Myriam J.A. Chancy on What We Can Learn from Haiti

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

August 14, just a little over a month after the assassination of the Haitian president, a magnitude 7.2 earthquake rocks Haiti, a small island nation shaped like a scorpion's claw. Unlike the last one in 2010, this one erupts in broad daylight: The damage is clear and immediate. By evening, Haitians across the country decide to sleep in their yards, wherever they can find open space; some by choice, others not. Haitian friends post about the pain of being Haitian. Wherever they find themselves, most don’t sleep, or, if they do, they are dreamless.

On the evening of August 16, tropical storm Grace makes landfall and the thousands sleeping under the stars have nowhere to turn. Those with tarps lose them to the winds. An uncle sends me coverage by a local journalist showing an elderly woman trying to make her way across a field after her makeshift shelter blows away. I can’t watch this, he says, as he sets down his microphone and asks his cameraman to help. They pick up the woman like a child and yell to those nearby to take her in. Others, especially those in far-flung towns and villages beyond Les Cayes, will remain inaccessible, will be waiting for food, shelter, clothing, medical aid. What comes next does not need to be imagined, because it has happened before, is happening now: Foreign food staples are flown in as goodwill gestures but have the effect of wiping out local suppliers and producers in the process.

My mother used to call me to interpret dreams. Weeks into 2010, she called to tell me a story that sounded like a dream, about a man who was seen descending from his home, immaculately dressed every morning, into the ruins of Port-au-Prince. He did this for weeks, and the rumor circulated that he’d lost his mind. Maybe it’s his way of coping, I said. My mother continued with the tale of a family member who lived through the earthquake and was encouraged to leave Port-au-Prince for Miami after months of burying the dead. He didn’t stay in the U.S. long. He returned to Port-au-Prince because, he said, everyone there was suffering in the same way and understood what they were experiencing when someone jumped into the street or screamed out in their sleep. It was easier to bear the memories in like company.

At last report, despite $13 billion in aid poured into the country after 2010, there are still 50,000 people sleeping under tents in Port-au-Prince. Many more live with the memory of tremors and falling walls; the memory of a city that looked detonated after 45 seconds of the earth shaking; the memory of the dead, many covered over with debris, others never to be found. As the earth shakes once more, many have still not recovered from those previous losses. Witnessing the second earthquake, from far away, there is an overwhelming sense of disarray, of emptiness. The recollections of 2010 come flooding back.

