This music and the values that go along with it: Trio Imagination coming to the Big Ears Festival

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Big Ears Festival encompasses more branches of the musical family tree than any other arts congress on Earth. From pop to punk, classical to cumbia, East African to Estonian. From bang on a can to reach for the stars.

But no music at Big Ears is more important than the music whose name is the same in every language, the music without which this world would be less hospitable than Mars. It’s the music of Ella, Duke, Bird, and Monk, the four-letter synonym for real, free, and true.

Jazz.

“Jazz is freedom. Just think about that.” _ Thelonious Monk

In the most recent edition of Jazz Times, UCLA professor of American History, Robin Kelley, has a piece called “Finding a Voice For Black Jazz,” excerpted from a new book edited by Willard Jenkins, "Ain’t But A Few Of Us."

Kelley observes that “Historically, few jazz musicians fall into the category of the solitary tortured individual artist but instead come from a community that has nurtured, taught, and profoundly shaped the musician’s path. It allows us to see how this music and the values that go along with it are learned and passed down ... and how this music is consumed and engaged.” It also makes the point that originality is a communal necessity.

But then, having raised the question of how values are passed from generation to generation, Kelley zeroes in on a weak link: “I don’t think there is a whole lot of interest in jazz on the part of young black writers and scholars. Our collective musical literacy is quite low.”

Then he goes to the heart of the weakness. “I think all of us need to take responsibility for our lack of musical literacy. Arts education has deteriorated. It has become merely a means of self-expression and narcissism rather than a body of knowledge or a mode of interpretation. So my students don’t know how to read a poem. Even those who play an instrument do so in such a mechanical way that they have no philosophy of music.”

Illinois just reported that the state has 30 schools where not a single student can read at grade level. And there are 53 schools where not a single kid is functioning at grade level in math. How are you going to explain the 12 bar blues to a kid who can’t count to 10?

The irony is that Kelley’s observation comes a year after the writer Hanif Abdurraqib’s Big Ears 2022 appearance displayed a clarifying musical literacy that has adapted to the new modes of idea trading. The problem, though, is this: as Abdurraqib’s MacArthur “genius” grant attests, his intellect is rare. His insights are unique and probably unteachable. They can be appreciated, savored, and enjoyed, but taught? Probably not.

If Hanif Abdurraqib hosted a weekly 90-minute live television broadcast on PBS for eight to 10 years, his brilliance might have its due impact on American musical literacy. But we don’t do TV anymore. If he was Christian McBride’s co-host on “Jazz Night in America,” his brilliance might have its due impact. But a MacArthur grant just gives you money and bragging rights. It doesn’t give you due impact.

“There’s no excuse for young people not knowing who the heroes and heroines are, or were.” _ Nina Simone

Kelley’s thoughts reflect a conundrum that may be paralyzing to jazz in the near future. Jazz has repeatedly gone through cycles of self-doubt and creativity recessions, rescued by the emergence of young bloods who need no coaching to pick up the pieces. They just do it.

But this raises other questions.

Are there 12-year-old kids right now listening to Antonio Sanchez on the radio late at night when they oughta be asleep? Or Jason Moran? Esperanza Spalding? Makaya McCraven? Do kids collect John Zorn records? Do they know who Reggie Workman is? Do kids know how much Charles Mingus worried about them? How much he cared about their musical education?

Nope. They’re too busy playing Minecraft. And too many kids don’t have fathers in their lives. Trust me, it’s all related.

“It isn’t where you come from. It’s where you’re going that counts.” _ Ella Fitzgerald

My dad was an audiophile. He loved the Big Bands. He loved Duke Ellington, Sarah Vaughan, Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, Frank Sinatra, Buddy Rich, Louis Armstrong. He loved great music. It took the edge off of going to K-25 every morning. And he loved to dance to great music with my mom. How else do you have seven kids? I mean, really. He put a theater-grade mono speaker in the wall of our C-house on Maple Lane that probably registered on seismographs in Golden, Colorado.

