‘Nakedly partisan.’ Explaining the lawsuit, objections to Ky. GOP’s redistricting maps

The Kentucky Democratic Party, along with Franklin County residents including Rep. Derrick Graham, D-Frankfort, launched their official legal challenge against Republican-drawn House and U.S. Congressional redistricting maps in Franklin Circuit Court on Thursday.

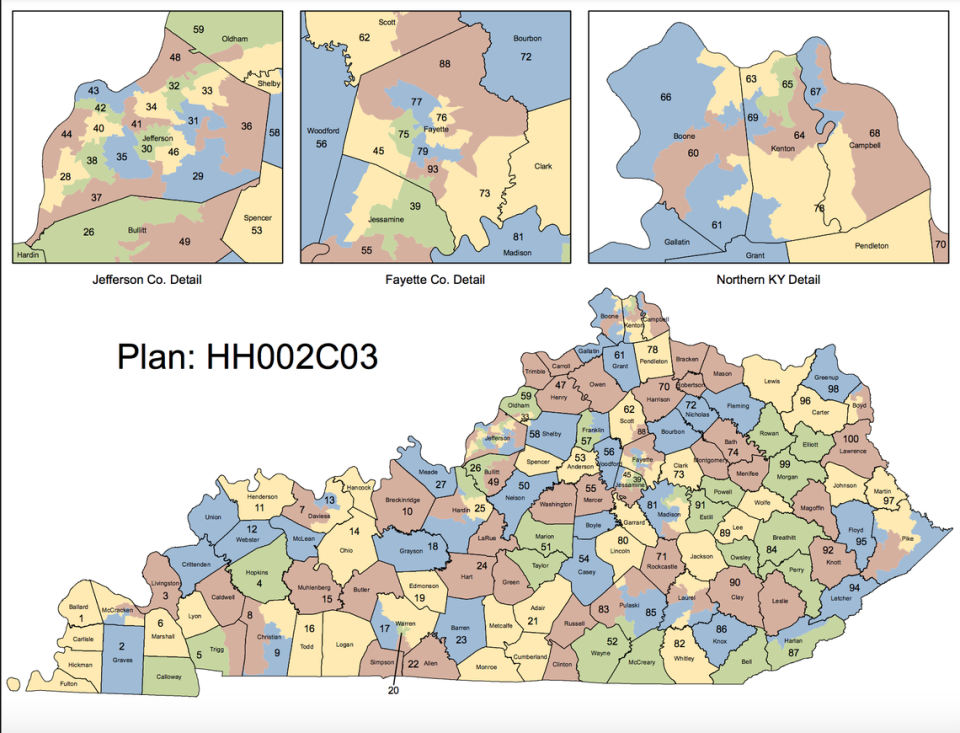

In the suit, Graham v. Adams, the plaintiffs characterize the new maps as unlawful under the Kentucky Constitution and an instance of “extreme partisan gerrymandering” because of how unfair they are to Democrats. Though the only known suit now is in Franklin County, Democrats from virtually every corner of the state found something to complain about in the new maps that will become law after both chambers overrode Gov. Andy Beshear’s vetoes of the new maps.

Beshear called the maps “unconstitutional political gerrymandering” in his veto message, which met vigorous Republican pushback.

The suit is assigned to Franklin Circuit Judge Thomas Wingate, and forwards two main arguments: that the House and Congressional District maps are so gerrymandered in Republicans’ favor that they violate sections of the state constitution including a section that guarantees that “elections shall be equal and free,” and that the counties that are split in the House map are split excessively.

Fayette County Democratic Party Chair Josh Mers said the process can really only be seen one way: Republicans drawing maps in a way meant to further entrench their supermajority grip on both chambers. The GOP already owns a 75-24 majority in the House and a 5-1 majority in among the state’s Congressional Districts.

“To present this plan as anything but to achieve a partisan goal would be dishonest at best,” Mers said.

From the governor’s office, to Fayette County, to Northern Kentucky, to Paducah and elsewhere Democrats across the Commonwealth largely agree with Mers.

Key to understanding the suit is a comparison between maps passed in the early 2010s, the new maps just enacted and Democrats’ proposed House map.

What’s in the suit?

Plaintiffs named in the suit include the Franklin County-based Kentucky Democratic Party, Graham, Jill Robinson, Katima Smith-Willis, Joseph Smith and Mary Lynn Collins.

All the individuals are residents of House District 57, a district not significantly altered in the new proposed map, and U.S. Congressional District 1. The first Congressional District, which stretches from far Western Kentucky all the way to Frankfort, drew criticism across the state and nation for its extension of an oddly-shaped tail that skirted around the Southern edge of the state to snake up into Central Kentucky as far Northeast as Franklin County.

