NASCAR's Coke Zero Sugar 400 at Daytona: Five things you might not know

Maybe you're looking to increase your local racing knowledge and or maybe use that knowledge to impress your friends (or maybe bore them to death).

Either way, here are five things you might not have known (or might've forgotten!) about Daytona's annual summertime stock-car race, now known as the Coke Zero Sugar 400 and scheduled to crank to life Saturday night at the "World Center of Speed."

Most eyes on Martin Truex Jr. and Ryan Blaney, but beware the potential first-timers

All the buzz this week involves the looming Cup Series playoffs and which longshot might sneak in and which certified star will be left out (yep, even a recent champion — Truex — might be left on the back porch).

There have been 15 different winners through the first 25 races of the regular season, and if someone makes it 16, and that driver is otherwise eligible (full-time Cup Series, top 30 in season-long points), he rounds out the playoff field.

THROUGH THE GEARS: Kyle Larson wins a race but loses a friend, at least temporarily

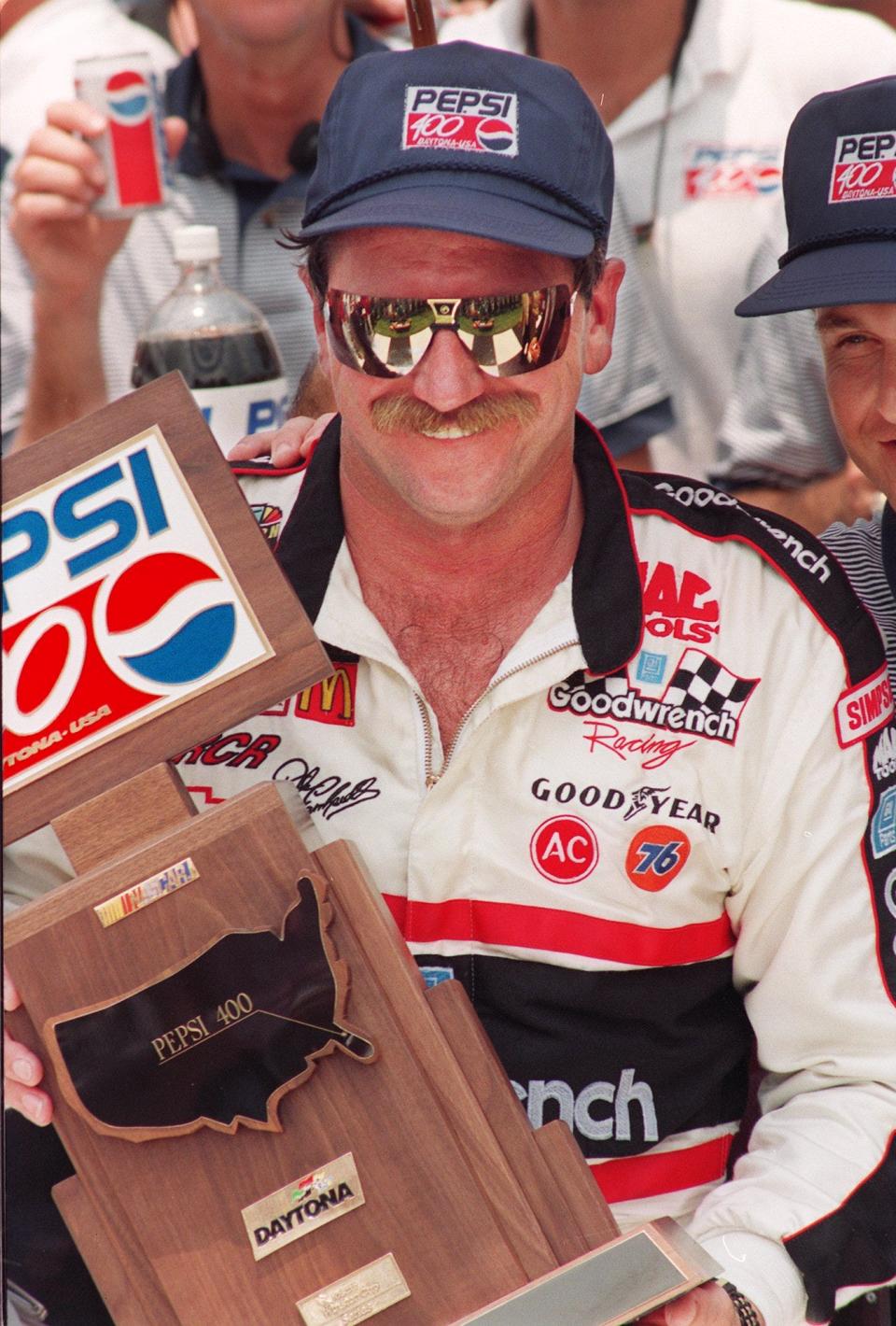

CHASING EARNHARDT: 'Forever tied to my career,' Dale Earnhardt next up for Kevin Harvick on NASCAR's all-time wins list

There are several former Daytona winners currently sitting outside the playoffs who could end up in Victory Lane with new post-season plans — Erik Jones and Aric Almirola come to mind. But Daytona’s summertime race has a history of drivers getting their first-ever Cup Series win.

You need a list? Here you go: A. J. Foyt (1964), Sam McQuagg (1966), Greg Sacks (1985), Jimmy Spencer (1994), John Andrett (1997), Greg Biffle (2003), David Ragan (2011), Aric Almirola (2014), Erik Jones (2018), Justin Haley (2019), and William Byron (2020).

