We must remember that White House history is Black history. This is some of that story.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves.”

First lady Michelle Obama’s 2016 words captured the horrifying wrongs and hard-won achievements that epitomize the story of Black history at the White House. The unfolding of our country’s history with slavery, at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue and its surrounding streets, is critical for all Americans to understand.

Black men and women were first brought as captives to the colony of Virginia in 1619. By the time what is now Washington, D.C., was founded in 1790 on land ceded by two slave states, more than 680,000 people – nearly 1 in 5 Americans – were enslaved in the new republic.

Slavery and the White House

At least 10 enslaved workers were assigned to President George Washington’s homes in New York and Philadelphia while the president’s house was being built, and they were often separated from their families living at Washington's Virginia plantation at Mount Vernon.

One of them, Ona Judge, escaped by ship to New Hampshire (and evaded attempts at recapture) after learning of plans to give her to one of Washington’s granddaughters as a wedding present.

Opinions in your inbox: Get exclusive access to our columnists and the best of our columns

A free Black man, Benjamin Banneker, helped map the boundaries of America’s new capital city. In a letter, he urged future president Thomas Jefferson to broaden his concerns beyond British oppression to include Black Americans. Banneker published their correspondence to advance the national dialogue around the abolition of slavery.

Slavery has been part of White House history even before anyone moved in. For eight years, more than 200 enslaved people were forced to help every aspect of the construction of the White House, working with immigrant laborers, craftsmen, European artisans and local contractors to quarry stone, cut timber, make bricks and raise walls and roofs.

In the decades that followed, 11 of our first 12 presidents either brought enslaved people with them or relied on enslaved labor at the presidential households in New York, Philadelphia and the White House. They worked as chefs, valets, gardeners, coachmen, butlers, lady’s maids, stable hands, landscapers and more. Most slept in the attic or in ground-floor rooms that were often damp and infested with pests.

These men and women often had to struggle for the smallest freedoms. William Custis Costin – who might have been first lady Martha Washington’s grandson – unsuccessfully challenged local laws requiring freed Black people to carry special credentials.

And when Virginia law threatened to reenslave Melinda, the freed wife of enslaved servant John Freeman, he beseeched President Jefferson to prevent his family from being split up as the departing president prepared to move back to Monticello. Jefferson sold Freeman and his debt to incoming President James Madison so that the family could stay together.

Black history is American history: We must face facts, face fears and face forward

The anti-slavery movement

Paul Jennings, who was enslaved in the Madison and Polk White Houses, assisted the daring 1848 getaway of 77 enslaved people aboard The Pearl, a schooner docked just 2 miles from the White House. The attempt failed, everyone was recaptured and the organizers had to be hidden away during three days of angry pro-slavery riots. But the episode fueled the growing anti-slavery movement in the United States.

President William Henry Harrison’s Black valet George DeBaptiste was an important figure in the underground railroad, helping 180 people escaping across the Ohio River from slavery in Kentucky, buying a steamboat to ferry others to Canada and recruiting Black soldiers to fight for the Union in the Civil War.

Carrying baggage from our ancestors: My great-great-grandfather owned slaves in Kentucky. Here's what I'm doing about it.

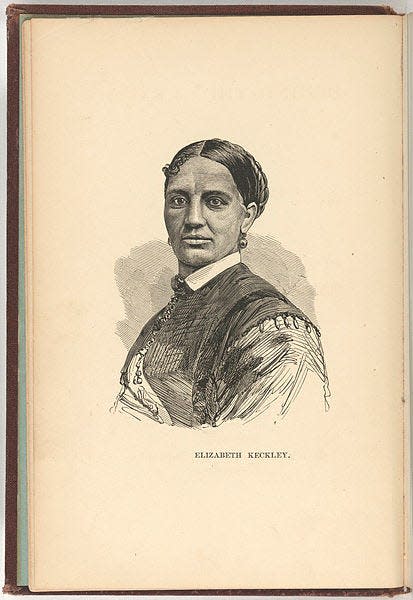

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly rose from slavery to raise money as a seamstress to self-emancipate, later becoming a dressmaker for first lady Mary Lincoln. She tended the Lincolns’ dying son Willie and comforted them after his death. (Keckly’s own son George was killed during the Civil War fighting for the Union.) After the president was assassinated, Mrs. Lincoln called Keckly to her side.

After Lincoln signed a law emancipating enslaved people in the nation’s capital (and compensating their owners), Elizabeth Keckly created a charity to support the refugee camps where many of the newly freed people gathered. Many were clothed in rags, slept on bare floors and suffered from measles, typhoid and scarlet fever. President Lincoln passed them in his carriage each day, and at Keckly’s urging the Lincolns donated to the camps throughout the Civil War.

Another formerly enslaved person, Frederick Douglass, became one of America’s most influential figures. He endorsed Lincoln in the crowded 1860 election, visited him at the White House, and was an important influence on the president’s transition from generally opposing slavery to taking steps to actively abolish it.

“There is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours,” Lincoln told him after his second inaugural address. “I want to know what you think of it.”

The refugee camps swelled further after Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation – signed 160 years ago this winter – outlawed slavery in the eight Confederate states still in rebellion. Refugees were put to work (at substandard wages) as construction workers, cooks, hospital orderlies and street cleaners.

New planned communities were built, including Freedman’s Village on the confiscated estate of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee.

Not 'just' hair: For Black women, hair is about our ancestry, our being, our identity

Listening to Black voices

White House history is Black history, and it is critical that the Black voices of White House history be heard. That’s why the White House Historical Association has been researching this history since 2016 and launched the "Slavery in the President’s Neighborhood" initiative three years ago. We’re working to move these individuals to the forefront of White House history, through letters, newspapers, memoirs, census records, architecture and oral histories.

There are so many more stories to tell: not just to better understand the slavery era, but also the history of the struggles and achievements of Black Americans that followed.

Opinion alerts: Get columns from your favorite columnists + expert analysis on top issues, delivered straight to your device through the USA TODAY app. Don't have the app? Download it for free from your app store.

As Mrs. Obama put it, this is “the story of generations of people who felt the lash of bondage, the shame of servitude, the sting of segregation, but who kept on striving and hoping and doing what needed to be done.”

Not long after the Obamas came to live in a White House built in part by enslaved laborers, they hosted a ceremony for the descendants of Paul Jennings – a Black man who helped save the iconic painting of George Washington from the British as they prepared to burn the White House. (The same Paul Jennings who later tried to help freedom seekers in the nation’s capital on The Pearl.)

In 2009, dozens of Jennings’ family members came to visit the Obamas and see the house where their ancestor had worked as an enslaved butler and valet. Before they left, they stood for a family photograph – in front of the painting of George Washington that Jennings helped save.

We can’t change or ignore the hardest parts of our history. By keeping the truth about these struggles and achievements alive, one story at a time, we can help ensure the White House truly is “The People’s House.”

Stewart D. McLaurin, a member of USA TODAY's Board of Contributors, is president of the White House Historical Association, a private nonprofit, nonpartisan organization founded by first lady Jacqueline Kennedy in 1961.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: White House history is Black history. These are America's stories.