How Nasa’s new Moon spaceship Orion compares with the Apollo spacecraft

In 1969, the three Apollo 11 astronauts — Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin — blasted off from Cape Canaveral Florida atop a massive Saturn V rocket, ensconced in the capsule-shaped Apollo spacecraft. Armstrong and Aldrin would become the first people to walk on the Moon.

Although Nasa hasn’t announced who is going yet, the space agency certainly hopes to send two new astronauts to the lunar surface sometime in 2025, during the Artemis III mission, Artemis being Nasa’s new Moon program. The crew of three will launch in a process not that dissimilar to that of the Apollo astronauts, using a single big rocket, Nasa’s Space Launch System, and flying in their own capsule-shaped spacecraft, Orion.

Nasa will launch a test flight its new Moon rocket and Orion as soon as 29 August, weather allowing.

But despite the obvious geometric similarities, Orion is a very different spacecraft than Apollo, with a different, if overlapping mission. While Apollo aimed solely at the Moon, Nasa expects Orion to fly to the Moon and beyond.

Here’s how the two Nasa spacecraft compare.

What’s the history and development of Apollo versus Orion?

Development of the Apollo spacecraft began in 1961 at North American Aviation, the company that built the spacecraft for Nasa.

The spacecraft was developed specifically for lunar missions and the test flights that led up to them, but early designs were predicated on the idea that the Apollo spacecraft would itself land on the Moon. When Nasa switched to the idea of using a separate lunar module, a second version of the Apollo vehicle that could dock with another spacecraft was produced; that version was used on the Apollo program missions to the Moon, including Apollo 11 in 1969.

The development of the Orion spacecraft predates the Artemis program, which began in 2017. Lockheed Martin began designing Orion for Nasa’s Constellation program in 2004. As part of Constellation, Orion was intended to carry astronauts to the International Space Station, the Moon, and Mars.

President Barack Obama canceled the Constellation program in 2010, but Orion found another life in the Artemis program, while retaining its broad mission — unlike Apollo, Orion is intended to fly to deep space destinations other than the Moon, including Mars.

How do Orion and Apollo compare physically?

The Apollo spacecraft was a truncated cone in shape, a cone with a blunted point. The vehicle weighed around 12,800 pounds without fuel, and stood 11 feet, 5 inches tall and was 12 feet, 10 inches in diameter at the base, which translated to a habitable internal volume of 366 cubic feet — enough to fit three astronauts without a toilet.

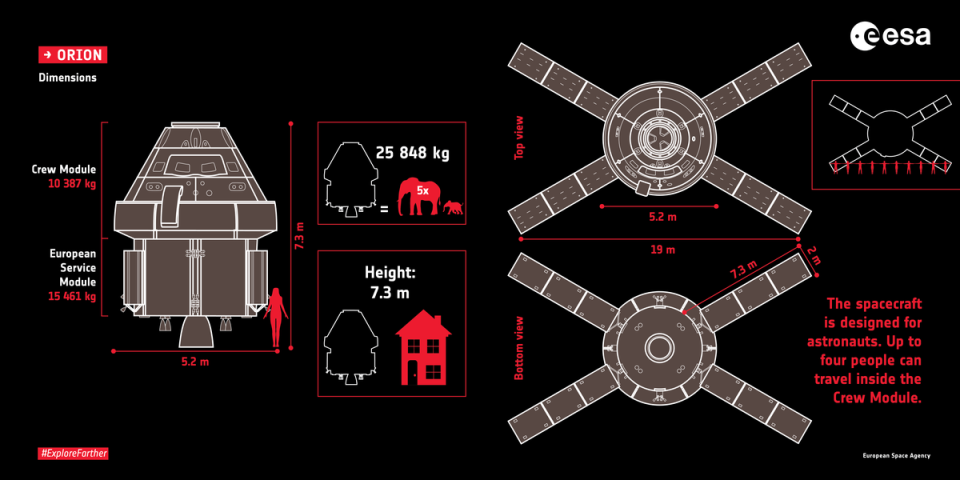

The Orion shares a shape with Apollo, although it is slightly more blunt, and is both heavier and roomier than Apollo. Orion weighs in at 19,000 pounds, and is 10 feet, 10 inches tall and 16 feet, 6 inches in diameter at the base. That translates into a more spacious internal volume of 692 feet — enough to house four to six astronauts with not only a compact toilet, but an exercise machine and a shelter for astronauts during solar radiation events.

Both Apollo and Orion use the same material for their heat shields, Avcoat, a phenolic resin embedded with silica fibers injected into a honeycomb structure. The Orion heat shield is applied in a more sophisticated manner and is designed to take more than did the Apollo shield during high speed reentry in Earth’s atmosphere.

Apollo employed an early form of digital autopilot, but was limited by the computing technology of the 1960s. Rather than the vast array of physical switches and buttons seen in Apollo, the Orion spacecraft utilizes digital controls in a glass cockpit similar to the Boeing 787 Dreamliner, and Nasa has described the Orion computer as 4,000 times more powerful than the computer on Apollo.

Both Apollo and Orion are paired with service modules, cylinders on which the capsule-like spacecraft sit, and which contain the main propulsion and other systems.

The Apollo service module stood almost 25 feet tall including the nozzle of its single AJ10-137 rocket engine and held the fuel and oxidizer for the engine, the primary means of major course correction for Apollo. Electric power was provided by fuel cells utilizing liquid oxygen and liquid in the service module.

The Orion service module is formally known as the European Service Module (ESM), and was built by the European Space Agency. The ESM is around 13 feet tall and utilizes a Space Shuttle era Orbital Maneuvering System Engine as its main propulsion system.