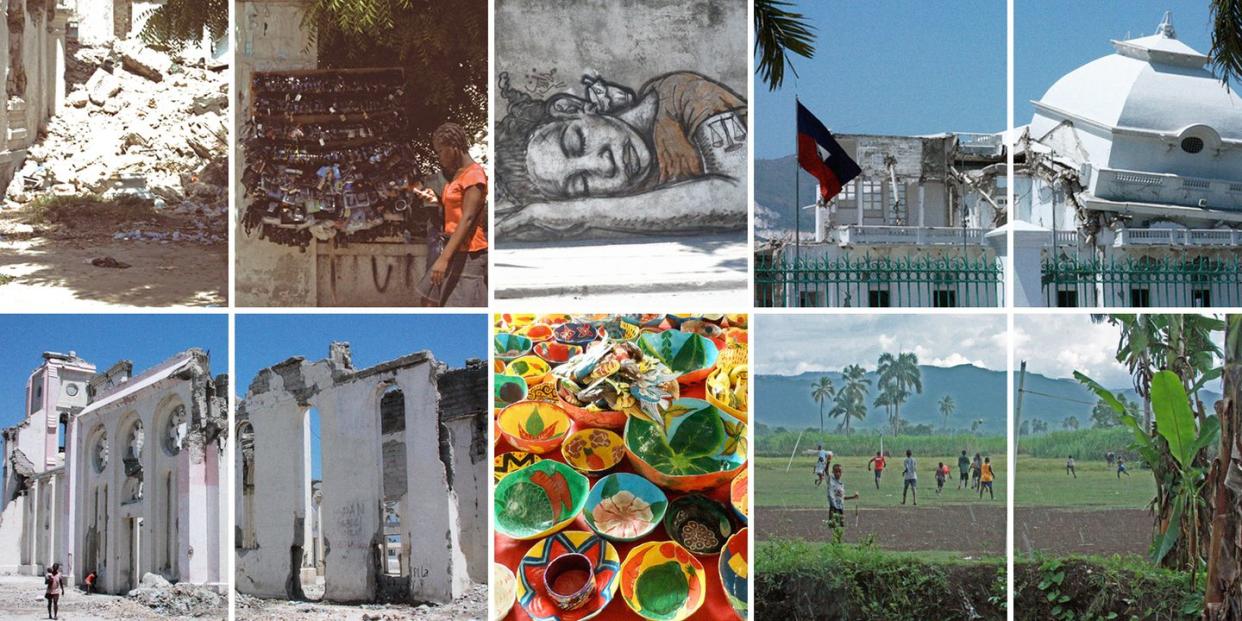

On January 12, 2010, I was about to walk into a classroom when I received several messages. Earlier in the day, we had celebrated my father’s 75th birthday by phone. I turned it off. When I emerged three hours later, I was to find that at 4:53 p.m., as I had been making my way to class, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake had hit Haiti with such force that national landmarks had been decimated. The first images out of Port-au-Prince would be of the fallen walls of the once majestic Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption—also called the Notre-Dame Cathedral—and the dome of the capital building, Haiti’s “White House,” collapsed as if an ornament on a cake. Phone lines were down, or jammed, for days, and it was impossible to know who was dead or alive. Those images confirmed that the unimaginable had happened, after so much else—hurricanes, dictatorship, occupation.

Within weeks, we would learn that all of Haiti’s leading women activists had died that day: Magalie Marcelin, Anne-Marie Coriolan, Myriam Merlet, among them. In a few months, the numbers tallied: 250,000 dead; 300,000 injured, and an equal number of buildings lost; 1.5 million left homeless. In Cincinnati, where I was living at the time, the response to the earthquake was muted. I helped organize a fundraiser, but colleagues and acquaintances soon put the event behind them.

I swam in a blur. A weight swept over me: I could not leave my apartment. When I tried to go for a walk, to get my mind on other things, rays of sun felt like shards of glass against my skin. Survivor’s guilt or something else: It hurt to feel the aliveness of things. A friend invited me to lunch, and I tried to explain the heaviness of accumulating losses. My well-meaning friend responded by saying that the drift of one’s childhood was inevitable, that I needed to put this behind me. I retreated to my apartment. For those of us with ties to Haiti, there was no “putting behind.” The death toll of the 2010 earthquake matched the population of Cincinnati, and I realized that hardly any U.S. resident would be able to even imagine waking up one morning to find their American landscape wiped out, destroyed. Disasters happen elsewhere, never at home, until they do.

Months later, I found out that the dreamlike story my mother had shared was my cousin’s. An engineer by training, he had been hired to assess buildings in the capital because none of his buildings in Port-au-Prince had fallen. Evaluations sometimes entailed crawling into the debris. Since many structures were unstable and anything could happen, he chose not to tell anyone what he was doing until the job was done. When I eventually returned to Haiti, it is this cousin who showed me around. What I saw stunned me, from the makeshift camps crowding open spaces to the rubble piled high as mountains to clear the roads, broken buildings everywhere.

My mother had asked me to check on the house of a friend, close to the Cathedral, in her old neighborhood, a once middle-working class area. We found only rubble, a door propped up against a frame standing without walls. My mother’s friend, a former nun, dreamt of rebuilding. A man came out of nowhere to tell me not to take a picture. I explained that I was asked to take a photograph for the owner. The man was uncertain. He told me he was hired to guard the house. I look back at the rubble. Then, I recognize the turn of the road. I remember the house as it once was, a classic gingerbread. The last time I was there, in my mid-20s, my parents’ friend had a table in the foyer covered in plastic under which she'd placed the photographs of all those whom she loved who were no longer in Haiti. I spotted my mother and father, and myself, as an 8-year-old, someone’s memory. My mother’s friend had survived so many things, but a few years after this, she died, without her home, without the dreams accumulated there.

My cousin took me to see the fallen national landmarks, to see Notre Dame. Once so majestic, its rose walls are now fissured and crumbled. Despite being in ruins, the building was still imposing. We contemplated it in silence. There was nothing to say. As I took pictures, I saw movement from the left side of my camera. A young woman was walking hurriedly towards us with a baby in hand. My cousin tells me that there is a camp set up in front of the Cathedral, that we should go. The moment of turning away is heavy but my cousin is right, there is little we can do. Later, I think about the age of the baby and realize that it was born in the camps.

