Murray Moss's Next Act

"If you're on the stage with a spotlight on you, you're Hamlet," says Murray Moss, partly to himself, partly to the group of us standing on a sidewalk in Providence, Rhode Island, waiting for an Uber. "Enjoy it! It doesn't happen that often." In about an hour, on the stage that awaits in Rhode Island School of Design (RISD)'s Metcalf Auditorium, Moss will deliver the second of a pair of fall semester lectures. Each talk is followed by a graduate workshop at the RISD Museum and lays the groundwork for the 13-week Torpedo Lab Moss will lead this coming spring.

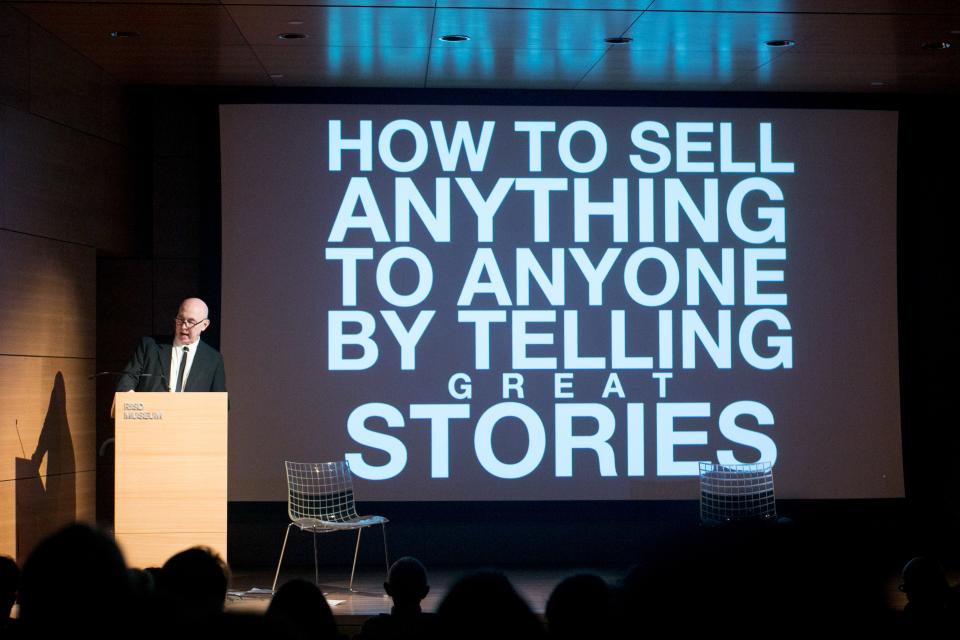

For all of his proclaimed nerves, one thing is clear when the lecture starts: Moss is taking his own advice. He moves, as if on cue, from podium to chair and back again. He reads from a stack of papers, casting finished pages dramatically on the floor. He leaves room for long pauses, to emphasize what he's just said or to give the audience a moment to laugh at a PowerPoint slide of dancing nuns. It's theater.

It shouldn't surprise us. For Moss—the namesake of the now-defunct SoHo design shop–slash–gallery—that's where it all started. Moss was an actor in his early 20s when he met his longtime life and business partner, Franklin Getchell, at a Christmas party given by a mutual friend. They'd meet again only a few weeks later, both newly hired by an American acting company called Shakespeare & Company, which assembled in Stratford, England. Some 20 years later, he'd open MOSS, his very own theater, of sorts, in which he created narratives with a revolving cast of inanimate actors: objects of industrial design, shown museum-style, often behind glass. In one of the special exhibitions, a long line of vintage Sèvres porcelain busts sat on tables designed by Ann Demeulemeester, below shimmering Baccarat chandeliers. In another, hooked rugs from the Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland hung above iconic Italian 'P40' Rationalist chairs by Osvaldo Borsani. In yet another, Studio Job's totems of cast-bronze 19th-century kitchen wares were monumentalized on slick wooden pedestals. As Getchell, who joined Moss in the business about five years in, writes in Please Do Not Touch, the book the pair co-authored and published with Rizzoli this year, "Neither of us ever regretted for a moment the decision to leave the stage. Because we didn’t. It came with us and informed the entire rest of our lives." Thanks to their studied approach, calculated set dressings, and the mandate—Please Do Not Touch—plastered across the walls, design objects were elevated to fine art.

