If Michael Jackson is canceled, can we still enjoy the Jacksons?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

To listen to the music of Michael Jackson in the year 2021 is to enter a moral thicket. The 2019 documentary “Leaving Neverland” told the stories of two men, Wade Robson and James Safechuck, who claim they were sexually abused as children by Jackson. Robson and Safechuck’s testimonies lend further credence to allegations and criminal charges that dogged Jackson during the last decades of his life. (In a 2005 criminal trial, Jackson was acquitted on 14 charges in the alleged molestation of another boy, Gavin Arvizo, and Jackson’s family and estate maintain that there is no truth to any of the multiple accusations against the singer.)

In the aftermath of “Leaving Neverland,” some have made the case that Jackson’s music should be banned, or shunned — that the least we can do for those who say that Jackson victimized them is to de-platform their alleged abuser. There are those who may regard a newspaper article about Jackson’s music as tasteless, or worse.

Alongside the moral issues, there is an ontological muddle. Music is a hard thing to cancel. It haunts our daily lives, whether we like it or not; it literally floats through the air, wafting down drugstore aisles and blasting out of passing cars. It’s difficult to conceive of the logistics by which “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” or “Man in the Mirror” could be suppressed. But if somehow you were to purge the planet of Jackson’s music, Jacksonism would remain.

