'His name is mostly forgotten': Honoring James Rhea, Journal's first Black reporter

In an article dated Oct. 22, 1961, James Rhea wondered whether Rhode Island was any better than the South.

The NAACP had called the state the worst in New England when it came to race relations. Protesters gathered in droves in front of the State House, fighting housing and job discrimination. Providence had one Black doctor and two Black dentists.

Its paper of record had one Black writer: Rhea. Today, it has none.

More: An update on where The Providence Journal is on hiring journalists of diverse backgrounds

Rhea helped earn a Pulitzer for The Journal

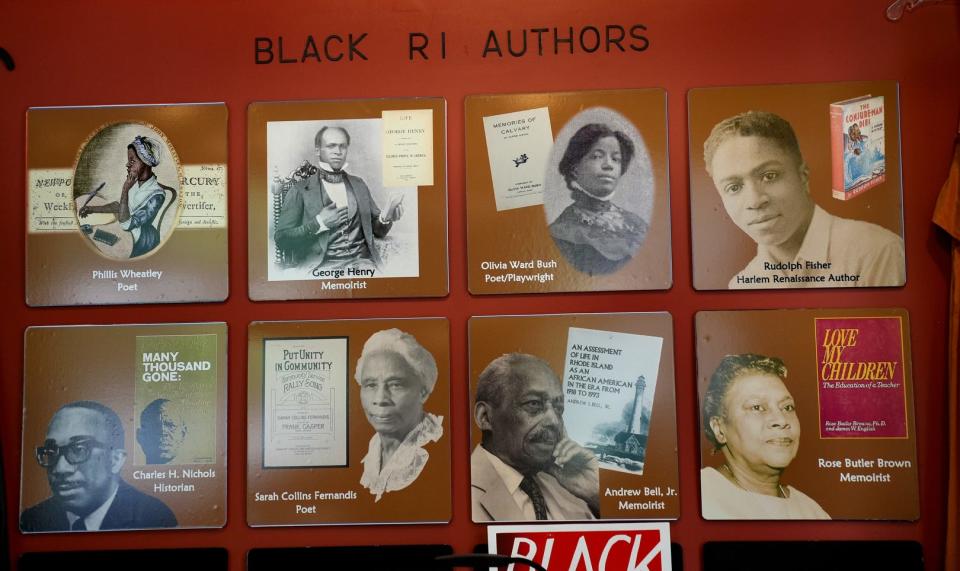

Rhea, who died in 1989, is one of numerous journalists featured in Stages of Freedom’s upcoming exhibit on the Black press, set to open Sept. 21.

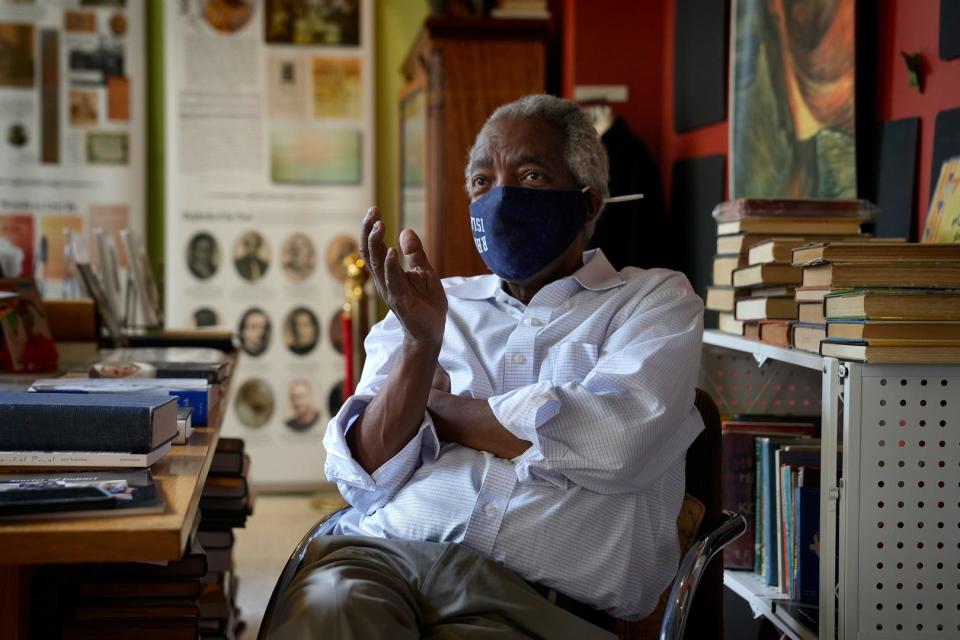

Local civil rights figure Ray Rickman, the museum’s executive director, met Rhea on only one occasion, in 1982, speaking with the reporter for nearly three hours on a bench near Burnside Park.

Amy's Rhode: Amy Russo shares stories from Providence's North Burial Ground

Amy's Rhode: What makes a great clam cake? Amy Russo finds out at the Charlestown Seafood Festival

According to Rickman, Rhea struggled to obtain information from judges and clerks while covering night court, a place notorious for violent stories. Rickman said Rhea was ignored by all but about two reporters at the paper: a Jewish staffer, and a Greek staffer who dined at Rhea’s home on Sundays.

Rhea’s schedule was shifted constantly, but when he complained, he was told he should be thankful for the job, Rickman said.

Rhea retired the following year.

“I tried to talk to two or three of the older editors,” Rickman said. “‘I can’t remember him’ is their defense.”

