‘Year of the Mustang’: One man’s mission to remind us of the plight — and power — of the wild horse

Six-year-old Denver’s ears flicked back and forth and his dark, shiny coat rippled with tension each time Jake Harvath bumped a heavy leather pack against his sides.

Jake was gently testing his youngest mustang’s memory of what it was like for a 65-pound pack to hang against his rib cage. At first, Denver flinched each time his human partner heaved the bag up, then down, up, then down. He stood still, eying Jake with more trust than uncertainty until he no longer quivered. Eventually, Jake clipped two of those packs to Denver’s saddle, one on each side.

Now to test him in movement. Denver trotted steadily around Jake until the packs bouncing on his back spurred his instincts to take over and his legs lurched out from beneath him in fear. He fought to break out into a gallop, but Jake firmly jerked the mustang’s haltered head in to keep him under control in a tight circle.

“It’s kind of like a high-fiber breakfast,” said Jake’s dad, Daniel, as he watched his son work Denver from behind the tall round pen fences at his home training facility, Sage Creek Equestrian, near Heber City, Utah.

“It’s not always easy to watch, but it’s really good for Denver. In the long run, it will help him feel calm and at peace. A lot less fear,” Daniel Harvath said. “These creatures, being herd animals, their biggest challenge is fear. At the core, that’s all Jake is trying to teach them, to work through fear.”

Jake is going to need Denver and his two other mustangs to overcome a daunting challenge of his own — a more than ambitious solo pack trip to crisscross America that he’s been planning since he was a teenager.

The journey: a multi-state backcountry horseback ride spanning 7,000 miles from Utah all the way to New Jersey, then all the way back to California before returning to Utah. Jake’s goal is to complete this trek within a year.

He’s named this endeavor the “Year of the Mustang.” He’s documenting it all on his YouTube, Instagram, Facebook and TikTok pages with the help of his friends and family to download, edit and post videos from his GoPro whenever he’s able to connect to the internet. He also organized a GoFundMe page for the endeavor, for which he’s raised over $4,800 so far.

If he’s able to pull it off, Jake hopes to set a record for the longest horse pack trip ever done in the U.S. in a year’s time. But that’s not the main reason he’s doing it. Most of all, he wants to remind us of the power of the horse — how it helped settle the West — but also raise awareness of the modern-day plight of the wild horse.

A man and his mustangs

As he watched, Jake’s father didn’t say much, but he emanated pride. His son got himself into horsemanship at the age of 12 by learning to team rope with his neighbors, then at 14 started working at Sage Creek Equestrian’s barn in exchange for riding lessons after his mom found a help wanted ad. Then at 15, Jake’s boss gave him his first horse as a Christmas gift. Jake also learned to become a farrier. He shoes his own horses and built up a clientele so he could earn a living.

Everything in Jake’s life has revolved around horses. “He’s just been at it so long, it’s just become a part of who he is,” his dad said.

Around and around Denver went until eventually his mind settled. He stopped, took a deep breath, and licked and chewed — a telltale sign that a horse is learning, relaxing and submitting. Denver was still learning how to be a pack horse. And he was just weeks away from the day it would become his life, day and night.

Nearby, Jake’s two other mustangs stood quietly tethered. There was the expert, Bella, a 16-year-old mare with a speckled white coat. She was Jake’s most trusted companion, his first horse, his teacher. Then there was Eddy, a 12-year-old veteran trail horse but a newcomer to Jake’s herd. He was a bulky, dark bay gelding with a white blaze the shape of South America on his forehead. He was strong and experienced, but still learning to trust and respect Jake’s lead.

Denver was the rookie — a recent graduate of a 100-day horsemanship competition to train Bureau of Land Management mustangs. Jake recognized Denver’s potential and brought him home from Nevada last year. Both Bella and Eddy were also BLM mustangs, Bella also from Nevada and Eddy from New Mexico.

Their wild origins matter, because it’s at the core of his “Year of the Mustang” mission, which he officially embarked on Sept. 25.

