His name was Booger Red Privett. Here’s why this cowboy is a legend in Fort Worth rodeo

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Fort Worth has a long love affair with rodeo and fat stock shows, dating back to 1896. We built the Stockyards Coliseum (1908) as a venue for those shows. A lot of bronc busters and bulldoggers have performed, but the biggest name in the early years was Booger Red Privett. His story is Hollywood-ready.

Every few years, a writer rediscovers ol’ Booger Red. Among those who have told his story are folklorist J. Frank Dobie and newspapermen Jerry Flemmons, Mack Williams, Cecil Johnson, and Bill Fairley. So, is there anything new to say about him? Absolutely. There’s more to learn about the man known to his fans as “the King of the Saddle.”

Samuel Thomas Privett Jr. was born in Williamson County, Texas. in 1864. By age 12 he had already been dubbed the “Redheaded Kid Bronc Rider” for his flaming red hair and horsemanship. The following year he got his famous nickname when a homemade firecracker blew up in his face. Another kid commented how “boogered up” his face was, and a nickname was born that would follow him the rest of his life. He was not a pretty sight. His face was badly scarred, his eyebrows and half his nose burned off, he had slits for eyes and was mostly blind in one.

He healed eventually and went on to lead a full life. He took what fate had given him and embraced it. He refused to be a “Phantom of the Opera,” hiding his face in the shadows. One story had him arriving at Fort Worth’s Santa Fe Station in 1916 for a show. He went to leave his grip in the luggage room, telling the agent he’d be back for it and didn’t need a check. “If anybody uglier than ‘Booger Red’ of Tom Green County shows up, give him the grip,” he said. “He’s welcome to it.”

