Museums robbed hundreds of Native graves. Now they're trying to repair the damage.

Nineteen leather medicine pouches, hand-stitched by members of the Oneida Indian Nation and arrayed on a purple woolen blanket bearing the emblem of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, were the only visible symbol Wednesday of a small step toward addressing a grievous historical wrong.

They represented the 19 Oneidas whose bodies were dug up in the 20th century and taken to the Rochester Museum and Science Center. At a repatriation ceremony, museum officials formally transferred the remains and associated funerary items back to the Oneidas for reburial.

The Oneidas traditionally bring the medicine pouches with them on long journeys, said the nation's representative, Ray Halbritter. In this case, the journey will take the Oneida ancestors -- five men, three women and two girls, plus others who could not be identified, some from the 19th century and some thousands of years old -- from the shelves of RMSC to their final resting place on Oneida land.

"Ceremonies like these … are an acknowledgment of our ancestors’ status as real people who lived lives – rich lives – and deserved dignity in life and dignity in death," Halbritter said.

The 19 human remains returned to the Oneidas this week represent a small fraction of the bodies that RMSC excavated or purchased, mostly between the 1920s and 1960s. At the peak of its collection, the museum held the remains of around 1,000 human beings on its shelves.

In 1990, Congress passed a landmark law, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, acknowledging museums' past failings and facilitating the repatriation of human remains and funerary objects to their rightful resting places.

Thirty-three years after NAGPRA went into law, though, RMSC still possesses at least 400 human remains, most of them Seneca ancestors. Over the years it has complained about a lack of funding for the enormous task of creating an inventory and notifying Native tribes of what it held.

"This repatriation should have occurred a long time ago," RMSC CEO Hillary Olson said. "The ancestors and their belongings should never have been in the RMSC in the first place."

After decades of opposition and delay, RMSC in the last two years has dedicated the necessary time and money -- more than $100,000 of its own operating funds, Olson said -- to finalizing that inventory and now is working with Haudenosaunee and other tribes and nations to send them home.

A much larger repatriation effort is in the works. Christine Abrams, a Tonawanda Seneca and acting chair for the Haudenosaunee standing committee on burial rules and regulations, said the museum and the two federally recognized Seneca nations are in active talks to return about 400 human remains. The transfer should happen "soon," she said.

"It is incumbent upon institutions with legacies stained by the acquisitions of ancestral remains … to act with great urgency in righting these wrongs," Halbritter said. "Every minute that the remains of our ancestors and our cultural artifacts are not returned continues this shameful legacy of abuse inflicted upon native people."

Scientific rationale led to desecration of Native sites

Some of the human remains at RMSC were donated or sold to it over the years by collectors or amateur archaeologists. In other cases the museum received a call from road crews or others who came upon a grave by accident.

Most, however, were excavated by archaeologists employed by the museum whose goal was to find burial sites and remove the remains and items inside for study.

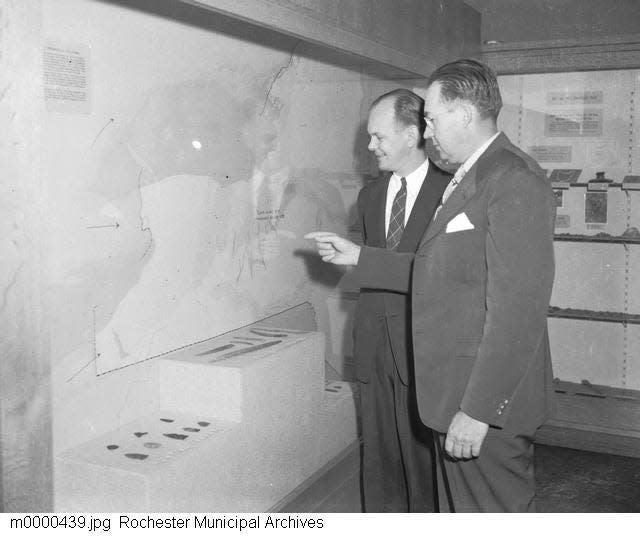

The first prominent RMSC archaeologist was Arthur C. Parker, a Seneca who served as the museum's second director, from 1924 to 1945. The name most associated with mid-century Haudenosaunee archeology, and therefore with grave desecration, is William A. Ritchie, who apprenticed with Parker and then headed RMSC's archeology division in the 1930s and 1940s.

Ritchie led an estimated 100 excavations in his long career, mostly in New York and New England, and wrote textbooks that are still in print today. He left RMSC in 1949 to become the chief archaeologist at the New York State Museum, a post he held for more than 20 years.

Parker and Ritchie decried the collection of human remains for private curiosity cabinets but advocated enthusiastically for excavating burial sites for scientific purposes. They and most archeologists of the time argued that digging up and studying (non-European) human remains was more respectful than leaving them in the ground.