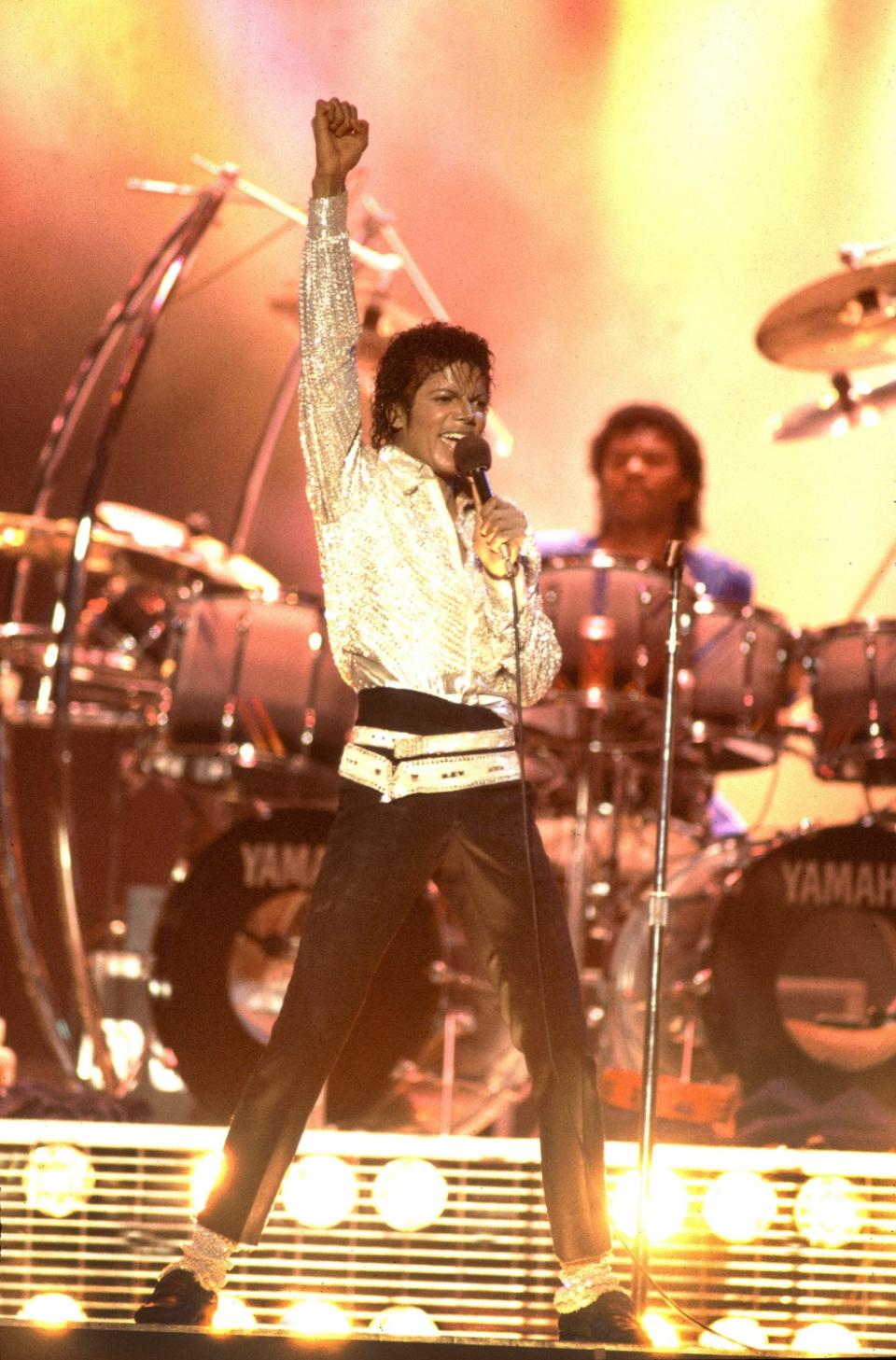

Jackson, who died in 2009 at age 50 from a fatal mix of medications, was the definitive pop star of the last two decades of the 20th century; he transformed music, and the recording industry, in countless ways. To the extent that Taylor Swift, Drake, Bad Bunny, et al. are not just beloved recording artists but global multimedia brands, they inhabit a universe that Michael Jackson made. A preteen pop fan, who was born after Jackson’s death in 2009 and may never have heard one of his records, knows his music anyway. If you listen to the Weeknd’s strobe-lit ‘80s-style R&B or Dua Lipa’s disco-funk, you’re hearing MJ secondhand.

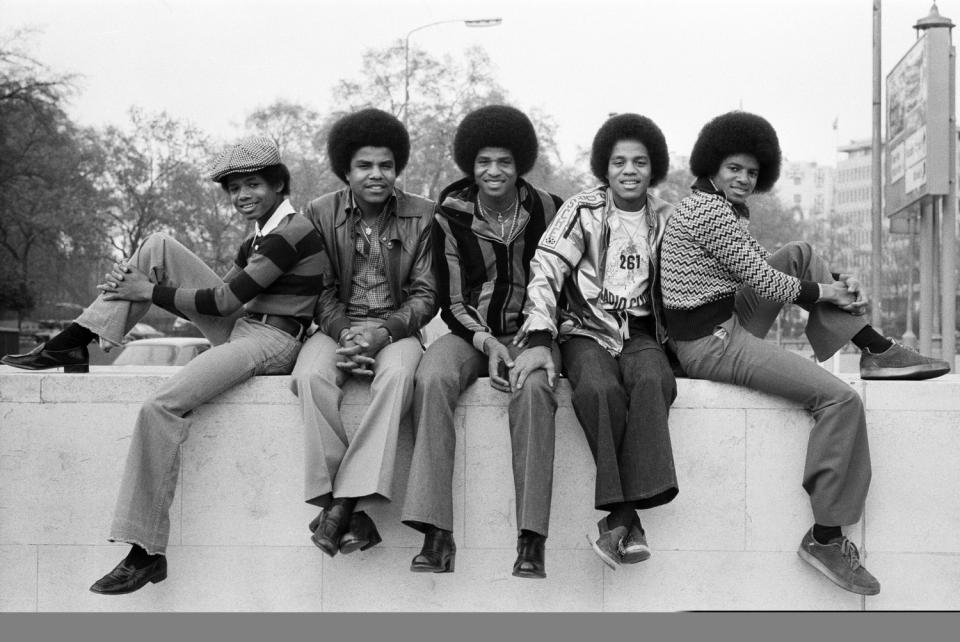

In any case, Jackson isn’t quite canceled. In February, his old record company, Epic, and Legacy Recordings, the catalog division of Sony Music Entertainment, began releasing expanded digital versions of all six studio albums by the Jacksons, the group that Michael and four of his brothers formed in 1975 following the departure of the Jackson 5 from Motown. The publicity push that has accompanied these reissues reflects the delicacy of doing Michael Jackson business, post-“Leaving Neverland.” Press releases describe the Jacksons as “avatars of an R&B/pop revolution,” while making only passing mention of the group’s lead singer, star attraction and creative driving force.

There is no denying the historical significance of the Jacksons’ output, or the fact that it has faded in public memory, eclipsed by both the widely beloved Jackson 5 records and by Michael’s titanic solo career. The music of The Jacksons was the bridge between these two eras. Their six albums — “The Jacksons” (1976), “Goin’ Places” (1977), “Destiny” (1978), “Triumph” (1980), “Victory” (1984) and “2300 Jackson Street” (1989) — are period pieces that mark the shifting sound of Black music, as ‘70s soul gave way to disco and then ballooned, in the steroidal ‘80s, into pop that strove for global dominion. You could also simply say that the albums document the emergence of a new genre — one we may as well call “Michael Jackson.”

The story begins, like many record business sagas, with warring lawyers. In July 1975, Joe Jackson, the Jackson paterfamilias, held a news conference in New York to announce that the Jackson 5 were leaving Motown to sign with Epic, a CBS Records subsidiary. Motown had made the group stars, but, according to Joe Jackson, it had not made them rich, or not rich enough, given the income they were generating for the label. The move to Epic brought a breach-of-contract suit from Motown, which eventually won the rights to the name Jackson 5.

