NASA’s Webb Space Telescope scores big at America’s premier astronomy meeting

It’s not yet clear whether the Seahawks will be in the Super Bowl, but Seattle is in the spotlight this week for the “Super Bowl of Astronomy” — and there’s already an obvious choice for MVP.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope is taking center stage at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society, which has drawn more than 3,400 masked-up registrants to the Seattle Convention Center to share astronomical research and figure out their next moves on the final frontier.

The twice-a-year AAS meetings are often compared to scientific Super Bowls — although the fact that this week’s meeting came on the heels of the soccer world’s biggest event led the National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab to call it the “World Cup of Astronomy and Astrophysics” instead.

This is the professional society’s second post-pandemic, in-person meeting, following up on last June’s AAS 240 meeting in Pasadena, Calif. The $10 billion James Webb Space Telescope was launched a little more than a year ago, but the telescope’s first full-color images and science data weren’t released until July — a month after AAS 240. That makes this week’s gathering something of a coming-out party for JWST.

Jane Rigby, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who serves as JWST’s operations project scientist, said there’s “nothing but good news” about the telescope’s performance. “The science requirements are met or exceeded across the board,” she said during a plenary lecture. “It’s just all so gorgeous.”

It didn’t take long to see fresh evidence: One team of astronomers reported identifying 87 galaxies in JWST’s first deep-field image that appear to date from an early era of the universe, just 200 million to 400 million years after the Big Bang. “Very few people actually expected JWST would find so many candidate galaxies with such a large redshift within just one shot,” study lead author Haojing Yan, an astronomer at the University of Missouri at Columbia, told reporters

The distance measurements for those galaxies still need to be confirmed, but even if only a fraction of the candidates pass muster, “our previously favored picture of galaxy formation in the early universe must be revised,” he said.

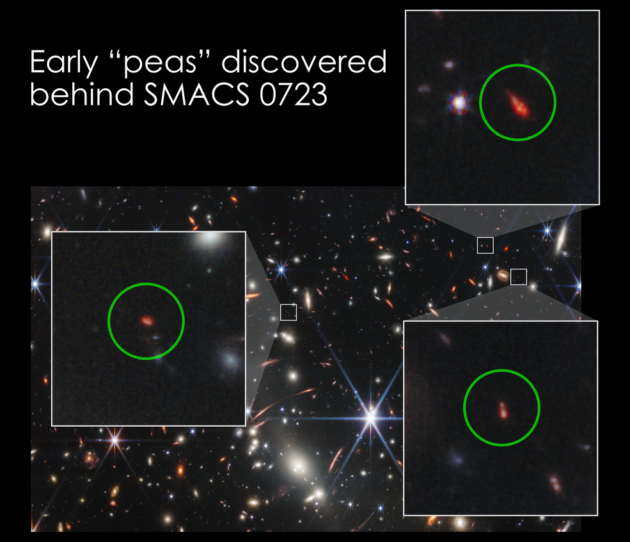

Another team analyzed the same deep-field image and spotted types of galaxies known as “green peas,” which earned their name due to their characteristic shape and color. Green-pea galaxies are hotbeds of star formation, and they’ve previously been detected in our celestial backyard. But the light from JWST’s green peas took 13.1 billion years to reach us.

“With detailed chemical fingerprints of these early galaxies, we see that they include what might be the most primitive galaxy identified so far. At the same time, we can connect these galaxies from the dawn of the universe to similar ones nearby, which we can study in much greater detail,” study lead author James Rhoads, an astrophysicist at Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a news release.

Still more findings from JWST came in hot and heavy today at a news briefing:

Data from JWST confirmed the existence of LHS 475b, a hot rocky planet that’s 99% as wide as Earth. The exoplanet circles a red dwarf star that’s just 41 light-years away in the constellation Octans.

A new infrared view of the dusty disk surrounding a red dwarf star that’s 32 light-years away, AU Mic, provides clues about the composition of the disk.

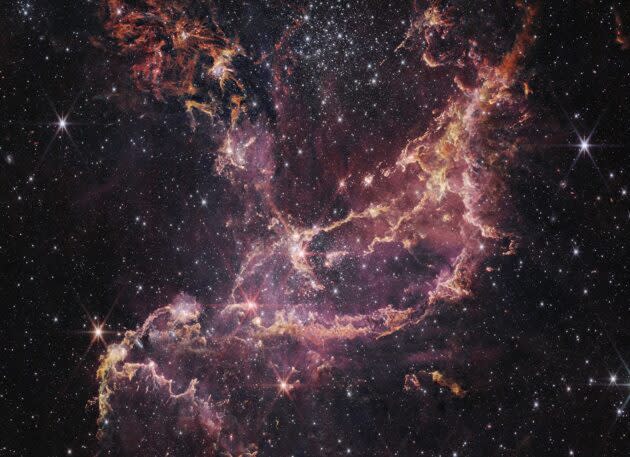

Astronomers released a sparkling new image of NGC 346, a star-forming region in the Small Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf galaxy near our own Milky Way.

Rigby said JWST has “really been behaving itself” at its vantage point a million miles from Earth, but that doesn’t mean its first year of operation has been glitch-free.

The telescope temporarily went into safe mode last month due to a software fault in its attitude control system, and its 21-foot-wide mirror suffered a noticeable hit from a tiny fleck of space debris last May.

To reduce the risk of future micrometeoroid hits, the JWST team will limit observations that have to be made when the mirror is pointing forward toward what’s called the “micrometeoroid avoidance zone.” That safety measure will go into effect starting with the second year of scientific observations, also known as Cycle 2. The deadline for submitting Cycle 2 proposals is Jan. 27.

How many cycles will JWST be able to go through? Thanks to a smoother-than-expected launch, deployment and commissioning phase, the telescope has enough propellant to see it through 20 years of science operations — far more than the five years that were specified as the minimum for success.

“We don’t actually know what will limit the full lifetime of JWST,” Rigby said, “but we anticipate a long and productive life.”

More from GeekWire:

Biden unveils first image from Webb Space Telescope, expanding the space frontier

Feast your eyes on the first course of a celestial smorgasbord from NASA’s Webb Space Telescope

Telescope’s launch makes Christmas merry for space fans, but the ride has just begun

Webb Telescope fires thrusters to settle in at destination, a million miles from Earth