'Nail in the coffin': How Austin-Travis County EMS is grappling with ongoing vacancies

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

WACO — After Erin Ruiz did her first ride-along in an ambulance, she was hooked.

She found her "thing" in San Antonio — working as an emergency medical technician, a role in which she could help people.

Ruiz moved to the Austin area to work as a paramedic nine years ago and later got married and had two kids. But she couldn't afford to live in the city, and her family moved to Waco in March 2022. Not only was it more affordable, but it was also her husband's hometown, and his parents could help with child care.

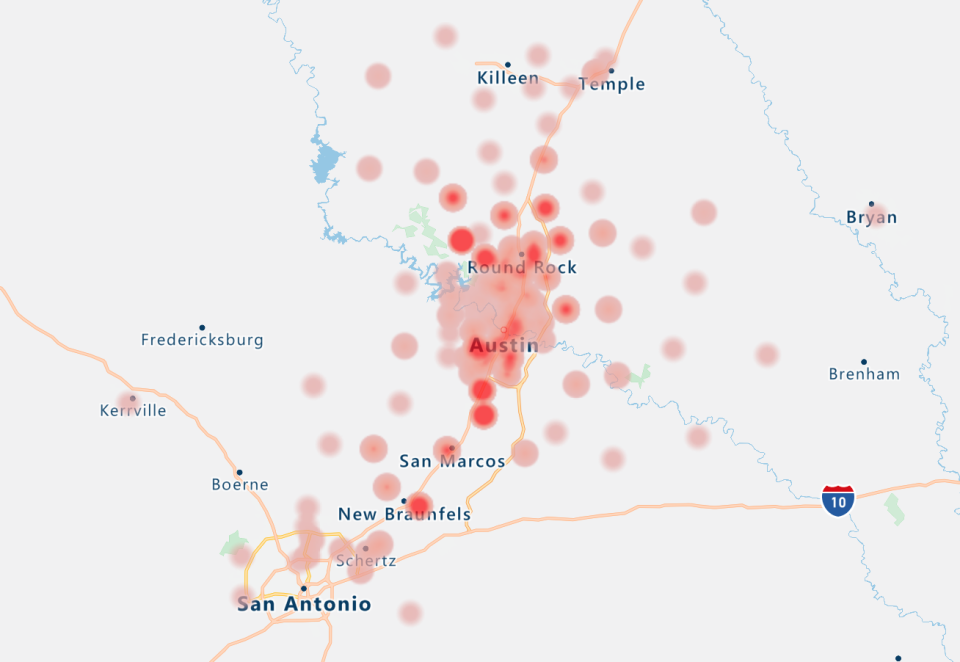

Ruiz wasn't alone. Nearly 78% of the medics working for Austin-Travis County Emergency Medical Services said in a survey last year that they lived elsewhere, in places such as Kyle or Round Rock, because they weren't paid enough to live in Austin, where costs have skyrocketed.

At first, Ruiz made the commute twice a week for her 24-hour EMS shifts. But eventually, "the negatives started to outweigh the positives," she said, so she made the tough decision in June to quit.

"It was painful," Ruiz said this month. "Just a few days ago, I was like, 'I really want to go back,' but I just I can't make it work. If there were a few things that would change, I'd go back in a heartbeat."

For the past few years, EMS has been losing talent, much like other public safety sectors. But while the Austin Police Department is seeing more retirements than resignations, EMS workers are mainly just quitting, according to data provided by both departments.

For Austin-Travis County EMS, this is attributed to multiple issues: burnout, a lack of work-life balance, medics taking higher-paying jobs elsewhere and a poor retirement system. Vacancies in EMS aren't unique to the Austin area; they are common across the state and nation.

For all positions, Austin-Travis County EMS currently has a 17% vacancy rate. Since the fiscal year began last October, the agency has had an average vacancy rate of nearly 20% — and that has also been the average for nearly three years. EMS officials said that when the next cadet class graduates, the department should have about a 12% vacancy rate.

Amid the shortages, the average response time for the highest-priority calls has increased 21% in five years, according to data provided to the American-Statesman.

Austin EMS union seeks better pay, retirement

Selena Xie, president of the Austin EMS Association, the union that represents Austin-Travis County EMS employees, said low pay is the main reason the department continues to lose people. When she spoke with the Statesman in July, she said three people had just quit the week before because they were able to find jobs closer to where they lived for better pay.

The union is negotiating a long-term contract with the city. It has had a one-year contract since October after negotiations on a four-year contract fell through. That happened largely because the city did not offer a package that the union felt was enough to fill the vacancies and improve retention, Xie said.