"The death toll of the 2010 earthquake matched the population of Cincinnati, and I realized that hardly anyone there could imagine waking up one morning to find their American landscape wiped out."

Shortly after Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps sprung up throughout the city, there were widespread reports of sexual violence against women, children, and other vulnerable groups. Women’s watchdog groups warned that girls, especially, would be forced into prostitution, that it was crucial that Haitian women have a seat at decision-making tables. This was not to happen. The Commission of Women for Victims, formed in 2004 by a group of Haitian women survivors of political rape to assist new victims of sexual violence, worked tirelessly after 2010 in an effort to bring perpetrators to justice and to foster healing.

There is a long history of gendered abuse in Haiti. During the Duvalier régime, feminists were intimidated, tortured, raped. Nearly one hundred years before, during the U.S. Occupation of Haiti in the early twentieth century, James Weldon Johnson collected information on behalf of the NAACP, documenting similar abuses by U.S. marines. Before that, as in all plantation systems, rapes of enslaved women by colonials were common. More recently, in 2017, the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti, MINUSTAH, begun in 2004, was brought to an end, in part, because of allegations that UN officers committed gendered crimes in Haiti as far back as 2007, leaving behind fatherless children. While such violence against women and girls by UN soldiers was widespread, there appears to be only one conviction on record, for the rape of a 14-year-old boy. The removal of agricultural tariffs on imported food designed to protect Haiti’s own domestic production of rice and other staples precipitated another gendered crisis. After the earthquake, small producers begged for the opportunity to feed the country. They were denied. The majority of Haiti’s farmers were women.

Today, after the earthquake in August, fears of insecurity were resurrected as tropical storms swept through the region. I've tried to imagine what it must have been like to be that young mother I encountered in 2010, living under a tent at the foot of the broken Cathedral, without clean water for herself and her child, exposed to strangers and the elements. She is one of many who were forced to defer their dreams, or put them aside entirely. Photographs have begun to emerge of earthquake survivors huddled under makeshift dwellings. One is of a small child smiling up at his mother. She can be seen smiling back even though they are both barely covered by tarps that appear left over from the last disaster, offering little protection from whipping rains. Somehow, their smiles betray hope. But is their hope warranted? As in 2010, after this summer’s earthquake, it will be up to locals to set up security patrols and, still, this will not offer enough protection from predation. For these reasons, the Haiti Response Coalition, formed in April 2020 by a wide range of collaborative grassroots organizations to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, is circulating a call for all those operating on the ground in Haiti to establish “new minimum standards” to uphold the dignity, respect, and leadership of Haitians while operating with transparency and inclusivity.

Haitian asylum seekers recently gathered in Del Rio, Texas are indirectly related to the events of this summer but directly related to those of 2010. Most have been making their way from South America to Central America to the U.S. from locations as far as Brazil and Chile, countries, which, after 2010, opened their borders to Haitian immigrants, only to progressively restrict their admission. Despite being initially welcomed, they soon were met with racism and xenophobia. With the spread of Covid-19 leading to the decimation of economies and employment throughout the global South, and the possibility of return foreclosed for both political and natural causes, Haitian migrants have had little choice but to be on the move, fueled by the false hope of a more welcoming administration. However, the images of migrants being greeted by Texas Rangers on horseback using their reins as whips to run down adults and children alike children as they attempted to cross the Rio Grande on foot, holding bags of food above their heads for family members waiting in the migrant camp in Del Rio, are stark, reminiscent of the antebellum South.

I currently live in California, and I have since learned that the protocols my cousin used to assess buildings in 2010 were developed here and adapted for Haiti. Californians fear “the big one.” They joke about it. Golf. Swim. Go to school. Go to restaurants. Get married, divorced, and everything in between. The inevitable is deferred. What if Haiti is just a mirror of who we might all be in the future? If this is so, then what are we prepared to do now so that mothers here and in Haiti can rock their children to sleep without fear of dreaming for a better future?

Myriam J. A. Chancy’s new novel on the 2010 Haiti earthquake, What Storm, What Thunder, is published by Tin House in October.

You Might Also Like