Hmmm, you might be thinking. Who could make the playoffs and earn that first Cup trophy on the same night? How about Todd Gilliland, Harrison Burton or Ty Dillon? At Daytona, the unfamiliar can become familiar up in that lead pack, so don’t say you weren’t given a heads-up.

Corey LaJoie? Sure, he’s very capable in the big-pack drafts, but to make the playoffs you have to be top-30 in points, and LaJoie is 31st and too far out of 30th to matter. That doesn’t mean he wouldn’t enjoy the win, however.

From Firecracker to Pepsi and Coke (the Soda Cracker 400?)

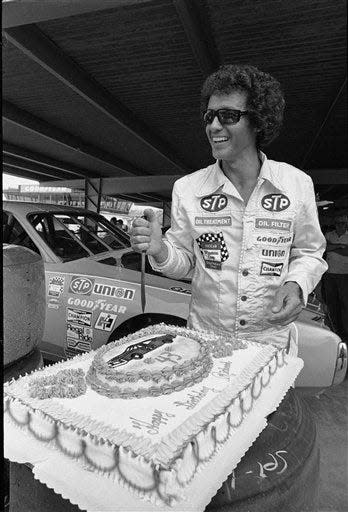

With each passing year, we hear fewer and fewer old-school holdouts who still call this the Firecracker 400, which was the race’s name from its 1959 debut through 1984, when Pepsi upped its Daytona investments and changed the name to Pepsi Firecracker 400.

There was a problem, however, as the Boys in Marketing soon discovered. Pepsi needed its promotional pop, but everyone still called the race by its former name. So four years later, in 1989, the Firecracker was dropped and it was simply the Pepsi 400.

Fun side note: Long-ago Daytona PR man Larry Balewski kept a change jar in the main office during those four years. Any time an employee slipped and used the F-word (Firecracker, not the other one), they had to contribute to the jar.

Nearly two decades later, and nearly five decades after contributing financially to the original building of the mammoth track, Pepsi was replaced by Coca Cola as the official soda of Daytona International Speedway, and the summer race became known as the Coke Zero 400 in 2008.

Four years ago, after many, many marketing surveys and roundtables, the soda’s name was changed to Coke Zero Sugar, and therefore the race’s name was tweaked yet again.

Daytona's Coke Zero Sugar 400 was originally Firecracker 250

OK, let’s go back to the top of the previous item.

Actually, for its first four editions, Daytona’s summertime race was the Firecracker 250, a 100-lapper that didn’t take much longer than an hour and a half.

