Museums may still be shut, but commercial art galleries are opening – here's what to see

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

One pitfall of being a critic is getting jaded. Another Picasso blockbuster? Yawn. No chance, though, of that over the past year, with exhibitions rarer than hens’ teeth. It’s been so long since I reviewed an actual show, rather than a bunch of jpegs dressed up as an “online viewing room”, that, now, you could offer me anything – even a banana duct-taped to the wall (which, as it happens, the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan presented recently) – and I’d give it five stars.

So, last week, as the nation’s commercial galleries prepared to reopen alongside gyms, hairdressers, zoos, and nail salons (how grubby to be bracketed with business and not lofty museums, which, unfathomably, must wait another 35 days before welcoming back the public), I decided to visit as many exhibitions as I could. Fourteen of them, in fact, providing 10 hours of sweet relief, experiencing art as God intended – not flattened and pixelated on a smartphone’s screen, but close-up, at first hand. So much gets lost in digital translation: the subtle chemistry of interacting colours, the claggy textures of oil paint, the coarseness or delicacy of a line, paper’s idiosyncratic bumps and rumples. Despite the hegemony of Instagram, art exists in three dimensions.

A lot is worth catching, so long as you’re willing to be reminded of recent hardships. Curiously, much is German: etchings of wracked and wrinkled hands, evoking a sense (touch) which everyone has missed, by Georg Baselitz at Cristea Roberts Gallery (until May 15); Sabine Moritz’s abstract maelstroms at Pilar Corrias (until April 17), dramatizing the pandemic’s non-stop, blaring news cycle; Markus Lüpertz’s grand, sombre paintings of statuesque figures within autumnal landscapes, at Michael Werner Gallery (until May 15), which have the mossy, mildewed air of old ruins. Who hasn’t, recently, felt a touch of “weltschmerz”?

At Gagosian, Rachel Whiteread, whose sculptures are often explicitly memorial, offers her response to the crisis (until June 6). She’s famous for casting the interiors of things: hot-water bottles, cardboard boxes, even a Victorian townhouse. Here, though, two rickety structures, assembled last year, provide the centrepiece. Seemingly cobbled together from debris and scraps – splintering wooden planks, uprooted trees, wire netting, crumpled corrugated iron, all painted a ghostly matte white – they appear to be exploding, and have a theatrical presence: they’d make excellent scenery for a production of Beckett. Two shacks blasted by… a tornado? Some malevolent cosmic force? It’s hard not to read them as monuments to the fragility of human life. When it comes to who should design a national Covid memorial, Whiteread will be the frontrunner.

The show’s title, Internal Objects, summons up lockdown, which forced us inwards, stuck at home, reliant on psychological reserves. Claustrophobic domesticity inspired British painter Dexter Dalwood to stage a fascinating display, at Simon Lee Gallery (until May 8), of little-seen preparatory collages, reminiscent of work by Richard Hamilton, for uncanny, figureless paintings imagining interiors inhabited by famous people. Ever wondered what Bill Gates’s bedroom looks like? Dalwood takes us through the keyhole.

Interiority, in a different sense, informs a new series of vaguely Rothko-like abstract paintings by British artist Idris Khan, upstairs at Victoria Miro (until May 15). Against a deep blue ground, Khan repeatedly stamps words and passages written during lockdown to produce dark floating rectangles of verbiage so dense they are illegible. Here we are, imprisoned in our minds at 3am. By contrast, Khan’s foray into colour downstairs, a suite of 28 pictures riffing on Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, with daffodil yellows and bluebell hues, feels glib.