“I start in the middle of a sentence and move both directions at once.” _ John Coltrane

In 1961, when I was 9, jazz bassist Reggie Workman performed on John Coltrane’s “Live at the Village Vanguard,” and on Eric Dolphy’s “Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise,” two universally recognized classics in recorded jazz. He was 24. Three days ago, I called Workman to talk about how the music and its values are being passed down in this decade.

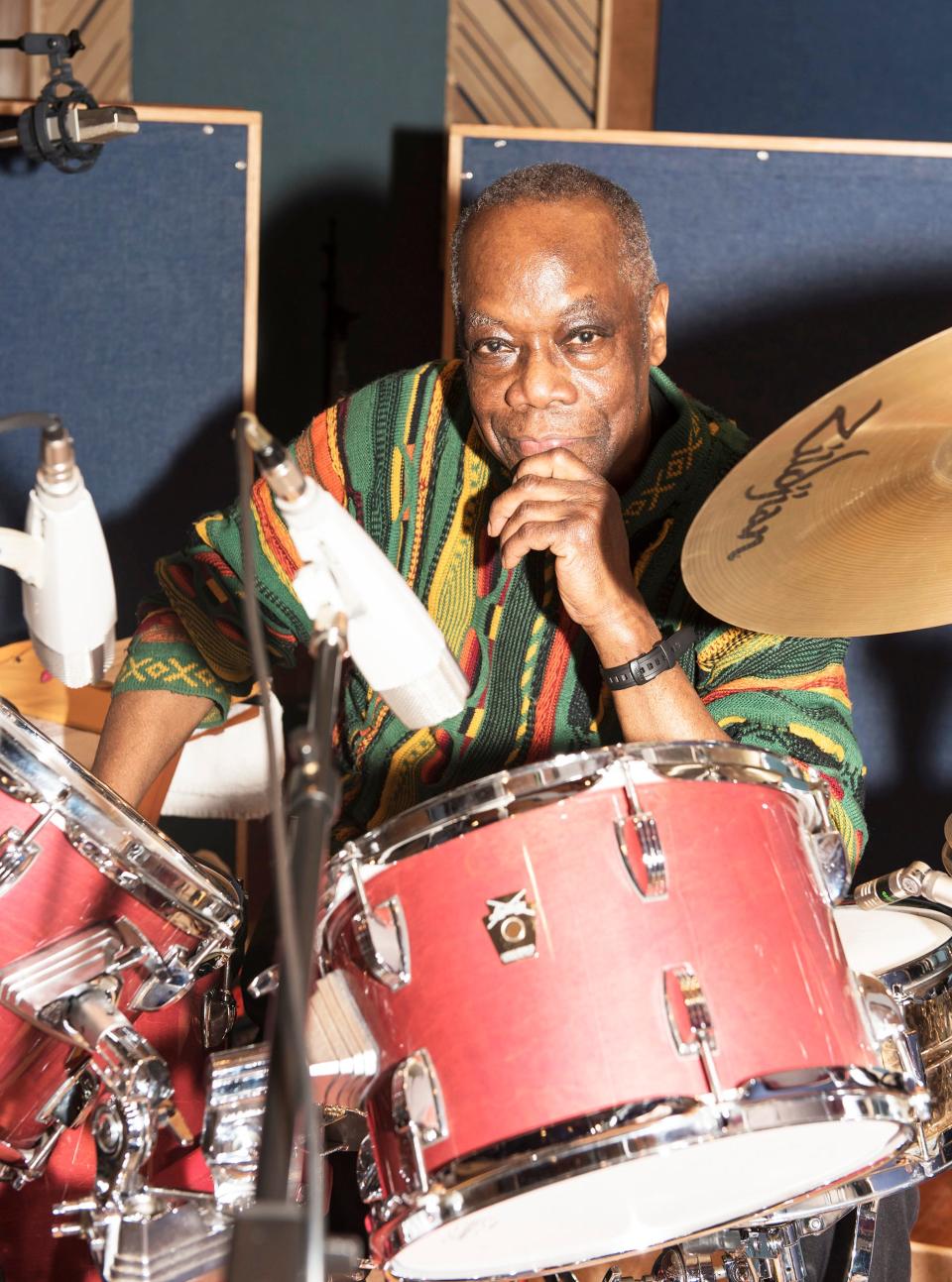

I’m 70 now. Reggie is 85, and his name is on more than 300 jazz albums. In a little over a month, he’s going to light up the Big Ears Festival with David Virelles and Andrew Cyrille. I’ve never spoken to a more vibrant, focused, energetic, thoughtful, reflective, wise, or enjoyable man in my life.

Workman, Virelles and Cyrille are a jazz unit called Trio Imagination. The band was originally put together by Oliver Lake of the World Saxophone Quartet, but when Lake retired in 2020, the Trio was re-imagined with the young Cuban piano genius Virelles.

Workman was named in 2019 as a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts. So I started our conversation by telling him that one of the most recent class of NEA Jazz Masters was a dear friend of mine: Sue Mingus, widow of the great bassist Charles Mingus. (She passed away five months ago at age 92.) I told Reggie that Sue invited me and my theater collaborators to participate in a tribute to Mingus at Carnegie Hall 40 years ago, and that I took a bow on the edge of that historic stage standing between Dannie Richmond and Horace Parlan. That’s all it took for me and Workman to go deep.

“Well, if you’re throwing around names like that,” he said.

Where much is given, much is required. And jazz has given me more than I can put into words, in terms of how I understand this country and its culture. You find the heart and soul of America on the sidewalks of Treme and at Tipitina’s on the corner of Napoleon and Tchoupitoulas, and at the Village Vanguard on 7th Avenue and Perry Street, Minton’s in Harlem, the Green Mill in Chicago - and at The Bijou in Knoxville when Big Ears comes around.