The wild horse crisis

Today, the Bureau of Land Management manages some 83,000 wild horses and burros across the nation, according to BLM estimates. Of those, over 64,000 are kept in “off-range” holding facilities, fed and cared for in either corrals or pastures. The BLM is charged with managing the population while balancing the “health and productivity” of public lands, which is also used for cattle and sheep grazing.

It’s a crisis in the West: a $5 billion wild horse problem with no real solution in sight. Government range watchers say the wild horse and burro population should be contained to just under 27,000, the Deseret News wrote in a 2019 in-depth special report, but the horses continue to quickly multiply.

Wild horse advocates rail against roundups and argue the mustang has been a scapegoat for damage caused by taxpayer-subsidized cattle grazing. The BLM, which also manages livestock, says in its efforts to balance the use and management of public lands, it allows grazing for only a permitted number of months while roaming wild horses and burros graze all year long. In some cases, the BLM has implemented fertility control, but treating and accessing the horses can be expensive and difficult. The agency has recorded a total of 8,530 treatments since 2012.

As part of its herd management, the BLM has also offered wild horses and burros up for adoption. Since 1971, the BLM says it has adopted out more than 270,000. The number of adoptions has grown over the years, from 2,583 in 2012 to 7,369 in 2021. Adoptions, however, dipped to 6,669 in 2022, according to the BLM’s website.

Related

To those who believe these mustangs should just be left alone to roam free, Jake said that’s not a real solution.

“As wonderful as that would be, we live in a country, in a modern society, that doesn’t allow that to happen,” he said. Public lands and their grazing offerings are limited. Meanwhile, land management and human development pressures simply don’t allow them to roam freely.

“Many of these horses out there are starving,” he said. “At least in BLM holding (they) get enough food to eat and regular water, compared to ... competing with other species, mostly us, to survive. It’s because of that, them just being wild, turning them all loose, isn’t really a solution.”

To Jake, adoption is the best and most humane answer to this thorny issue. He hopes his trek will not only educate about horses’ capabilities, but also inspire more people to consider the possibility of adopting their own mustang.

“These horses are absolutely worth adopting, they’re very trainable, and they are incredible partners,” he said in one of his YouTube videos. “What better way to showcase that than on a journey like this?”

Related

The horse used to be deeply ingrained in American life, from farming to transportation. But times change. Now, it’s a luxury to own a horse. Human population growth and development pressures are gobbling up agricultural land and horse property. There’s more fueling the problems facing mustangs than just cattle grazing and public lands management. It’s everything.

“It’s within the last 100 years that we’ve shifted away from them being everything for us in society,” Jake said. “And there’s a lot of history there that most people don’t know anything about today. But through this trip, they’re going to be able to watch what that was like for many of our ancestors on a daily basis: what it was like to live alongside horses.”

Maybe it’s idealistic or unrealistic, but Jake dreams of what could happen if the U.S. returned to its roots. If more Americans who have the land and financial resources could remember what the horse gave us and give it back. Be a home for a horse. Maybe then there would be fewer mustangs in holding pens and more lives made richer because of a horse’s special companionship.

“I know that through this my three horses are going to show the world that mustangs absolutely are worth adopting,” Jake said. “Everyone’s going to know it by the end of this year.”

