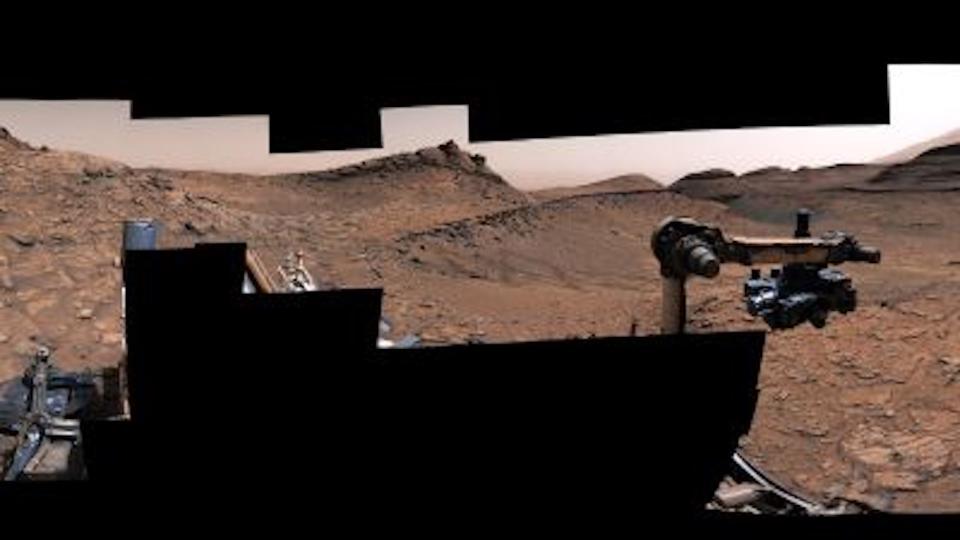

NASA rover snaps photos of ancient 'waves' carved into Mars mountainside

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover has photographed rocks imprinted with tiny ripples from an ancient lake. And these tiny ripples are making waves on Earth, as they are the clearest evidence yet that water once existed on Mars.

The ripple marks were discovered frozen in Martian rock on the slopes of Mount Sharp. Though Curiosity has traversed many rock deposits laid down in ancient lakes, scientists had not seen such vivid marks in the rocks before.

"This is the best evidence of water and waves that we've seen in the entire mission," Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity's project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, said in a statement. "We climbed through thousands of feet of lake deposits and never saw evidence like this – and now we found it in a place we expected to be dry."

Related: Curiosity rover: The ultimate guide

Read more: Curiosity rover: 15 awe-inspiring photos of Mars (gallery)

Since last fall, the rover has been exploring a region of what scientists call "sulfate-bearing" rock. Scientists believe this salt-rich area was deposited when an ancient lake was nearly dry. But the ripples were created on the bottom of a shallow lake as winds created waves on the lake's surface, disturbing the sediments below.

The ripple marks are about 0.5 mile (0.8 kilometer) up Mount Sharp, a mountain made up of a layer cake of rock that records Martian history. The 3-mile-tall (5 km) mountain was once dotted with lakes and streams, making it an intriguing area to search for signs of ancient Martian life, according to the NASA statement.

Curiosity captured a 360-degree panorama of a layer of rock known as the "Marker Band" on the slope of the mountain on Dec. 16, 2022. The rover also attempted to drill into the rocks of this layer, near the rippled features, but the rocks were too hard. Curiosity's drivers plan to look for softer rock in the layer for additional drilling attempts.

RELATED STORIES:

— NASA's Mars rover Curiosity reaches intriguing salty site after treacherous journey

— Mars helicopter Ingenuity's historic 1st flights shed light on Martian dust dynamics

— Signs of Mars life may be too elusive for rovers to detect

The presence of ripples in a supposedly dry area suggests that Mars did not go from wet to dry in a simple, linear manner, the Curiosity researchers said. Near the rippled rocks, researchers also saw rock layers with regular spacing and thickness. These types of layers often occur on Earth during patterns of periodic change.

"Mars' ancient climate had a wonderful complexity to it," Vasavada said, "much like Earth's."

As Curiosity continues to explore the Marker Band, mission scientists hope the rover will get a view of a wind-carved valley known as Gediz Vallis high on Mount Sharp. The valley appears to hold debris from wet landslides and a channel that may have been formed by a river.

Originally published on LiveScience.com.