“When you’re playing jazz, you can only play what you are.” _ Hilton Ruiz

I asked Workman about the 300 albums he has contributed his artistry to, and as soon as I started the conversation, we were wrapped in the fact that most of the people I referenced were gone.

He played on some of the most prized albums in my collection. “Fantasia” by Hilton Ruiz. “Orchestra: Duet and Octet” by Hamiet Bluiett. “Morning Song” by David Murray. “Juju” and “Night Dreamer” by Wayne Shorter.

On “Fantasia,” which was released in 1979 and dedicated to Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Workman played with drummer Idris Muhammad, tenor saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, trombonist Slide Hampton, and the brilliant young pianist Ruiz. As soon as I mentioned the album, I realized that Workman was the only contributor still living. He said, with an all-embracing wisdom, “You have to realize that as you grow older, you leave a lot of people in your wake. So many people I’ve worked with have jumped off the planet. Nothing is forever.”

I asked Virelles, the Trio’s uniquely inventive pianist, if it makes his head spin to play every night between two legends, both of whom are more than twice his age.

“Of course it does! As you mentioned, the collective discography of Andrew, Reggie, and Oliver (Lake) is the Mount Everest of this music," he said.

“Getting a chance to learn and play with the elders, both in the community where I grew up in Cuba and also in the community that adopted me in NYC, has been one of my main goals since a very young age. These guys are my inspiration, my role models. They’re some of the greatest musicians in history and an example of strength, self-determination, and perseverance. If I have a life in music, it’s thanks to the work of people like Andrew, Reggie, and Oliver.

“I consider Andrew to be one of my mentors. This list also includes Barry Harris, Stanley Cowell, Henry Threadgill, Muhal Richard Abrams, and Milford Graves. I also apprenticed in Steve Coleman’s band for five years, on and off," he said.

