The Museum Lockdown Culture

What’s happening to the museum world? I was a museum director for ten years and a curator for years before that. Sometimes I shake my head in bewilderment and chagrin.

The biggest museum scandal in my time, bigger than the Gardner theft (13 works of art stolen, and to this day never recovered, from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum), is the museum lockout culture that developed during the COVID-19 hysteria. I’ve written about this many times, but it bears repeating and embellishment since there’s so much fallout.

There’s the strangest new dynamic in museums these days. I think it’s infecting the entire not-for-profit world, too. They’re absorbing the ethos of public-school teachers’ unions.

I like teachers. I taught for years. In my hometown, little Arlington in Vermont, our teachers are fantastic. They didn’t want to abandon their students, most poor and special-needs kids, in March. The COVID hysteria, though, hung these children out to dry, and our teachers did their best. They’re teaching in person now. They wanted to return to the classroom. They’re not selfish.

Anyone who reads the news or has kids in public schools sees the contortions, the machinations, that teachers’ unions have used to keep schools shut. Online teaching is a much-reduced work burden, and you do it in your slippers. Standards are relaxed. The worst students tend to be truants.

Overall, though, I’m seeing in museums, starting with the lockdown, the same lethargy, comfort seeking, internal focus, and intellectual flabbiness that exist in big chunks of the unionized public-employee sphere. It’s a strange new ethos of entitlement, an assumption that the public’s interests pale compared to the staff’s. The two worlds seem to be merging. And there’s another similarity. The only thing beyond their convenience that seems to animate them, the one thing out in the real world that appeals, is left-wing fanboy politics.

I have an old-fashioned notion that core civic enterprises like museums should never close unless there’s a natural disaster on the order of the blizzard of 1888, the Black Death, the eruption of Vesuvius in a.d. 79, or the Great Flood. Museums are keepers of heritage, but they’re also icons of a living, functioning civic order, or, to use a broad term, civilization. They’re meant for the public’s edification. When I worked in a museum, I felt that I served the public.

Let’s face it. Keeping a museum closed for six months for the coronavirus — the mortality rate is about the size of a bad flu season — is negligence. I don’t care whether the directors and other senior staff stay in bed all day, go surfing, garden, or watch The Queen on Netflix. That’s between them and their trustees. I do care about the public’s right to go see art in their galleries. I take seriously the duties of not-for-profits to serve. That’s why museums don’t pay taxes, and the philanthropy that runs them is tax-free.

The nationwide lockdown was the worst case of government malfeasance since the Vietnam War. An ignorant, opportunistic press and public-health quacks cowed politicians and the entire country. Gloom-and-doom pimps goosed death numbers to keep the crisis going and the fear keen. Aside from Dr. Birx’s taste in Hermès scarves, I’ve seen nothing from our public-health bureaucracy that favorably impresses.

That said, the government made the decision to shut the economy, and this, in my opinion, justified museums’ decisions to keep full staffs on the payroll while closing their doors, but only for a period of weeks, not six months. The China-virus catastrophe has drawn the curtain on what museum leaders really believe — their comfort and convenience come first, the public’s interests, well, who cares?

All roads stop at the trustees’ doorsteps. Trustees of museums are usually rich, often corporate types, which means they’re working at home. If a trustee’s office is in New York, it’s likely he or she hasn’t seen it for months. Well, trustees assume, doesn’t everyone work from home these days? The answer is “no,” and not everyone noshes on caviar and champagne before dinner. A high-flying money-pusher has no obligation to the public, laws against swindling notwithstanding, but a museum exists to serve the public, and that means keeping the doors open. That high-flying money-pusher trustee has a fiduciary responsibility to see to it that this happens.

Barring the public — keeping the doors locked — is one scandal. The health protocols are simple: hand-sanitizing stations, masks, and plexiglass shields for staff. Thousands of supermarkets and essential factories did what they needed to do, and fast. I’d suggest that museum leaders bring a customer-satisfaction team from Kroger, Ralph’s, Stop & Shop, or Piggly Wiggly to get a refresher course on service.

Museum leaders could have moved as quickly but wouldn’t, and that’s another scandal. As soon as President Trump said he wanted to see the economy reopened by the end of April, many decided they were going to string the lockdown out for as long as they could. “Trump wants it. . . . We’re not doing it.”