Fear and doubts

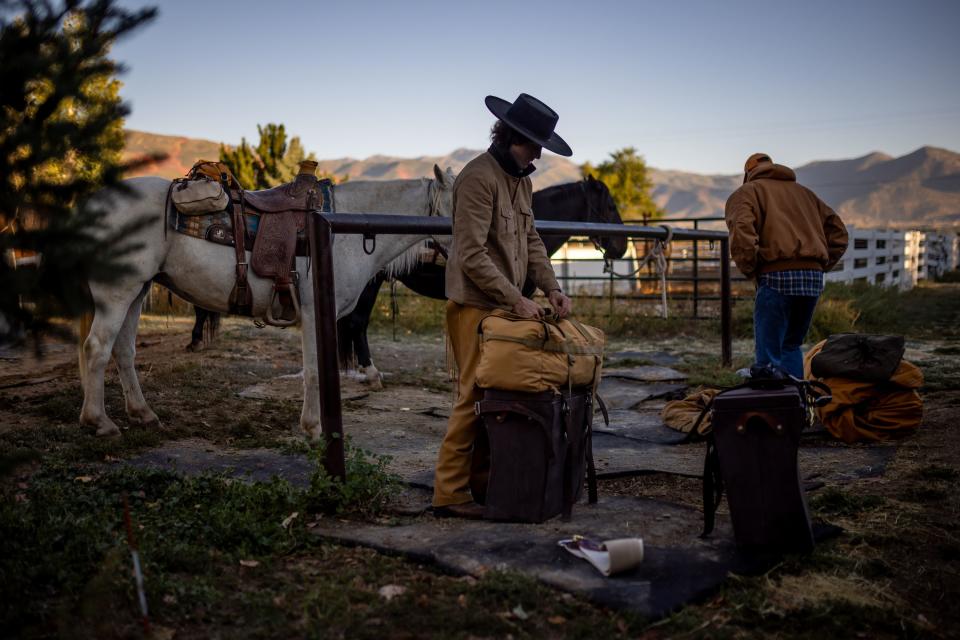

The morning of Sept. 25, a small crowd of family and friends bid Jake, Bella, Eddy and Denver farewell from their journey’s starting point at the horses’ home at Sage Creek Equestrian in Charleston.

It was sort of an anticlimactic beginning. With packs piled high on top of Eddy and Denver’s backs and Jake atop Bella, the trio clip-clopped across U.S. 189. In just a few short weeks, Denver was already looking like a pro pack horse. They passed through the town of Daniel, then headed into the backcountry toward Strawberry Ridge.

From then on, it was just Jake and his horses. Alone in the woods.

Weeks before, when I asked Jake’s dad what worried him most about his son going on such a lonely and daunting journey, he thought about it for a long moment — watching Denver lope around his son in a circle — before he answered.

“Getting stuck,” he said.

Daniel Harvath said he and his horse’s health and safety was first and foremost in his mind. But he shared his son’s ache to accomplish this goal that’s been all-consuming in his mind for so long.

“It’s not so much a fear,” Daniel Harvath told me. “I don’t think there’s anything that’s going to stop him. He’s not making any promises. It’s not a race, not a competition.”

And this journey wouldn’t be completely lonely. Daniel Harvath would be keeping tabs on his son’s GPS location, and he would have his phone. Plus, Jake spent years planning his route and creating a network of members of the horse community across the country that could lend their land, facilities and assistance along the way. For example, for the first leg of the journey, Jake didn’t pack a tent, planning on having one dropped off for him at some point before the first snow.

“I get messaged probably five or 10 times a day from people asking how they can help,” Jake said. “It’s so cool.”

If worst comes to worst — if one of his horses gets sick or injured — Jake said he’d find a way to continue on by turning to the horse community and borrowing a horse. He said it’s the “last thing I would ever want to happen,” but he’s prepared to put a horse out of its misery if it were to suffer a catastrophic injury like a broken leg.

“But there’s a lot of things we can overcome with rest,” Jake said.

Much of Jake’s work in horse training comes down to overcoming fear. For Denver, his fear of packs on his back soon gave way to habit. But just like his horses, Jake had his own fear to overcome — and it’s something horses have taught him too.

Bella, in particular, “taught me how to relax. How to relax when things are difficult.”

Jake puts those words into practice. When working with Denver, his movements are calm and meticulous. He’s quiet and soft-spoken. It’s hard to imagine him rushing into a task or falling into a panic.

But earlier this year, as he was preparing for the trip, Jake said he was almost immobilized by “fears and doubts” that kept rearing their head. He turned to God for help.

In the past, Jake said his faith has helped him overcome obstacles and make big decisions in his life. A member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he served a mission in Honduras until the COVID-19 pandemic broke out and he was assigned to Denver, Colorado (hence Denver’s name). But for the longest time, Jake said he “just couldn’t get an answer” from God on whether he should or shouldn’t go on this journey.

“I wanted the answer to be, ‘This is what you’re supposed to do. Go,’” Jake said. “I went out in the woods here in January and prayed, just with everything I had. And the answer was, ‘This is your choice. I’m not going to tell you to do it, and I’m not going to tell you not to. You have to decide for yourself.’”