Rhea was a Pulitzer winner. He and other staff were together responsible for one of the four Pulitzers the paper has earned in its 193-year history, through their coverage of a bank robbery. But as Rickman tells it, to some, Rhea was forgettable.

Amy's Rhode: What's it like to work the boats at WaterFire Providence? Amy Russo was stoked to find out

In fact, in 2019, in a column honoring Rhea’s work, then-Journal executive editor Alan Rosenberg noted that “his name is mostly forgotten.”

The museum’s exhibit is a reminder.

“Every time we start a project … we just sense that there’s more than meets the eye,” said Robb Dimmick, who founded the museum with Rickman.

More: Rhode Island has more Black history than you think. Here's where to see it.

The struggle of Black papers

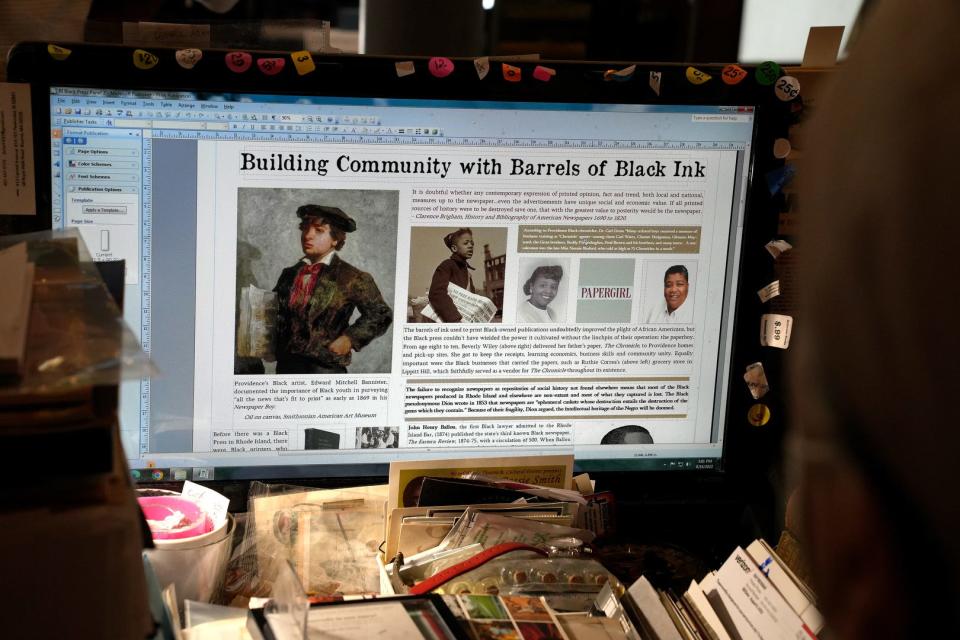

Dimmick spent more than 200 hours researching the state’s Black press, more than doubling the list of Black newspapers he found on Wikipedia. Among those was The Black Warrior, published starting in 1864, which reported solely on the Civil War’s Black 14th Regiment.

Many papers, however, were short-lived. The Republican Sun, launched in 1895, likely ceased publication that same year. The Eastern Review, first published in 1874, became defunct the following year. The Watchman, a religious paper started in 1900, lasted only about a decade.

Amy's Rhode: Amy Russo learns about golf — and grit — on the green at Button Hole

Amy' Rhode: Clams and cannon fire? Amy Russo has a blast at a historical clambake in East Providence

The Chronicle was published from 1937 to 1959, making it one of the most successful Black papers in the state.

Working from inside white publications

Some reporters made their mark within white institutions instead. John Carter Minkins, the only Black reporter to cover the infamous Lizzie Borden trial, was tapped in 1906 for the post of editor-in-chief at the Providence News-Democrat, boasting at the time that he was “the only man of known Negro extraction who has ever been editor-in-chief of a white daily newspaper in this country.”

“He was incredibly fair-complected, could easily have passed, and that may have been his ticket to a lot of his success,” Dimmick said. “But he never denied his African heritage, and worked diligently for the benefit of other African Americans and civil rights.”

Amy's Rhode: Amy Russo tests the waters with a kayak trip on RI's 'wild and scenic' Wood River

Amy's Rhode: What's a BioBlitz? Amy Russo joins volunteers recording abundant life in ordinary places

Save for the Black Star Journal, launched by Brown University students earlier this year, there are no Black papers in Rhode Island.

“It just seems now is the time to tell the story with the absence of a major Black newspaper in Rhode Island,” Dimmick said.

One of the honorees in the exhibit? Longtime Providence Journal photojournalist Kris Craig.

Dimmick performed his trove of research online with endless combinations of search terms to dig up mentions of reporters and newspapers, some of which still have a murky history.

Something of which Rickman is certain?

“Probably without us … all of this would be lost.”

Amy's Rhode: Which famous figures have visited RI's Kingston Village? Amy Russo follows their footsteps

Amy's Rhode: RI's Touro Synagogue, icon of religious liberty, has a lot to teach you during tours

The R.I. African American Press project is funded by the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities and the Herman H. Rose Media Access Fund. Visit Stages of Freedom at 10 Westminster St. in downtown Providence. It is open Wednesday to Friday from 3 to 6 p.m., and Saturday and Sunday from noon to 4 p.m.

Providence Journal staff writer Amy Russo, a transplanted New Yorker, is looking for new ways to experience her adopted state. If you have suggestions for this column, email her at amrusso@providencejournal.com.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Exhibit honors RI's forgotten legacy of Black media