They ask for the new maps to be invalidated and either the old maps to be run on again or for a new map that “complies with all applicable laws.”

It also mentions potentially moving back the filing deadline if necessary. One of the architects of the House map Rep. Jerry Miller, R-Eastwood, has filed a bill that would move back the filing deadline and primary dates by several months, but said that the legislature would only move on the bill if lawsuits like this one drag on into early March.

Franklin County was previously in the 6th District, which is represented by Andy Barr. Barr’s district traditionally features the tightest Congressional race in Kentucky, as Lexington traditionally votes Democrat while Frankfort has often followed suit.

The suit alleges that this new district was drawn for the purpose of “accomplishing two nakedly partisan objectives.” The first is to make the 6th District more solidly Republican by cutting Franklin County out of it and the second is to extend the district to where the suit alleges current 1st District Congressman James Comer lives. Comer and his wife own a home in Frankfort, but he also owns a home and a significant amount of land near his native Tompkinsville, which was previously in the district.

“Thus, the entire populations of three Kentucky counties were used as pawns to achieve the personal and partisan ends of two incumbent Congressman,” the suit reads.

Complaints of gerrymandering

The Democrats lodge similar complaints about gerrymandering with regards to the House map, but there is a question as to whether or not alleged gerrymandering, even if proven, is against the rules. In 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that such gerrymandering can’t be dealt with by federal courts.

The Freedom to Vote Act, which included provisions meant to limit gerrymandering, appears unlikely to make it out of the U.S. Senate because a majority of that chamber does not want to change Senate filibuster rules.

In the week that Republicans took to push through the maps after they were unveiled to the public, they emphasized the thorough vetting process the maps underwent through the lens of the state constitution and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Republican members who lodged successful challenges against earlier maps both as an attorney and plaintiff stressed that the new maps were by the book.

For any judge to rule against the maps on the grounds of gerrymandering, however, it appears they’d have to adopt a new interpretation of the state constitution. In the lawsuit it’s argued that “extreme partisan gerrymandering” means that citizens’ have had their right to “free and equal” elections violated and that sections of the constitution requiring that every Kentuckian’s vote carries the same power are also violated.

There is some precedent to such an interpretation in other states. The lawsuit notes that Pennsylvania’s supreme court sided with that state’s League of Women Voters branch against allegedly gerrymandered maps; similar successes have taken place in North Carolina and Ohio, the lawsuit notes.

“[A]n election corrupted by extensive, sophisticated gerrymandering and partisan dilution of votes is not ‘free and equal,’” the majority opinion read.

The suit relies heavily on the presentation of House Bill 191, the Democrats’ proposed alternative to House Bill 2, as a foil. It also cites data from the Campaign Legal Center to back up its argument that the map is excessively gerrymandered.

The Campaign Legal Center (CLC), a nonprofit election watchdog founded by a former Republican head of the Federal Election Commission that has recently chafed with Republican campaign finance initiatives, concluded that only 17 Kentucky House Districts in the new map were either solidly Democratic or leaned that way.

The analysis was conducted by comparing likely election outcomes under the new maps to revealed voter preferences using recent statewide election results. The Republican dominance under the new maps would far outpace their narrower, but still strong, edge in statewide elections.

Splitting up counties

The other primary argument behind the suit is that 23 counties – which both Democrats and Republicans agree is the minimum number of splittable counties – were split 80 times in the Republican House plan. In the Democrats’ House Bill 191, 23 counties are split only 60 times. The suit argues this violates provisions in the Kentucky Constitution against excessive and unnecessary splitting of counties.

13 of the counties split by House Bill 2 were split more than they needed to be, the suit claims.

The CLC’s analysis concludes that Democratic votes are wasted at a much higher rate than they would be under a fair House map. Analysis of the U.S. Congressional District map, as well as the Senate map, also indicates a tilt in Republicans’ favor but not as severe.

The lawsuit also argues that the maps constitute a Republican exercise of ““[a]bsolute and arbitrary power” over the lives of Kentuckians as well as a violation of the state’s freedom of speech clause on the grounds of gerrymandering.

Conservative Northern Kentucky attorney Chris Wiest, who previously filed a redistricting lawsuit in 2013, said that there are legitimate political criticisms of the maps but that he didn’t think the maps violated the constitution or applicable laws.

He did question, however, the legality of switching districts on candidates who have already filed to run in a district that they were drawn out of. This could be remedied, Wiest said, by a bill introduced by Rep. Kevin Bratcher, R-Louisville, that specifically allows those funds to be carried over.

Impact in Northern Kentucky

The small group in Franklin County, including elected officials, aren’t the only Democrats railing against the new maps.

In Northern Kentucky, a House district occupied by Democrat Buddy Wheatley, D-Covington, swings from a 13-point Democratic registered majority to 17-point Republican. The new map split Covington, which caused the city’s council to formally appeal the state legislature – to no avail.