MOSS closed in 2012, the year I moved to New York. I missed the show. But as a writer with a penchant for the less-practical side of decoration, I'm constantly experiencing the aftermath in that ever-tightening space between art and design. As the number of design galleries increases, as Ettore Sottsass gets a show at the Met, as R & Company and Carpenters Workshop Gallery exhibit tables and chairs at the Armory Show, it seems fitting that Moss is back for Act Two, this time as a mouthpiece for the kind of radical design thinking he pioneered with a new target audience: design students.

"What I like about the design school situation is it’s a safe house for an adult to go back to the beginning. You take a vacation from yourself and what you think your beliefs are," Moss tells me in the soaring, colonnaded lobby of Providence's Omni Hotel.

Moss didn't go to design school. In fact, his own design education was rather DIY. At 40 years old, after careers in acting and fashion, he became fascinated with Italian product design. With magazines as his textbooks, he created two instructional file boxes: one for manufacturers and one for designers, cross-referencing them until a core group of designers working with a certain set of producers emerged. For about four years he made index cards that began to profile the key players of the moment, setting the groundwork for his design knowledge. Due to the Italian focus of his homeschooling, in the early days at MOSS there was a large contingent of graduates of the Polytechnic University of Milan, a school that boasts such alumni as Gio Ponti, Achille Castiglioni, and Aldo Rossi.

"There was a more conceptual approach to design," he explains of the Polytechnic University. He later found many of the same qualities in the Netherlands' Design Academy Eindhoven, which produced the likes of Hella Jongerius, Maarten Baas and Studio Job. "The realization of a workable, practical, useable, blah blah blah, functional object was not always someone’s objective. If that is your assignment, then it’s valid to use that as criteria. But it doesn’t have to be. I don’t think that’s entirely understood here."

It's this type of thinking that made MOSS different than, say, the MoMA Design Store, and it's something that Moss himself wants to drive home with his students. As he writes in the book, "Do I really care about how well fruit bowls aerate fruit? Do I really care about how many ounces a drinking glass holds or how ergonomic a letter opener is? NO! I care that a drinking glass be fragile and expensive and the thinnest possible barrier between one’s lips and the liquid, because using such a valuable and yet fragile object will require that we alter our behavior and become more graceful, less brutish. I care about such a glass because if it breaks, it is a tolerable loss and yet still elicits in us that ever-more-rare bittersweet feeling of vulnerability. A beautiful, thin-walled, mouth-blown—and therefore unique and irreplaceable—shimmering glass gives me something to cherish."

When function takes the back seat, Moss suggests, something else emerges: narrative. He made this the subject of his first RISD lecture, delivered in October, and illustrated with a series of, well, narratives: the story of his failed L.A. outpost, the story of Constantin Boym's Ultimate Art Furniture (tables and chairs made out of painted canvases), the story of his mother's beloved Shalimar perfume bottle.

"I want them to know the subject is not only about getting to the solution the quickest way possible," he explains. "It doesn’t have to be so practical. Maybe the chair’s not comfortable but the chair is... stimulating. It can feed us in other ways."

After the lecture, Moss tasked the group of 15 grad students with photographing objects from the RISD Museum collection and placing them in new conversation with one another. "He asked us to think about what you can add to a collection or take away from it that would change the meaning of what you’re seeing," explains ceramics student Sarah O'Brien. "You realize the power that other objects have on your perception of a separate object. You don’t control the objects themselves, but you can control how they’re put together or separated from other things, and how that’s read by the viewer."

For Emily Guez, a graphic design student who had previously relied heavily on text to convey narrative, there was another kind of epiphany: "You can tell the story without asking people to read. You can put images or objects together in a way that evokes an idea."

