council describing Marlowe’s blasphemies in more detail. Three days later, for reasons that have never been entirely clear, Marlowe finds himself in Deptford with three intelligence colleagues and soon afterwards he is dead.

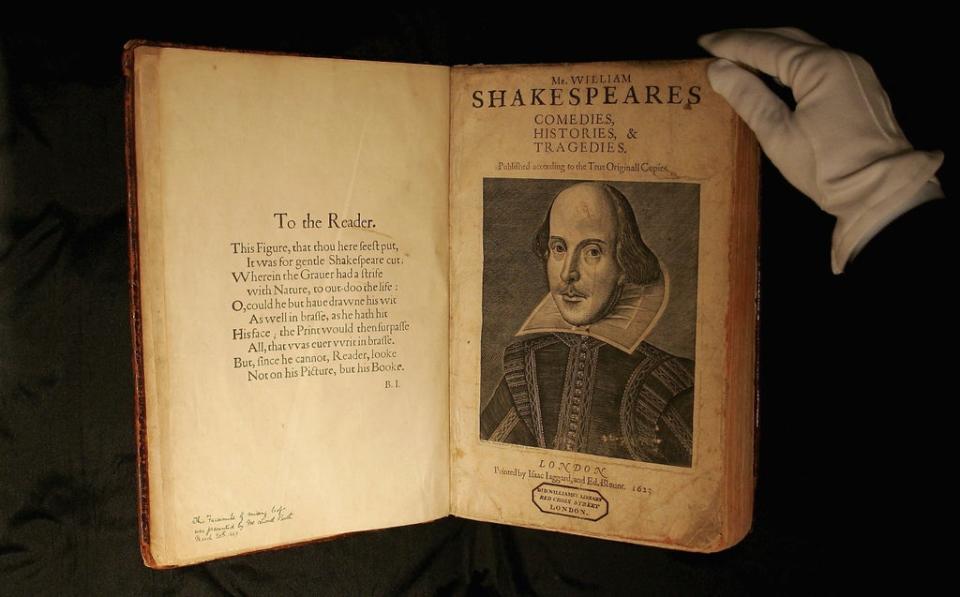

It’s a well worn story where the gaps in our knowledge outnumber the facts. It’s easy to see why it’s become such fertile ground for conspiracy theories. It’s likely that Marlowe would be interrogated under torture on those charges of atheism. Were the security services concerned about what he might reveal in extremis? Was he killed because of his refusal to give evidence that Sir Walter Raleigh was an atheist? Was he simply executed because patience had worn thin? The most outlandish theory is that Marlowe didn’t die at all but was spirited out of the country to safety Europe where he would secretly author the works falsely attributed to Shakespeare.

But perhaps wild-eyed theorists should remember that cockups are far more common than conspiracies and that even professional liars like Frizer, Skeres and Poley tell the truth sometimes. After all, if it had been their intention to assassinate Marlowe, that could have been more effectively accomplished elsewhere in anonymity.

Mercutio’s death is traumatising but profoundly moving, almost as if Shakespeare is giving London’s theatrical community the chance to make a fond farewell to their flawed but inspirational friend

In fact, the official version of events would have rung true for those who knew Marlowe’s character and circumstances well. After a day’s drinking, four young male colleagues who aren’t particularly enamoured of each other find themselves on a “works do” – they fall out and fight over money.

When it came to fatal fights over small sums of money Marlowe had plenty of form. Marlowe and fellow playwright Thomas Watson had killed a William Bradley in a fight over an unpaid debt. Marlowe had been incarcerated in Newgate prison for 12 days in 1589 before his mitigating plea of self-defence had been accepted. And Marlowe had also been bound over to keep the peace after another knife fight in Canterbury just a few months previously.

A picture emerges of a rash and impulsive young man querulous in drink. But poverty is the singular recurring theme in the life of Christopher Marlowe. From his scholarship days at Cambridge, Marlowe – the son of a shoemaker – certainly mixed with the wealthy and powerful but never possessed property or significant resources of his own.

His status as the most successful playwright of his generation would have counted for little. Marlowe was part of that first wave of professional playwrights who died in poverty because they hadn’t yet become shareholding partners in the companies that performed their plays – the business model that would allow Shakespeare to prosper in later life. Even the modest income Marlowe derived from the theatre was denied by a plague outbreak that kept the theatres closed for most of the last two years of his life.