This is the message I got from many of my museum-director friends. The lockdowns started as government mandates. Then they became political stunts. Soon, museum brass turned into lockdown-leisure addicts. It’s nice, they discovered, to Zoom away the workday.

I’ve noticed one more bit of fallout this week. College and university museums are staying closed to the public while almost all civic museums finally, grudgingly, are opening. There are hundreds of these museums. They serve countless communities beyond students and faculties. All are normally open to the public and usually free. For many colleges and universities, sitting on hundreds of acres of prime real estate exempt from property taxes, their museums are the only on-campus goodies the locals can enjoy.

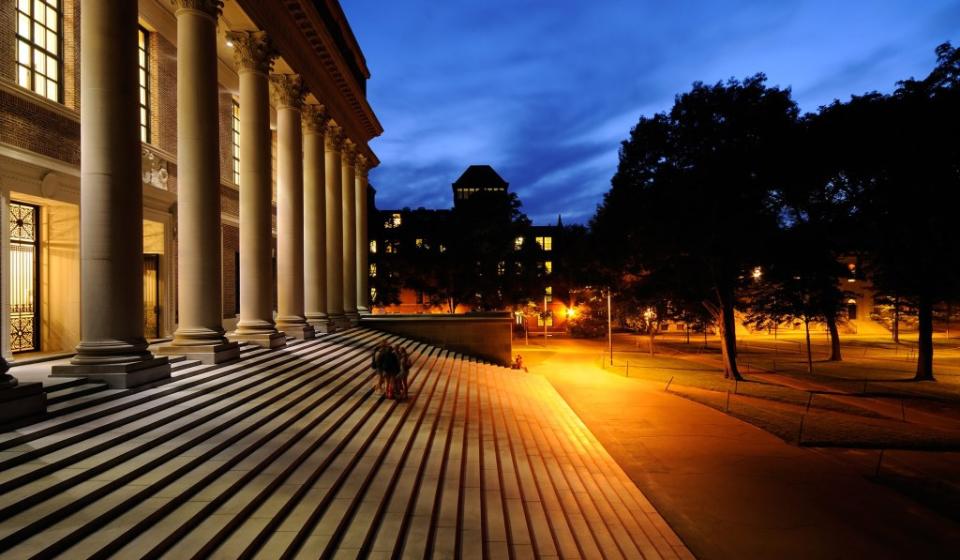

I did a limited, though, I think, authoritative survey of New England college and university museums. The Fogg at Harvard isn’t opening anytime soon, to anyone. Wussy Harvard, for the first time since 1636 — that’s 384 years — isn’t doing any teaching in Cambridge. Harvard managed to teach students during the Pequot War and King Philip’s War, both unfolding around the corner from Cambridge. Hey, Harvard, isn’t getting scalped more problematic, more worrisome, than COVID?

Harvard taught during the witchcraft hysteria of the 1690s, the American Revolution, the Civil War, the Second World War, and killer epidemics of smallpox, measles, diphtheria, and the Spanish flu. Each of these epidemics struck the young, but it took COVID-19, of all things — a disease hitting nursing homes and sufferers of dementia, diabetes, and obesity — to scatter Harvard’s bloated plutocracy to the hills.

Fighting Crimson has turned Fleeing, Frightened, Hiding Crimson. I don’t think Harvard cares that much about its undergraduates — it’s all about the faculty’s research and, to a lesser extent, its graduate students. And Harvard certainly couldn’t care less about the people living in Cambridge. Still, the Fogg is one of America’s great museums. It’s a shame it’s closed. I hope donors take note and steer their gifts to Yale, which is open for teaching and whose venerable art gallery is open to the public.

The Rhode Island Institute of Design museum is open only to RISD ID-holders. The Hood, the art museum at Dartmouth, is closed to the public, as is the very good Smith College Museum of Art. This is wrong. These three museums, like Yale, are not only the museum for students and faculty at their schools. They’re the local civic museum. The Yale University Art Gallery has always had a high public profile. I grew up near New Haven, so I know this and benefited from this.