The plot was further thickened by a familial soap opera. Two years earlier, Jermaine Jackson, the group’s heartthrob and co-lead singer, had married Hazel Gordy, the daughter of Motown founder Berry Gordy. Jermaine opted to stay with Motown to pursue a solo career. A younger brother, Randy, was conscripted as a replacement, and the band was rechristened the Jacksons. In November 1976, a self-titled album arrived in stores.

The LP was touted as a breakthrough. The Jacksons had grown weary of the Motown factory system — the strict control of songwriting, production and other aspects of art and commerce exercised by Gordy and his amanuenses. At a time when many Black stars, including marquee Motown acts like Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, were producing ambitious album-length experiments, the Jacksons felt stuck, typecast in a teenybopper role they had outgrown and doomed to a future of churning out albums on an old-fashioned hits-and-filler model.

Yet “The Jacksons” was hardly a radical swerve into new territory. For one thing, the group had not so much discarded its Svengalis as switched them up. The album was a joint venture between Epic and the label Philadelphia International, co-founded by the songwriting and production team of Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff. Gamble and Huff executive produced “The Jacksons” and wrote five of its 10 songs, and it sounds like it — the music is a jauntier, somewhat ungainly version of the duo’s lushly orchestrated Philly soul sound. Beneath the grooves we can detect marketing, a reassuring message aimed at Jackson 5 fans and, perhaps, their parents. The story is told by the song titles: “Enjoy Yourself,” “Think Happy,” “Good Times.”

“The Jacksons” went gold and spawned two hit singles, but it lacked the bite and excitement of the best Jackson 5 music. The most noteworthy song was the most unassuming: “Blues Away,” a loping mid-tempo vamp, nudged forward by Fender Rhodes and brass and strings, and delivered with breezy confidence by Michael, who had turned 18 that August. “Blues Away” was Jackson’s first solo songwriting credit, and it held hints of things to come. Sonically and harmonically, it’s a near-dead ringer for the lead single from “Thriller” (1982), the Paul McCartney duet “The Girl Is Mine.” But the real revelation is Jackson’s singing. The feathery falsetto, the tremulous vibrato, the percussive gasps and whoops — the vocal style that would captivate the world in a few years’ time was drifting into earshot.

You could say it was the sound of a singer aging in reverse. On the Jackson 5’s smash 1969 debut “I Want You Back," Michael was an 11-year-old impersonating a soul man, emoting in the burly style of Wilson Pickett and Levi Stubbs. On “Blues Away,” Michael had slid into his upper register, and a childlike breathiness had seeped into his voice. The blend of sweet and rough — the high, guileless, often plaintive tone of Jackson’s pure singing voice interjected with hiccups, “hee-hees” and other grunts and respirations — is arresting and strange, a sound that didn’t exist before Jackson. Not even James Brown had conceived so original a way to disrupt melody with funk, and vice versa.

Jackson’s vocals tilted increasingly in this direction on “Goin’ Places,” again produced by Gamble and Huff. It was a solid effort, but it stalled at No. 63 on the Billboard 200 album chart in November 1977, and none of its three singles cracked the Top 50. Michael’s own commercial slump was now a half-decade deep. His four Motown solo LPs, released between 1972 and 1976, had met with progressively diminishing sales. His biggest solo hit, “Ben,” from 1972, was the maudlin theme song from a movie about a pet rat. (The song was given to Michael when Donny Osmond couldn’t fit a recording session into his schedule.) “Goin’ Places” marked a low point: the moment when it seemed possible that the Jacksons, and their supernatural frontman, might stall out, as numerous former child stars had before them.

Salvation came from opportunism. “We spent the night in Frisco / At every kind of disco,” Michael sang on “Blame It on the Boogie” (1978). The “Saturday Night Fever” soundtrack had spent more than half of 1978 at the top of the charts, and the Jacksons wanted in on disco fever. “Destiny,” released that December, hit pay dirt. It was the Jacksons’ first self-produced release, and all but one of the songs were written by Michael and his brothers. The tour de force was “Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground),” a celestial song about the earthy pleasures of dancing, which fizzed and percolated for a full eight minutes in the version included on the album.

The secret of the Jacksons’ disco was that it wasn’t quite disco. “Blame It on the Boogie” and “Shake Your Body” were lightly discofied funk; they were songs about disco, sung by an absurdly charismatic 20-year-old who had taken to wearing spangled pantsuits and socks, like a human mirror ball. (The spangled glove would come a couple of years later.) A fair percentage of all the pop songs ever recorded have been entreaties to hit the dance floor, but few have made the glory of moving your body to music so irrefutable. The fact that Jackson was one of the world’s best dancers helped to seal the deal. Even if, in that pre-MTV moment, fans couldn’t see Michael’s moves, they could hear them: in “Shake Your Body,” his singing transmuted the razzle-dazzle of his twirls and kicks and gyrations into sound. The Jacksons had found their niche and, as the poet said, the boogie was to blame.

