NASA reaches 'full utilization' of the International Space Station: report

Astronaut time and cargo space are maxed out on NASA's side of the International Space Station.

NASA announced it reached "full utilization" of the International Space Station (ISS) on Jan. 30, which is a milestone, according to SpaceNews. After more than 22 years of continuous occupation of the orbiting complex, crew time and available space for experiments and equipment is at capacity on NASA's side.

"To get at equipment for research, for some of our investigations, the crew has to wade through this stowage and find the right bags," Kirt Costello, NASA ISS chief scientist, told a meeting of the U.S. National Academies last month. "We're currently seeing enhanced amounts of crew time being added to crew activities just to retrieve stowage."

To be sure, NASA manages just a share of ISS activities. Russia has its own space station modules, and half of the United States segment is run by the nonprofit CASIS (Center for the Advancement of Science in Space). Costello said there are options to keep research running smoothly on the agency side.

Related: Wild space 'ferry' concept uses paragliders to return satellites and science to Earth

NASA describes the ISS interior as equal to that of a Boeing 747: that's 32,333 cubic feet (915 cubic meters). That excludes any visiting vehicles, although much of this "habitable" area is devoted to stowage. A portion is NASA space, shared among other station partners, while Russia runs its own side of the space station.

The big activities of the ISS are research and maintenance, and these are limited by available crew time and items on board. A typical half-year space station rotation crew now includes seven people across two spacecraft; that's one Russian Soyuz bearing up to three individuals, and one SpaceX Crew Dragon carrying up to four.

But that situation is an improvement over the immediate post-space shuttle era, when the ISS could no longer rely on two-week shuttle crew missions of seven to supplement ISS crews. For nine years between 2011 and 2020, only the Soyuz was available for astronaut seats until NASA certified SpaceX's Crew Dragon under its commercial crew program. During that decade, ISS crews typically maxed out at six people, or three people per Soyuz spacecraft.

While crew time is at a height these days, the newer problem is cargo — but that should ease somewhat by 2024. "We're waiting on three new vehicles" that will boost cargo shipments to and from the ISS, Costello said at the committee meeting.

Related stories:

— SpaceX Crew-6 astronauts gear up for Feb. 26 launch to space station

— International Space Station: Facts about the orbital laboratory

— See the best photos from the International Space Station of 2022 in this NASA video

Boeing's CST-100 Starliner, the other American commercial crew vehicle that NASA selected to fly to and from the ISS, may be fully certified for astronaut flights this year. That's pending a test flight with two astronauts on board this spring; some of the spacecraft manifest would also include cargo.

Additionally, two robotic cargo vehicle types will be added to the ISS rotation in 2024 or so: Sierra Space's Dream Chaser and Japan's HTV-X, which will replace the nation's older HTV cargo vehicle. (Currently, cargo ships to the space station include SpaceX's Dragon, Northrop Grumman's Cygnus and Russia's Progress.)

NASA is also looking at measures to reduce the amount of stuff flying up and down on cargo ships, such as minimizing brief rotations of bulky research facilities that take up most of a spacecraft's space. In the further future, contributions could be made by companies like Outpost Space, which is considering ferrying cargo to and from the ISS via a paraglider if the technology is ready before the station's expected retirement at the end of 2030.

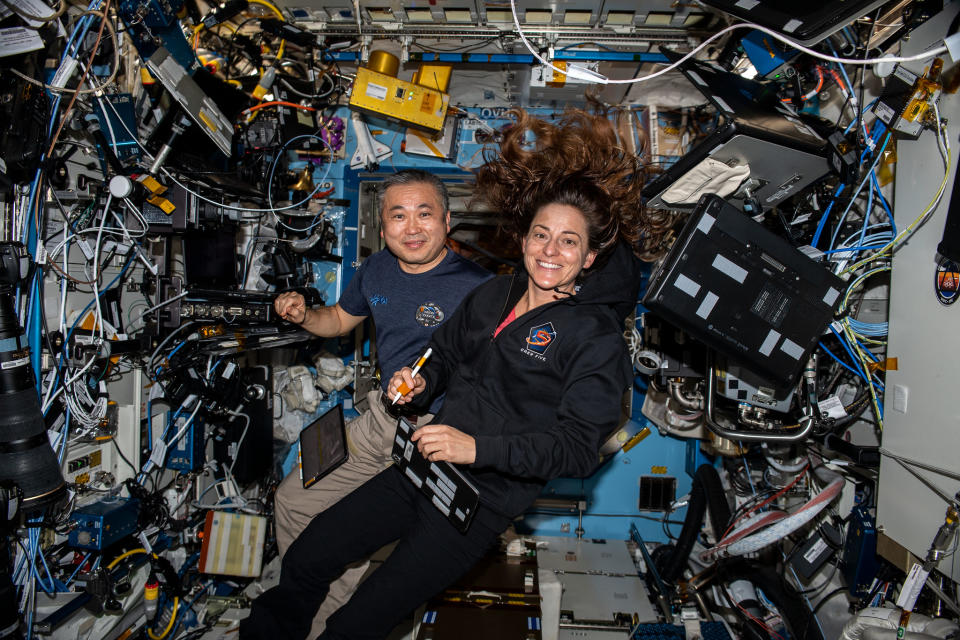

There may be capacity on the CASIS facility side, but that's an unknown right now. NASA is working on a study to see if there are resources to bring to bear in the U.S. National Laboratory on the Destiny module. That said, recent pictures from space show that facility as well looks rather crowded.

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.