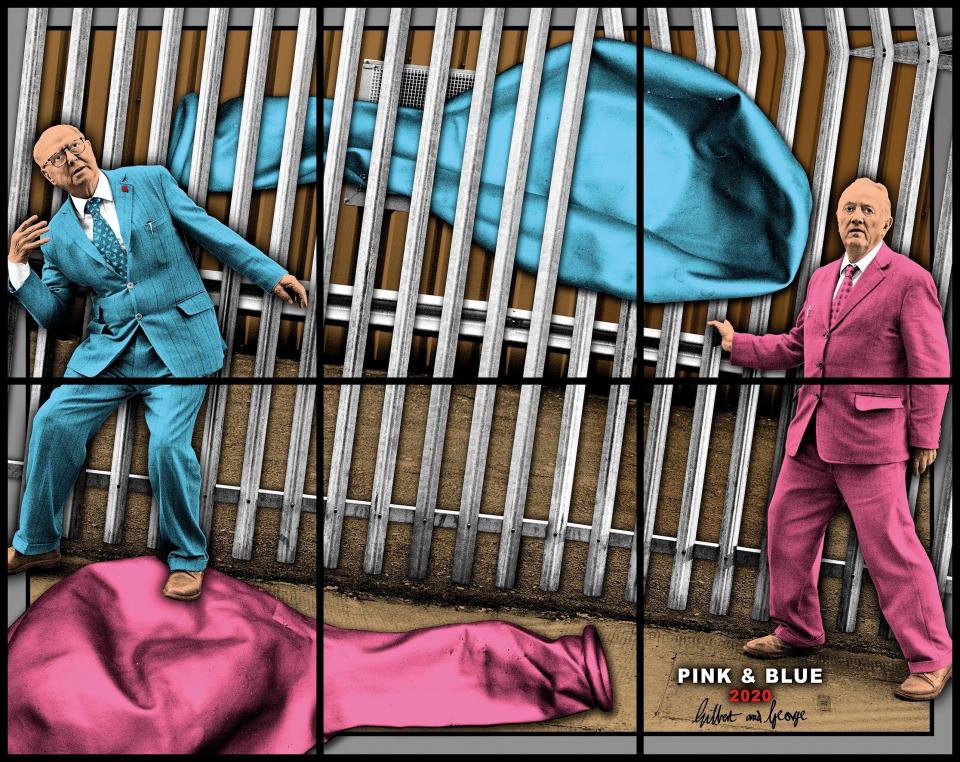

At White Cube Mason’s Yard, Gilbert and George pound the streets of Spitalfields (until May 8), stomping over bin bags, hanging out with the homeless, slumping across bus shelters. Apparently, they came up with the title for their “New Normal Pictures” before Covid struck – yet, these enormous compositions, like panels of hallucinatory stained glass, feel apocalyptically of the moment. At the same time, they’re full of wit. Hamming it up, even posing, surreally, with gigantic, flaccid balloons between their legs, the pair, now both in their late seventies, are clearly having a blast.

Likewise, the Swiss-born artist Ugo Rondinone. Four raucous multipart paintings at Sadie Coles HQ (until May 14) – each consisting of several bright, irregularly shaped canvases, like squashed boulders, stacked to form an impossible, precarious cairn – are unashamedly joyful. Just the ticket, in fact, as we move from wintry lockdown into spring. Around the corner, on Kingly Street, Rondinone is also showing 15 sculptures of horses cast in various shades of blue and turquoise glass. A horizontal join bisecting each animal conjures a horizon line between sea and sky. That may sound jolly, a Magrittean daydream of summer holidays. Yet, Rondinone’s meek, static creatures have doleful expressions. This herd of translucent Eeyores is lost in thought. Interiority, again.

Even art made long ago can resonate afresh during a pandemic. Inside a Mayfair mansion, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac is mounting a classy show (until July 31) of two series of metal paintings from 1991 by the American artist Robert Rauschenberg. Both are monochrome, and feature diverse, complex photographic imagery silkscreened onto aluminium: brushed, in the case of the “Night Shades”; mirrored, with the “Phantoms”. Because the latter’s surfaces are reflective, their imagery is harder to make out – though this only intensifies their spine-chilling, spectral effect.

Overlaid with glowering, gestural swirls of black, like irascible storm clouds, the “Night Shades” are more straightforwardly sombre. One, featuring the World Trade Center, feels prophetic: if you were told it was a 9/11 picture, and didn’t know otherwise, you’d go with it. In another, a horned skeleton brandishing a weapon looms above a newlywed couple. Three decades on, death still walks among us, just as brazen.