"These human bones ... are more than just curios -- they are the records of people," Ritchie said in 1949. "Furthermore, they are the only records those people left, for they had no written language."

The exploits of Ritchie and other RMSC archaeologists were a regular feature in local newspapers from the 1930s to the 1960s. When possible they were accompanied by up-close photographs of the physical remains themselves.

An article in the Democrat and Chronicle about one of Ritchie's excavations in 1933 begins: "After lying undiscovered for centuries while white men built their civilization along the Genesee River, four Indian skeletons were yesterday taken from the earth two miles out on Chili Road and placed in the Municipal Museum of Arts and Sciences."

In 1956 a story described how RMSC archaeologists dug up the remains of at least 65 people near the northern end of Honeoye Lake. And in July 1964 the Democrat and Chronicle ran a week-long series on the museum's archaeological activities in Haudenosaunee lands, illustrating each installment with a photo of human skulls.

One recent federal notice posted by RMSC illustrates how near to Rochester many of the excavations were. It lists remains that were taken from graves in Chili, Henrietta, Penfield, Riga, Rochester, Rush, Scottsville, Webster and Wheatland, as well as Ellison Park and the Sea Breeze neighborhood in Irondequoit.

More: Senecas buy Canawaugus land along Genesee River

In his remarks Wednesday, Halbritter rejected the purported scientific rationale for pillaging Native gravesites.

"To have our land taken and stolen would have been hardship enough," he said. "With it our culture, our history and even our children were taken, again with a denial of our humanity that (excused) any atrocity against the Native American as long as it served a nebulous greater good that always excluded our own."

Resistance to repatriation

RMSC stopped publicly displaying human remains in 1972 and stopped accepting them into its collections in 1979. But throughout the 1980s, as momentum built toward a federal repatriation directive, the museum resisted.

In 1984 it declined a request to return ceremonial masks to the Onondaga Nation, citing obligations to donors and scholars. And in 1989, one year before NAGPRA became law, two RMSC researchers wrote an essay arguing against "mass reburial of our nation's museum collections" of Native American remains.

"Reburial on a national scale would involve destroying a truly immense quantity of artifacts," Martha Sempkowski and Lorraine Saunders wrote. "How can we conceive of destroying this ... valuable record of the unwritten past without serious consideration of the irretrievable loss of information?"

After NAGPRA became law in 1990, one of its first major deadlines was in 1995 when museums were supposed to complete an inventory of human remains and associated funerary items in their possession. RMSC missed that deadline, saying it needed federal resources to complete the massive task.

Some repatriations followed. But it was not until the last few years that the museum dedicated its own resources to finishing at least an initial survey.

"We have not been timely in moving forward with our obligations," Olson said Wednesday.

'A long time coming'

Thirty-three years after NAGPRA was enacted, there are some signs of momentum for repatriation among museums as well as growing pressure from tribes.

In November 2022, Colgate University returned 1,500 funerary items to the Oneidas. This March, Cornell University returned the remains of three Oneida ancestors.

"There's so much out there, it takes some prodding from us," said Abrams, chair of the committee that works on all Haudenosaunee repatriation efforts. "And sometimes we can't even keep up with all the notices. It takes both sides to work on it so it takes a while to get together. ... But it's been a long time coming."

Much work remains to be done. RMSC says its first goal is to repatriate remains and funerary objects from New York state, the bulk of its collection. But NAGPRA records show it also holds human remains and funerary objects from across the country, and many whose origin it does not know.

More broadly, the museum is looking to build a respectful relationship with Native people and to create programming that reflects their culture today, not just in history. Next year, for instance, RMSC will present a new exhibit called Haudenosaunee Continuity, presenting contemporary Haudenosaunee artwork. It was developed together with Seneca cultural educator Jamie Jacobs.

The nations of the Haudenosaunee, meanwhile, are among the most studied in North America, meaning that items from their burial sites are widely dispersed. For example, NAGPRA records show that 271 institutions across the country hold Seneca remains or funerary objects, including 29 in New York.

For Native leaders, however, the goal is not to tally stolen objects but rather to honor their ancestors.

"We feel it creates unrest among ourselves when our ancestors are on shelves and in boxes for so many years, nothing being done for them," Abrams said. "We’re just doing the best we can to lay them back in Mother Earth and let them continue on the journey that was interrupted."

Justin Murphy is a veteran reporter at the Democrat and Chronicle and author of "Your Children Are Very Greatly in Danger: School Segregation in Rochester, New York." Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/CitizenMurphy or contact him at jmurphy7@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: RMSC returns Oneida remains, apologizes for desecrating tribal graves