Marlowe knew fame and infamy but never fortune. The coin counterfeiting escapade in Flushing is likely to be just another get rich quick scheme that backfired. Wealthy patrons might help keep creditors at bay, temporarily but Marlowe was part of the Elizabethan precariat which explains why he remained in the occasional employ of the security services. Espionage wasn’t a glamourous game played by dilettante gentlemen; it was poorly paid, casual work that brought you into contact with the sort of low company that Marlowe was keeping that day in Deptford.

Picture the injustice of it all. The malcontented Marlowe – a genius with the finest education money could buy, born into a stratified society engineered to prevent bright young men from rising. He has mixed with the rich and powerful and now denied their company facing, at best, ignominy and disgrace. At the age of 29, Christopher Marlowe is no longer a Tamburlaine-like climber; he is trapped in a dingy room, hungover listening to the laughter of the colleagues he detests as they gamble at backgammon. Perhaps from time to time, they jeer him – the former golden boy fallen on hard times. Marlowe is already out of the game nursing losses he can ill afford when it becomes clear Skeres, Frizer and Poley intend to stiff him for the bill too. As he rises from the bed to take issue with this final insult, they add the final injury too.

It’s unlikely that the intelligence community would have mourned Marlowe’s passing but it’s London’s close-knit world London’s theatre community world certainly have grieved the loss of such a leading light.

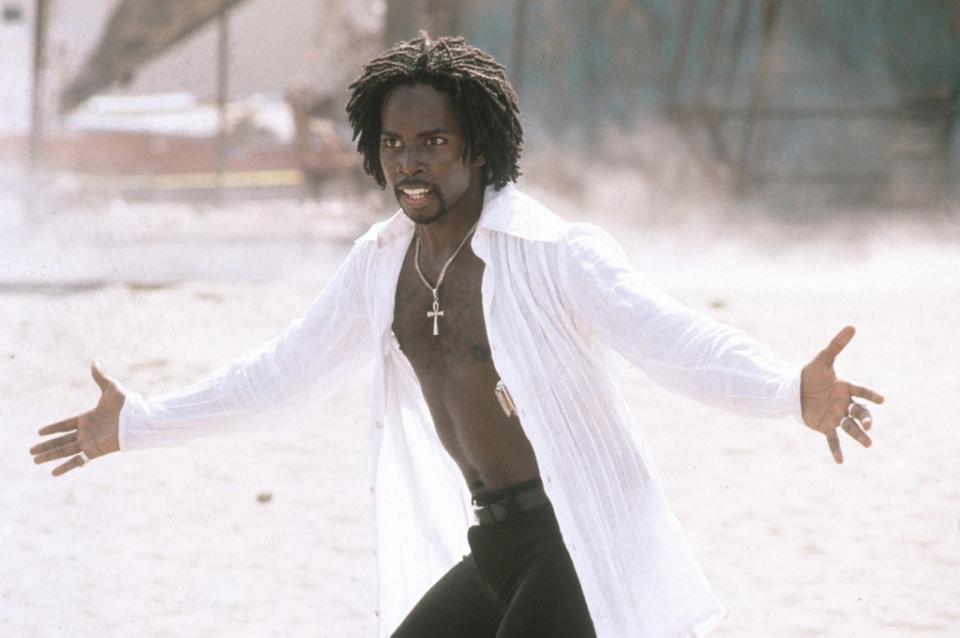

Marlowe’s violent death has launched a thousand wild-eyed theories but perhaps the conspiracy theorists straining for a glimpse of the real Christopher Marlowe should take a closer look at Romeo and Juliet and in particular the character of Mercutio – one of Shakespeare’s most idiosyncratically drawn characters – a standalone curiosity who defies easy categorisation.

As his name suggests, Mercutio is mercurial, the very personification of Mercury, unstable quicksilver flickering in and out a bewildering array of manic modes: an irreverent contrarian a merciless mocker of pomposity; an infuriating troublemaker; quarrelsome in drink; a brilliant wit; an exhibitionist who demands to take centre stage but also a fiercely loyal defender of his friends.

Mercutio is a collection of maddening and endearing quirks – almost as if Shakespeare is recreating a character that many members of the audience would recognise and remember with affection.

Mercutio’s mortal wound is an innocent-seeming scratch accidentally sustained in a brawl. Assisted offstage to die, Mercutio’s death is traumatising but profoundly moving, almost as if Shakespeare is giving London’s theatrical community the chance to make a fond farewell to their flawed but inspirational friend.

Immortalising Marlowe as Mercutio in tribute might be the most subversive thing that Shakespeare ever did but the clue is in the name: Marlowe had several nicknames but he always insisted his friends call him Mercury.