I realized Virelles was laying bare the sacred heart of jazz. Every name on his list of mentors represents a whole chapter in the history of jazz. And he was answering Kelley’s doubts about the future.

“For me,” the pianist continued, “community is only a part of it. In fact, I believe it’s bigger than the present community. This history goes back a long time. People like Mario Bauzá pioneered experimentation between Cuban musicians and some of the architects of Black American Music. I feel I’m part of the continuum that Bauzá fathered, and my goal is to contribute to that lineage.”

Bauzá, who was considered a child prodigy on clarinet, visited NYC in 1926 when he was 15 and stayed with his cousin who lived in Harlem. He played jazz in a band that included Cuban, Panamanian, and Puerto Rican cohorts. Bauzá was moved by the community in Harlem and the sense of freedom among the Black Americans there. He also happened to go to a concert and experienced George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” That’ll light the fire in any kid’s heart, and when Mario went home to Cuba, he vowed to return to the NYC jazz world. Before he was 30, he was in Cab Calloway’s band and jamming with Dizzy Gillespie and Ella Fitzgerald. By the start of World War II, Bauzá’s band Machito and His Afro-Cubans had established Latin jazz and its African-Caribbean roots as essential to American jazz and its values.

“Cuba and Black America have shared roots, and this is just one of the reasons I believe these collaborations are organic. They are meant to happen. They’ve been happening for a long time, and they have shaped the sound of the music of both countries," he said.

This music, these values are a beautiful thing. They are indeed meant to happen. And what makes jazz so different from rock and Americana music, from folk and punk and country, and even classical music, is the value placed on the cats you hang out with. The longer your resume, the more you bring to the bandstand.

OK, the same can be said to a certain degree about classical musicians, and bluegrass musicians. But musicians in orchestra chairs and pickers at the Ryman aren’t cats, and their resumes are narrower. And forget about rock bands. The members of Trio Imagination have played in hundreds of bands, with thousands of other musicians. The thought of looking at Mick Jagger and playing “Brown Sugar” every night would drive them insane.

Workman is worried that the demise of vinyl LPs and the instant access of YouTube have combined to wither the roots his music depends on. He teaches at The New School in NYC, and he established a school in Montclair, New Jersey, with his wife Maya, The Montclair Academy of Dance/Laboratory of Music, to help raise artists “that are awake.”

“Kids now can find any music ever recorded just by pushing a button on their telephone, and they can listen to the sound, but they don’t know who these people are that they’re listening to, and they don’t know what was going on in the world when the music was laid down. They don’t get the depth, the feeling. They’re not combing through record stores to find something new like we did," he said.

Forty years ago, I met a professor of art history at Yale named George Kubler. He wrote a book called “The Shape of Time” that continues to illuminate things for me, including Workman’s place in the history of jazz.

Kubler wrote, “When a specific temperament interlocks with a favorable position, the fortunate individual can extract from the situation a wealth of unimagined consequences. This achievement may be denied to other persons, as well as to the same person at a different time. Thus every life can be imagined as set into play on two wheels of fortune, one governing the allotment of its temperament, and the other ruling its entrance into a sequence.”

That just means you can cash in if you’re the right person in the right place at the right time.

When the 24-year-old Workman was asked to join John Coltrane’s band in NYC, he said “I didn’t realize the power of that band. (Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, and Elvin Jones) I didn’t realize how much energy it took to meet them on the plateau they had climbed to. Naturally I tried to keep up with the evolution of what they were doing, but it took so much energy, it was so powerful. McCoy was gracious enough to practice with me and help me learn the things I needed to learn, because John hardly ever told me anything. He expected you to know what his music was about.”

He expected you to know.

“Master your instrument. Master the music. Then forget all that bull and just play.” _ Charlie Parker

History is a living thing. And it plays at Big Ears.

John Job is a longtime Oak Ridge resident and frequent contributor to The Oak Ridger.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Trio Imagination coming to the Big Ears Festival