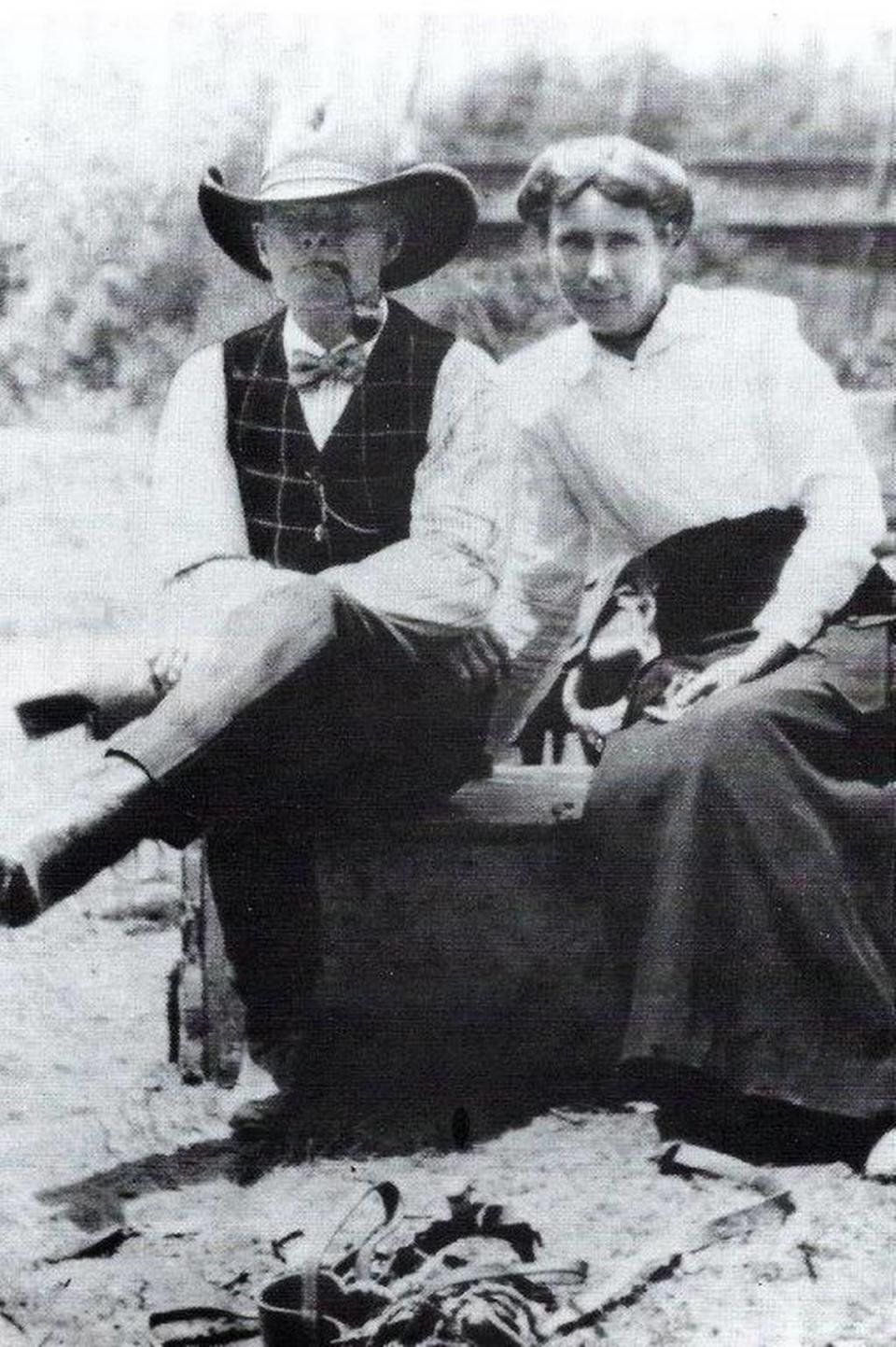

And Booger Red Privett was never lonely. He married Mollie Webb in 1895, and they had six children. It wasn’t just family that loved him. He was a big hit with youngsters at the stock shows. They came up to him, and he told them his story. He could not have been repulsive to so many children.

As a man, he was not much bigger than a good-sized boy, standing about 5 feet 5 inches tall and weighing less than 150 pounds. While years of riding left him hopelessly bowlegged, he was the picture of grace atop a bucking horse. His specialty was breaking horses no one else could ride.

He made money doing it, and it made him a favorite at stock shows and county fairs. Before there were indoor arenas, Privett performed in open fields. Sometimes the horse he was on would take off running. They might be out of sight before he could get the animal under control. He purchased one particularly spirited horse he broke. He named him Montana Gyp, and they were inseparable for the next 23 years.

When Privett decided to go out on his own, he started a family Wild West show with Mollie and the kids performing. He had a standing offer of $500 to anyone who brought him a horse he could not ride. The sheer number of horses he rode in his career is amazing. One source puts the number at 25,000, none of whom ever bucked him off. Mollie Privett was a notable horsewoman herself, earning mention among “Women on the Range” in “Texas Cowboys,” a 1995 book. Eventually, he sold the family show to the 101 Ranch but continued performing with other Wild West shows and circuses. He appeared at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair and performed at the annual Southwestern Exposition and Fat Stock Show in Fort Worth every year from 1918 to 1921.

He finally retired to his ranch in Oklahoma, saying he intended to live out his sunset years at home with Mollie. But he had one more hurrah. Accounts differ about how he came to be at the 1924 Fat Stock Show. Some claim this was to be his last performance before retiring.

Another account says he had retired in 1917, and this was just coming back to the scene of his glory days as a spectator. Either way, he was sitting quietly in the upper stands on March 10 when it happened. A notorious “outlaw horse” had just tossed its rider, and the cry arose for Booger Red, who had been recognized in the stands (not too hard!). He came down to the arena floor and borrowed a hat then mounted the horse. The animal proceeded to pitch every which way but could not unseat him. Privett wore the beast out and brought him to a stand. Then he calmly climbed down. The audience went wild, cheering the “ridinist, ropinist cowpuncher ever raised in the West.” It went down in history as “Booger Red’s Last Ride,” and became the subject of cowboy stories and poems.

Back home, two weeks later he died with his family at his side. The cause of death was Bright’s disease. Booger Red would go down in history as a genuine Western character, plain-spoken and honest to a fault, possessing the kind of smarts that did not come from books. He was a born horseman and a natural performer. Upon his death his contemporaries agreed, “There ain’t never gonna be another Booger Red.” Fifty years after his death, he was inducted into the National Cowboy Museum in Oklahoma City.

His legend in Fort Worth includes the claim that he once broke 83 (or maybe it was 86) horses in a single day. In 1949 the Fort Worth Zoo named a 6-month-old wild hog “Booger Red.” It became a favorite with zoo visitors. But it is the historic Stockyards where Booger Red’s ghost lives on. On the Stockyards Coliseum’s Wall of Fame, there is a photograph of Booger Red atop Montana Gyp, and in 1984 the Stockyards Hotel named its bar and restaurant, Booger Red’s Saloon. There is no record whether Booger Red was a drinker or not - he did smoke a pipe - but he would have felt right at home in the saddle-topped bar stools looking up at the south end of a north-bound longhorn mounted on the wall behind the bar.

Author-historian Richard Selcer is a Fort Worth native and proud graduate of Paschal High and TCU.