To revisit the Michael Jackson of “Destiny” is to encounter a person that has become distant to us. He was a star but not yet the star. The sleepovers with children at Neverland Ranch, Bubbles the pet chimp, the cosmetic surgery that did violence to his beautiful face — all that weirdness had not yet manifested. Paparazzi captured photos of Jackson on nights out at Studio 54: a suave and princely figure, gliding, it seemed, through the normal unreality of celebrity existence. This was the dapper young man who appeared in a tuxedo, flashing a blinding smile, on the cover of “Off the Wall” (1979), the solo masterpiece that sold millions and secured his superstardom.

The success of “Off the Wall” might have done the Jacksons in. But to narrate the Michael Jackson story as a heroic progression from “Off the Wall” to “Thriller” and beyond, is to omit a crucial milestone. “Triumph” (1980) was the Jacksons’ best album, and it contained Michael’s most novel work to date, the kind of farseeing, genre-busting music that would eventually justify the honorific King of Pop. In songs like “Everybody,” “Walk Right Now” and the irrepressible “Lovely One,” The Jacksons’ continued their post-disco refurbishing of the dance jam. But other songs aimed higher and wider, and a dark grandeur crept in.

Exhibit A is the hit “Can You Feel It.” With a booming arrangement tinged by funk and rock, and lyrics that envision peace and love on a cosmic scale, “Can You Feel It” anticipates the bombast of Michael’s post-“Thriller” period: the messianic songwriter behind “We Are the World” (1985) and “Heal the World” (1991) is limbering up. The “Can You Feel It” video, a sci-fi mini-epic, cast the Jackson brothers as extraterrestrial deities who descend from the heavens and sprinkle fistfuls of stardust on Planet Earth’s huddled masses.

Then there’s “Triumph’s" centerpiece, “This Place Hotel” (originally titled “Heartbreak Hotel”), a song as gripping — and as bonkers — as anything Michael recorded in his solo career. It tells the story of a young man who arrives at a hotel with his girlfriend, only to discover that his room is infested by “wicked women,” including a number of ex-girlfriends. The guy is dumped by his lover, and he spends the rest of his days lamenting his visit to “this place where the vicious dwell.” It’s a preposterous plot line, but the music, a kind of goth-funk, is exhilarating, and if you listen past the B-movie campiness, you hear genuine terror. “As we walked into the room / There were faces / Staring, glaring, tearing through me,” Michael wails. The misogyny, the sexual paranoia, the conviction that fame itself is a haunted house that entraps and devours its inhabitants — these themes would surface again and again in Jackson’s music.

The most famous example, of course, is “Billie Jean,” the signature hit from music’s biggest blockbuster. After “Thriller,” any pretense that the Jacksons were co-equals collapsed. To Michael, the brothers were a burden; to the public, they were, at best, superfluous. Jermaine rejoined the group for “Victory,” released in July 1984, at the height of Michael’s imperial phase. Recording sessions for the album were reportedly tense, and the results were turgid. On the tour that followed, Michael traveled between concerts on a private jet while his brothers flew commercial. During the tour’s final show, at a rainy Dodger Stadium on Dec. 9, 1984, Michael announced, apparently to his brothers’ surprise: “This is our last and final tour … it’s been a long 20 years.”

The question of what, exactly, Jermaine, Randy, Marlon, Tito, and Jackie brought to the table, besides the competence of showbiz lifers, is one that the Jacksons reissues do little to resolve. The four “Victory” songs on which Michael does not appear are, to be kind about it, unremarkable. “2300 Jackson Street” was drearier still. The album was released in 1989, by which point the group had been reduced to a quartet, Marlon having departed along with Michael. The remaining Jacksons recruited top producers, including Teddy Riley and L.A. Reid and Babyface, but the à la mode New Jack Swing beats did not disguise the pallid songs and performances. The title track was a self-mythologizing ballad that tried to paper over the family tensions with bromides: “We’re all united / And standing strong / And still today / We’re one big family.” Michael makes a guest appearance on the song, as does another notable Jackson: sister Janet, whose “Rhythm Nation 1814” album, released that same year, proved that there was more than one superstar in the family.

Today, a decent argument can be made that Janet has a more convincing, more consistent discography than her late brother. It is certainly a less fraught body of work. It does not call upon a music fan to make a careful calculation of moral math, to reckon with all that history, before clicking play on a streaming link or hitting the dance floor. A Janet Jackson record affords a simple privilege which, for the foreseeable future, even the most joyous song by Michael Jackson does not: You can listen to the music and not hear the noise.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.