The RISD museum is the civic museum for people in Providence. The Hood serves the Upper Valley, the hundred or so towns along the Connecticut River and inland in western New Hampshire and eastern Vermont. The Smith museum serves Northampton and dozens of towns surrounding it. Their public profile is part of the negotiated tranquility between Town and Gown. The schools, in keeping their museums closed, have jettisoned the deal, flipping the public an Ivory Tower bird along the way.

I’m not troubled by the Williams College Museum of Art’s decision to serve only students for the time being. It’s a modest place and mostly serves Williams students under any circumstances. The locals go to the Clark Art Institute or Mass MoCA. I do find it strange that students wanting access to the museum have to give the place 48 hours’ notice.

If I were paying $70,000 a year for my kid to go there, I’d expect snap-to, on-demand access. You can’t even pop into the museum! You need to have a class assignment. Why does the staff need 48 hours’ notice? “Holy moly, a student’s coming. . . . We need 48 hours to get into our germ-proof bubble.” Is that what they’re thinking? It’s another example of museums forgetting who they serve. It’s not about the staff. And, by the way, there’s no COVID-19 in rural northwestern Massachusetts.

There are many other college and university museums outside New England that once welcomed the public but are now locking their doors. The Princeton museum is one of them. As is the case with Harvard, this is disgraceful. The University of Michigan museum is the only art museum in Ann Arbor. It, too, is locking the public out.

I wonder whether these places will ever open to the public again. Even if they do, someday, condescend to welcome the riffraff and hoi polloi, will they do it meanly, offering bare-bones programs aimed at the community and visitors who aren’t students?

What I’ve seen from the museum community generally over the past six months is a new, disturbing interiority. Public service seems to have gone out the window, down the toilet, don’t let the door hit you in the patootie. Even in the cascade of open letters that museum staffs are dropping — the ones accusing their masters of racism and misogyny — the anger is focused on inner machinations of museums and have nothing to do with the public’s right to enjoy art.

I’ll write more about these open letters since they make for yet another scandal. All of them, more or less, raise the same issues. Who gets this or that job or promotion, who feels slighted or shunned, who doesn’t get enough mentoring, which means babysitting, whose opinion isn’t valued, and, the unnerving, narcissistic lament, “You don’t listen to me.” These questions, and the demands that go with them, have nothing to do with art, have nothing to do with serving the public, and are of no interest to the public.

I’m happy, and relieved, that the Addison Gallery, the museum I directed for ten years, is opening to Phillips Academy students and public alike. The Addison is the art museum for a prestigious, demanding high school, but it’s also the civic museum for the Merrimack Valley in Massachusetts. The Addison has one of the grandest collections of American art in the world. The Met and the Boston Museum of Fine Art are encyclopedic museums, but the Addison’s American art is as good as theirs.

I don’t even mind that the Addison was closed. I hear it did some good virtual teaching. It needed a break and time to recover. After I left, its masters hired a disaster to replace me. She left just before the lockdown after a dismal, lumpen five years as director. She didn’t like the public. True, I brought an unusual mix to the place — piquant, energetic, visitor-focused, and still very egg-headed. And, alas, true again, a director can only, at best, leave things in good shape. A successor builds on the foundation or breaks it.

She’s gone to the Detroit Institute of Art, to a job that involves budget and registrarial work. I can’t say she’s not capable for this. The Addison is doing a search, and I hope they find a director who, at least, wants to serve people. Nothing bothers me more than a museum director who looks at someone and makes a snap judgment — “VIP” or “this person doesn’t count” — and then proceeds to blow off those-found-lacking. This public-be-damned attitude is, alas, becoming a pandemic in itself.

I’m skeptical of the breathless, earnest cattle drive toward equity, inclusion, diversity, and accessibility. Insofar as this involves staff composition, it’s an expenditure of time, energy, and money that’s really not benefiting the public except in a remote or abstract way. Given all the lockdown love, I’d call the talk about accessibility and inclusion fake.

You don’t get to accessibility and inclusion by keeping everyone out.

The open staff letters loudly accusing museum management of racism don’t seem to make museums more attractive to black or Hispanic audiences. Are these good people more likely to visit a museum disparaged by its own employees as being run by white supremacists? I think not, and this is yet another scandal I’ll write about in a week or so. Why are people who are dissing their museums in screeching headlines still employed?