We must stop blaming mass shootings on America’s mental health crisis. Here’s why | Opinion

In early August, Nathan Cruz — the cousin of the Uvalde school shooter from May of 2022 — was arrested after attempting to illegally purchase an AR-15 and “do the same thing.”

Mass shootings (defined as four or more shootings in a single place) are so common in the United States that we have accumulated a database run by the National Institute of Justice. By averaging more than one every day, we have learned a lot about the mass shooter.

We know that fewer than 5% of the 120,000 gun-related killings that occurred in the U.S. between 2001-2010 were perpetrated by individuals with a mental illness, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Opinion

“Studies show that the mentally ill do present a higher risk for violence than others, but overall they account for just 3-5% of violence in the country — and only 1% of gun violence against strangers,” a 2016 Washington Post article states. “They are far more likely to be victims of crime.”

America has a mental health crisis and a gun crisis but conflating the two only allows serves to give the gun industry a pass on its complicity as the bodies of mass shooting victims pile up. Making the gun crisis about mental health is a reliable GOP talking point that prevents meaningful gun reforms.

The book “The Violence Project: How to Stop a Mass Shooting Epidemic” argues that students who become school shooters are often the victims of extreme bullying, rejection from peers, isolation and self-loathing. It ends when their hate turns outward toward classmates, religious groups, immigrants or anyone else they can blame. The authors have a $50 billion solution: hiring 500,000 psychologists.

Suicidality is a strong predictor of who might become a mass shooter: 30% of mass shooters report they were suicidal before their shooting, and another 39% during their shootings, according to the National Institute of Justice. School age shooters, using guns taken from family members, are almost always suicidal. We should better fund suicide prevention programs.

Most shooters are men with prior criminal records (64.5%) and a history of violence (62.8%), also according to the National Institute of Justice. They have ready access to firearms. At least 36% of mass shooters have been trained by the U.S. military. Many act as if they’re still in the military, waging their own delusional wars against people of color, immigrants, Jews or other groups. Many of them went to war to kill, received the training to do so and still have that urge. They use military weaponry when they kill, and many still dress in their military clothing. We have laws keeping dishonorably discharged men from owning guns but we can’t stop them from stealing one.

UC Davis Vice Chairwoman of Community Psychiatry Amy Barnhorst said it best in a New York Times op-ed: “there is no reliable cure for angry young men that harbor violent fantasies.”

What can we do? The most common sense step would be to make access to firearms more difficult for at-risk men, an idea opposed by the powerful gun lobby.. Since four-fifths of shooters make their intentions known via social media or directly to their family, often leaving a written record or manifesto, we can educate families and co-workers about red flag laws and how to recognize warning indications. Alerted families can seek gun violence restraining orders from a court.

That’s exactly what the mother of Nathan Cruz did when she learned that her son planned to buy an AR-15 rifle. Nathan was arrested, and the targeted school in San Antonio was spared. Red Flag laws work well in 19 states when law enforcement agencies are adequately trained and willing to petition the court and people know such laws exist.

The erratic behavior of Robert Card, the perpetrator of the recent mass shooting in Lewiston, Maine, concerned U.S. Army Reserve officials so greatly that they alerted police, who took him to a psychiatric hospital in July. He was banned from handling weapons at his home base, and army officials alerted local police to his behavior.

A fellow soldier had even texted: “Card is going to snap and do a mass shooting.” Every factor needed to invoke Maine’s yellow flag restrictions were present. Yet, one was never implemented.

Only two red states, Florida and Indiana, have passed red flag laws. Florida enacted a red flag law in 2018 after the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School massacre. In the following years, their courts handled 8,100 red flag petitions. There’s no knowing the number of mass shootings those petitions prevented.

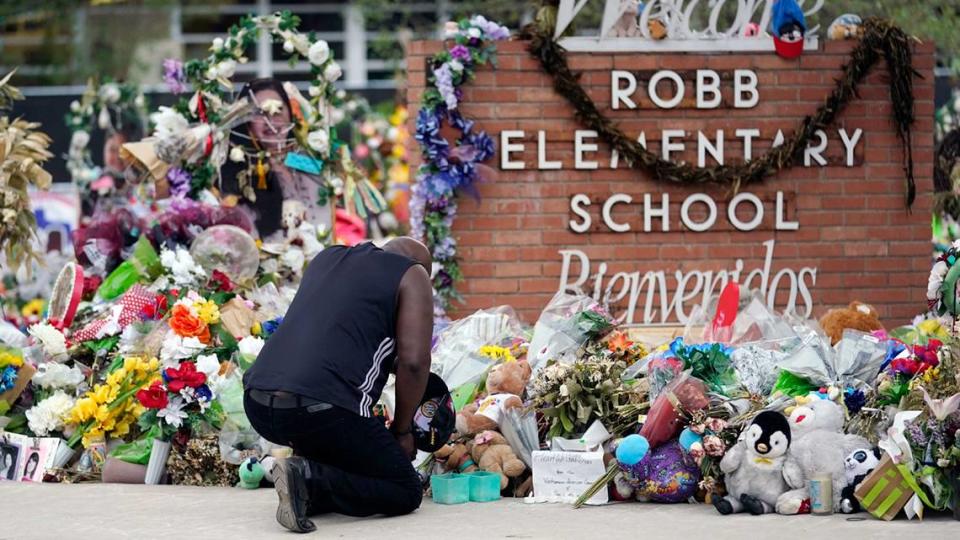

After the Uvalde massacre, the Texas legislature put the blame on liberal “wokeness,” fatherless families and video games but refused to raise the age to purchase a gun from 18 to 21. Doing so would have made it harder for Ramos to murder 21 people and injure another 17.

Calls for improved mental health services and better school security are the standard responses. We have been there and done that. They didn’t help the Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, a school with state-of-the-art security and a full-time armed guard.

After mass shootings, we find ourselves doing the same thing and expecting a different outcome. That fits the common definition of insanity. So, at long last, there’s your mental health diagnosis.

Gilbert Simon, MD, is a professor at the California North State College of Medicine and the author of “Ripped Off! Overtested, Overtreated and Overcharged: The American Healthcare Mess.”