When the maps were up for debate on the House floor, Wheatley frequently railed against them. But other Democrats in the county are upset, too. Dave Meyer, Vice President of the Kenton County Democratic Executive Committee, echoed Mers in saying that the objective of the new House map was clear: to dilute the Democratic vote.

Further, he said splitting up Covington does harm to that constituency, which is more progressive than the suburban majority of Northern Kentucky. The new map takes the more urban community of Ludlow, along with chunks of Covington, away from Wheatley’s district and adds much of greater suburban Covington and Edgewood.

“They drew the maps with absolutely no regard or respect for the municipal districts, which actually mean a lot up here,” Meyer said. “We organize ourselves and conceive of ourselves as being from these cities, like Erlanger, as much or more than we do as Kenton Countians. To treat them with disregard like these maps do really damages our ability to organize ourselves up here.”

Republicans in the area, like Kenton County Republican Executive Committee President Shane Noem, beg to differ. More districts means more and better representation, he says.

“Kenton County went from two senators to four and four representatives to six,” Noem said. “Now ten people are walking into the Capitol thinking, ‘What does Kenton County need today?’ Covington especially wins in the new maps as they went from one representative in a hyper-minority to three representatives, two of whom are very influential members of the majority party.”

Fayette County loses ground in GOP plan

Fayette County loses its second Lexington-only Senate district, creating a bright blue inner-Lexington district while the rest of the county is paired with much more Republican-friendly counties. The Campaign Legal Center estimates that the new Senate District 13, containing over 123,000 people, is solidly Democratic. Meanwhile all six other Senate districts are going to vote reliably Republican, the group estimates.

The new House map decreases the total number of Lexington House seats from 10 to 9 and cuts the number of exclusively Fayette County districts from six to five. This comes despite the nearly 27,000 extra residents Fayette County has amassed from 2010 to 2020, according to the U.S. Census.

Mers said that there was “no way to justify” Republican changes to Fayette County. He highlighted Cherlynn Stevenson’s district as particularly gerrymandered. Her new District 88 shifts the portion of Fayette County she represents from the Southeast to the North, and gives her a chunk of Republican-friendly territory in Scott County.

“Under these plans it is very possible that Lexington will be represented by only five House Members and one Senate Member that actually resides in Fayette County,” Mers said. “Adding further insult, the Republicans in Frankfort have decided to take legislative efforts to not only take away the voice of thousands in Fayette County but also further their assault on the women of our Commonwealth with their plans for Cherlynn Stevenson’s district.”

In Richmond, a potential swing district city is carved up three ways and just enough to send a minority Democratic candidate to a rural Eastern Kentucky district.

Martina Jackson initially filed for an 81st District that encompassed the heart of Richmond, which has seen somewhat competitive general election races. Now, she’s running in one that includes a smaller slice of Richmond including her neighborhood and the near-Eastern Kentucky counties of Estill and Powell – both of those places have swung heavily for Republicans in recent statewide elections.

Jackson said that the district she initially filed for is “just across the street” from where she lives.

“I’m literally across the street from my former district,” Jackson said. “That definitely made me feel a certain kind of way.”

Jackson said she is excited to run in the 91st District, having grown up in Appalachia and attended Berea College, but recognizes the additional challenges of running as a Democrat there.

Splitting up cities in Western Kentucky

Western Kentucky cities like Paducah, and to some extent Owensboro, were split, lessening the previous primacy those cities had in their respective districts. Paducah’s core, which used to fit almost entirely in District 3, is now much more pronouncedly split by other districts.

Bowling Green’s core district now includes more suburban areas, as Patti Minter, D-Bowling Green, one of a dwindling number of elected Democrats outside Lexington or Louisville, told the Bowling Green Daily News that the city was unreasonably “cracked.”

Corbin Snardon, a 2020 candidate for the state’s Paducah-centric Third House District, said that the map gerrymandered cities in a way that diluted Democratic votes. His native Paducah’s downtown is now split about evenly, while the previous third district kept it whole.

“It would appear that the majority party wants to ensure that Democratic-leaning cities cannot compete with the present majority party,” Snardon wrote.

Hopkinsville saw its core more markedly split than it was in the previous map – though it was already partitioned off.

“Hopkinsville is one of the most racially diverse cities in Kentucky, so it’s no surprise that the Republican state representative map splits the city right down the middle to continue breaking up our communities of interest. It is not fair or mathematically necessary to divide the center of Hopkinsville, as shown by other proposed maps,” the Christian County Democratic Executive Committee wrote in a statement to the Herald-Leader.

“Republicans drew these lines for their own benefit, behind closed doors, at the expense of the communities they claim to serve.”