Unlike the Apollo service module, the ESM uses solar panels and batteries for power generation rather than fuel cells. It produces more power than did the Apollo era service module, but also introduces some operational constraints: Nasa’s launch windows for the impending Artemis I test flight of Orion are 29 August, 2 September, and 5 September because on the days in between those dates, the alignment of Earth, Moon and Sun are such that the solar panels would not receive enough light soon enough to power the mission successfully.

How do Apollo and Orion compare in their mission profiles?

Apollo launched atop the massive Saturn V rocket, which was powerful enough to loft the Apollo spacecraft, service module, and lunar lander in one shot. Once in orbit around Earth, the Apollo spacecraft docked with the lunar l

ander, and then headed for the Moon.

After two astronauts descended to the Moon in the lunar lander, leaving the mission pilot aboard the Apollo spacecraft, they would launch back into lunar orbit, dock with the Apollo and then head home.

Orion, launching atop the SLS rocket, will fly a similar path to the Moon for Artemis III, but will not carry its lunar lander along with it. Nasa has contracted SpaceX to build the Human Landing System, a modified version of the SpaceX Starship spacecraft. Orion will dock with the Starship, the latter of which will carry two astronauts to and from the surface of the Moon.

Artemis IV will install the Lunar Gateway, a space station in orbit around the Moon, and future Artemis Missions will see Orion dock with the gateway so astronauts can use it as a way station before descending to the lunar surface aboard Starship or other lunar landing vehicles.

What happened to the Apollo spacecraft?

Although built specifically to fly to the Moon, several Apollo spacecraft were used to fly astronauts to Nasa’s first space station, Skylab in the early 1970s. The last Apollo vehicle flew in 1975 as part of the Apollo-Soyuz project, which saw Nasa astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts dock their spacecraft and shake hands while in orbit.

What’s next for the Orion spacecraft?

While Apollo is literally history, the story is just beginning for Orion.

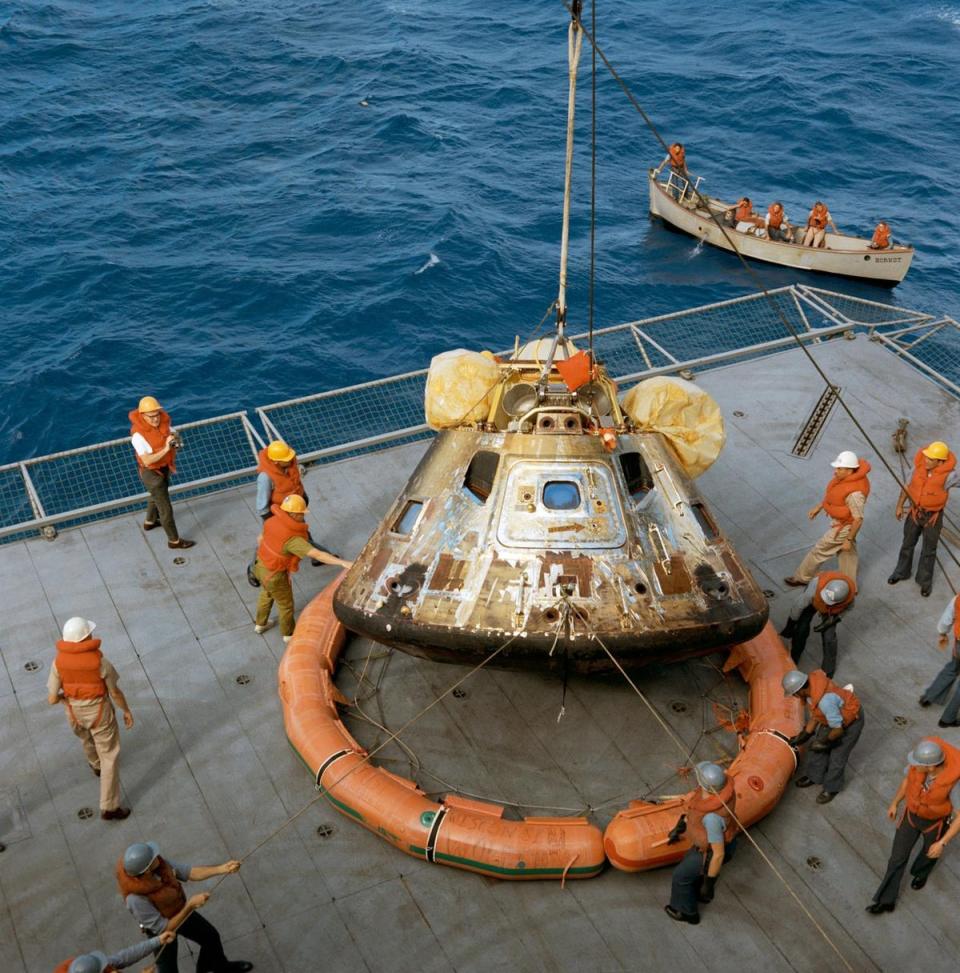

As soon as 29 August, Nasa’s SLS rocket will power Orion into space and toward the Moon for an uncrewed test flight, the Artemis I mission. The mission will see an Orion spacecraft fly to, around, and beyond the Moon before returning to Earth 42 days after launch to test the spacecraft’s heat shield and parachutes, eventually splashing down in the Pacific Ocean.

If all goes well, Nasa plans to conduct a similar lunar flyby with a human crew in 2024, the Artemis II mission. Artemis III, scheduled for 2025, will see humans on the Moon once more.

After that, the future of Orion is up in the air, but Nasa intends to keep flying the spacecraft for further deep space missions. At the very least, Nasa plans to conduct Artemis missions into the early 2030s, building a space station in orbit around the Moon and long term habitations on the lunar surface where astronauts can test technologies and procedures for the space agency’s long term target — Mars.