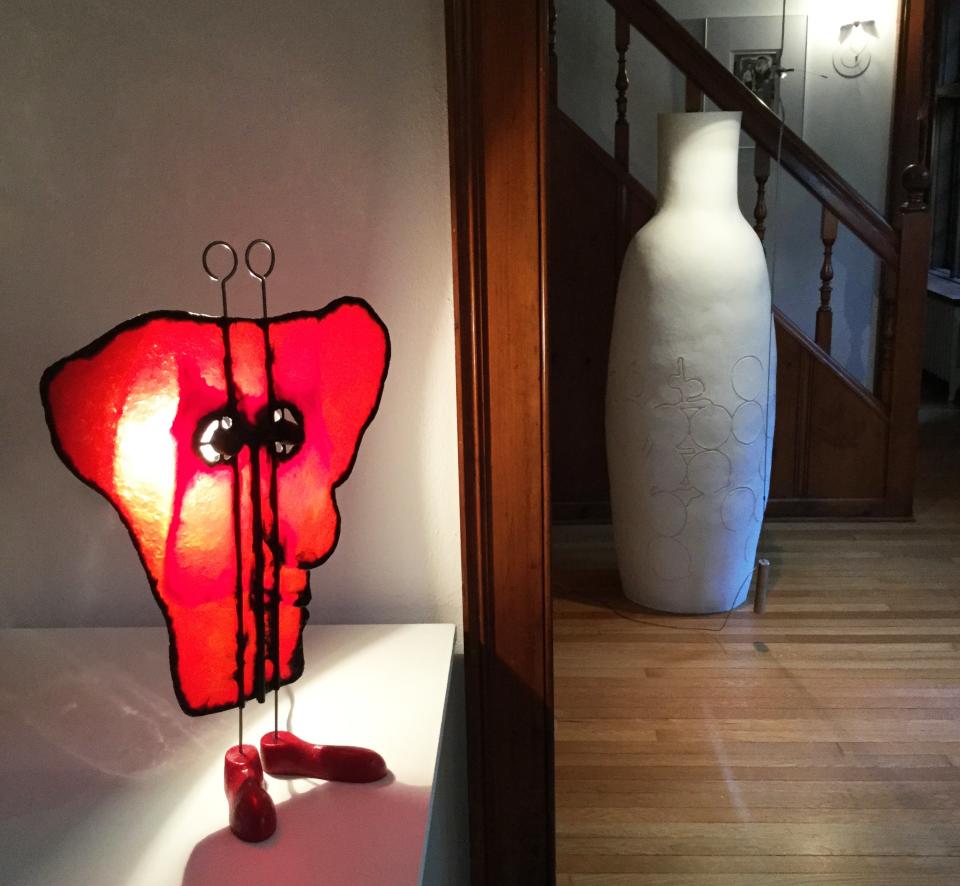

For the second lecture, Moss talked about the idea of interdisciplinary design, a concept he suggests should actually be traded for the more radical "anti-disciplinary design," coined by Joi Ito, director of the MIT Media Lab and defined as "someone or something that doesn't fit within traditional academic discipline" or "people who play in the space between disciplines." Afterward, grad students would engage in a lively dialogue on the subjects of the lecture. In the spring, he'll invite the graduates to Torpedo House, his and Getchell’s residence and conference center in Hamden, Connecticut, where they'll see and talk about Moss's personal juxtapositions on display throughout the space.

It's not only students Moss has rubbed off on. Simply look at the success of Design Miami—at R & Company an army of six girl sculptures-slash-lamps by Katie Stout sold for $55,000 a piece in the first hour; at Jason Jacques a Beth Cavener ceramic work went for a whopping $250,000—or ask around the downtown design scene, and Moss's influence is on display.

"I can’t really count the ways he's influenced my work," says Melanie Courbet, who recently invited Moss to co-curate a show of Lobmeyr crystal at her Chelsea design gallery. "He is a great model and a source of inspiration for his uncompromising vision, his elegant way of concealing the hard work and the high level of risks and commitment that it takes to make it all seamless and playful."

But even as the subjects of design and art become more enmeshed, it's surprising how siloed our language remains.

"I’ve always been interested in—I’ll just say it—decor," Moss says, acknowledging the scandalousness of the term.

"I’m going to change that," he declares, musing on how he might further influence higher education around the matter. Recalling a recent lecture he attended at Yale, he says: "They’re pretending people build these $2 billion buildings and there are no things inside of them. That’s a lie! I was thinking, I would love to start a school there with a very politically incorrect name. I’d call it interior decoration, which makes people just want to die."

More from AD PRO: Has Instagram Made Design Shows Better?

Sign up for the AD PRO newsletter for all the design news you need to know