In Austin, an EMT starts out making $22 an hour. As part of the new contract, the union is proposing that starting wages increase to $24 an hour, with raises based on years of service. The last offer the city made was a $31.3 million pay package, which the union countered with a $33.5 million proposal.

Xie said the union hopes to reach an agreement this month. If not, it will be without a contract in October.

She said 200 medics surveyed spent an average of 40% of their salary on housing. On top of that, the job puts serious mental and physical strain on people.

The union's survey last year asked members to list "how your physical and mental health have been impacted by your work here." The responses had common themes: mental health challenges with an increase in anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder; weight gain or loss; strained interpersonal relationships; insomnia; and feeling unappreciated by the city and administration.

A joint statement from the city's and the association's bargaining teams said they are engaged in "constructive" negotiations and are prioritizing improved compensation and working conditions.

"Both parties recognize the extraordinary challenges and conditions our EMS employees endure during an era of unprecedented public health and public safety crises," the statement said. "We believe the key to meeting these challenges is to increase staffing, and retain and recruit qualified, well-trained emergency medical professionals."

Xie also said EMS doesn’t have a good retirement system compared with other public safety sectors. People working for EMS are on the same retirement plan as regular city employees, so they have to work 30 years and be at least 62 to be eligible for retirement. A firefighter or police officer, however, can work either 25 years or to age 50 and retire.

While action by the state Legislature would be needed to get EMS aligned with firefighters and police, Xie said the city can still make the retirement plan better. That's another proposal for the contract.

Xie said EMS shortages are often overlooked as most conversations about public safety vacancies are focused on police, even though the EMS vacancy rate has been higher, on average, than that of Austin police.

“We've seen the city willing to throw a lot of money into APD’s issues, and we just don't see them as willing to put a little bit of money into EMS issues,” she said. “What we're asking for is (to) make this job attractive to high-quality people who really want to positively influence this community. And right now, we can't do that.”

'We're on a good trajectory'

Butch Oberhoff, president of the Texas EMS Alliance, said EMS agencies were seeing a shortage before the COVID-19 pandemic started, especially in rural areas. The pandemic exacerbated the issue by fueling burnout among workers and sickening caregivers, he said.

Austin-Travis County EMS Chief Robert Luckritz said the vacancy rate peaked at nearly 30% for sworn staff members, but that number has gone down, largely due to the department’s efforts to recruit people from out of state.

EMS in Austin has begun to adopt some changes to help make the work-life balance better, Luckritz said, including changing how it handles mandatory overtime. In the past, if an ambulance couldn't be staffed, people were called in to operate it. Now EMS requires everyone to sign up for one on-call shift a month.

Ambulances are taken out of service if workers are not available to staff them. EMS took ambulances out of service 40 times in July, the lowest monthly number since November, according to data provided by Austin-Travis County EMS.

Austin-Travis County EMS is also trying to fill vacancies by lowering the threshold to be hired as a paramedic. It's now allowing people to come in from its training academy as paramedics if they were already qualified as a paramedic somewhere else. In the past, even those who were paramedics in another city would have to start out as EMTs in Austin. It would take about another year and a half to become a paramedic.

“I truly think we’re on a good trajectory as a department to be able to improve our staffing levels and get us to a point to where we can comfortably staff our ambulances," Luckritz said. "I’m cautiously optimistic that we’re on a good path and there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.”

'Do something a little different'

EMS has seen fewer people quit this year than in 2022. Fifteen people had resigned through June, compared with 31 at the same point last year.

However, Xie said she's concerned that more people are going to quit this year if contract negotiations go sour.

When Ruiz spoke this month about leaving her job, her eyes filled with tears. She didn't want to leave, and she doesn't want others to have to make that decision either.

After nine years of service, Ruiz has a shadow box with her patches and awards to commemorate her time with Austin-Travis County EMS. It's where she met her husband and formed lifelong friendships. Their home in Waco is full of EMS memorabilia, from toy ambulances to the local EMS Association pet calendar to photos displayed throughout the house.

Ruiz was OK with the 24-hour shifts because it meant making a long commute only a couple of days a week. But with a high number of vacancies, she and her peers had to work harder every shift.

"If you got 20 minutes on the recliner, you were lucky," Ruiz said. "That was a bit of the nail in the coffin for me."

To attract more people and retain the current talent — and thus help the medics catch a break — Ruiz said officials must do two things: pay more and make the retirement plan more appealing.

"You're going to get people in the door ... and they're going to move on to other things" after a year or two, Ruiz said. "But if you want the best and the brightest helping your family in that time of need, then you got to do something a little different."

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Why Austin-Travis County EMS has had a 20% vacancy rate for 3 years