That was “almost a harder decision,” Jake said.

“But now I look back and I’m starting to realize why it had to be my decision,” he said. “Because I found it in myself, my own innate desire, that this is all I want to do. This is what I feel I have to do. So I decided, I buckled down, and I’m not afraid to do it anymore.”

Jake said he also hopes to inspire other people his age — other young men and women who are “afraid to move forward and not be stagnant” — to push ahead, even if it’s scary.

“Even if you don’t have a massive dream in your life to pursue,” he said, “you should at least be pursuing something bigger than you are now.”

‘Every day is a gift’

We met up with Jake on his third day, in the mountains near Clyde Creek on the other side of Strawberry Ridge.

I heard him and his horses before I saw them. Bella, Denver and Eddy’s hooves clip clopped down a rocky road. They walked steadily and relaxed. Jake sat atop Denver, who led the pack with ease to a grassy field next to a pond, where Jake stopped to take a drink.

His horses hobbled and waited in the distance (appearing all too happy for the grazing break). Jake brushed his hand across the pond’s surface, pushing aside a frothy film of green algae to make way for his water filter. Slowly, he filled the blue bag up with water, then squeezed it through the filter into his canteen.

“Tasty, right?” he said before taking a swig. “Not bad.”

Jake’s face and forearms were a bit sunburned, but overall he appeared in good spirits. His horses were calm, cooperative. In their element. And so was he.

These first few days had been slow going — he hadn’t wanted to push the horses too hard early on and they were still “working out the kinks” while saddling up in the morning, so he hadn’t made it as far as he’d originally planned. But the previous night, Jake found a water source and a place for the horses to graze, and that’s all they needed.

Eventually, Jake hoped to work the horses up to 25 to 30 miles or more a day, but early on as the horses built their muscles he was keeping it about 15 to 20 miles a day. Though he’s still dead set on his goal to keep going for the year, Jake said he’s proud of what they’re able to accomplish, regardless of if it’s weeks or months.

“Every day is a gift,” Jake told me. “Whatever days I get will be invaluable, no matter what.”

Almost two weeks later, Jake posted a new video to his YouTube channel documenting the first 90 miles of his journey.

The first day was “tough,” he said. It felt “like any other pack trip, but not because there is no plan of going back the way I came. So I guess it’s different in the sense that this is just my life now.”

“One down and at least 365 more to go.”

Throughout the video, Jake’s chapped lips reddened, blistered and scabbed as he described his journey. One morning was “eventful,” as he put it. While he was making breakfast, something spooked Denver and he tore backwards, ripping his stake out of the ground. Eddy followed.

“Luckily I caught Bella and threw a saddle on her and made a mad dash after them,” Jake said. “It was a pain in the neck.”

Jake rode along Strawberry Reservoir, then into Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest, before dropping down near U.S. 6 and making their way toward the town of Helper. Next, Jake planned to head toward Green River, hoping to make it to Colorado within the next week and a half.

In Helper, he planned to take a shower for the first time in two weeks thanks to a family that let him and his horses stay on their property for two nights while they got some much needed rest.

“Not going to lie, I needed it,” Jake said, calling the first two weeks “absolutely insanely difficult.” But he said during the last couple of days “things have been looking up, the horses are starting to figure their job out, they’re working really hard, looking really good.”

Along the way, the horses “are definitely turning more into my family, even more than they were before.”

Jake set a goal for himself in the month of October: Be “honest” and get “serious about what’s got to happen, what’s got to change. I’ve learned a lot of lessons in these first few weeks that just made me rethink how this whole trip’s going to go, and how I’ve got to do things in order to keep the horses healthy and keep me safe and have less problems along the way.”

“We’re two weeks in. We’re moving slowly but we’re moving,” he said. “I’m grateful for the lessons even if I have to learn some of them the hard way. It’s part of life.”

Ninety miles down and over 6,900 to go, Jake still wasn’t letting fear or doubts stop him.

“Here’s to many more miles of fantastic country to see.”

Related