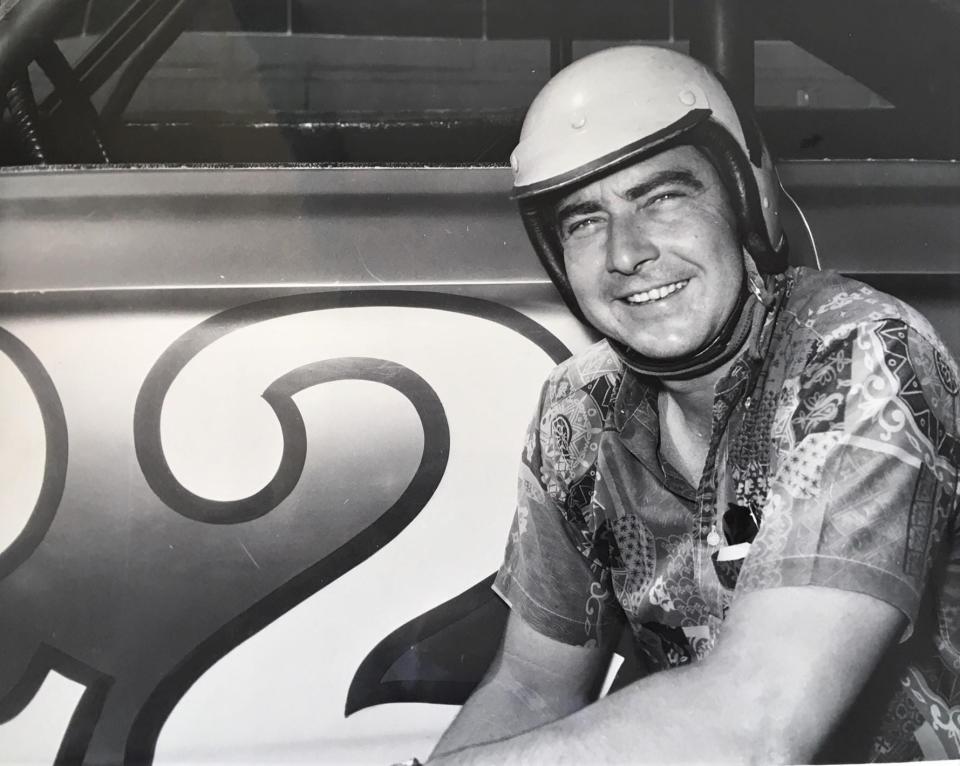

Daytona Beach’s own racing hero, Fireball Roberts, won the first and fourth of those Firecracker 250s, and when it became the Firecracker 400 in 1963, he won that one, too, the season after leaving Smokey Yunick for Holman-Moody.

Originally, Daytona planned for IndyCar, not NASCAR in July

Here’s some trivia you can trot out to impress your friends.

That original Firecracker 250 in 1959 was supposed to be an IndyCar race.

You heard me, the open-wheel, open-cockpit cars made famous in the Indianapolis 500.

One of Big Bill France’s big reasons for building his big track — maybe his biggest reason — was to overtake Indianapolis as the fastest speedway around. The 31-degree banking, compared to the relatively flat Indy, would allow for higher speeds through the turns and therefore rewrite the record books.

So along with his “baby,” the original Daytona 500 in February, 1959, he planned a Fourth of July Indy-style race on the same track. To prepare for it and make sure the cars and new track were compatible, he scheduled a 40-lap (100 miles) IndyCar race for early April.

Most of the big names were entered — A.J. Foyt, Rodger Ward, Tony Bettenhausen, Jim and Dick Rathman, etc. — and they soon learned their sleek (for the day) race cars weren’t fully in tune with the steep banking at those speeds.

The pole speed was 173 mph, compared to 140 for the Daytona 500 six weeks earlier, and 145 for the Indy 500 seven weeks later.

Near the lead and pushing hard on the final lap, “Little George” Amick, a veteran racer from the Pacific Northwest, lost control of his car on the backstretch, barrel-rolled 10 times and died instantly.

His death came six-plus weeks after Marshall Teague died during a solo exhibition run at Daytona in a modified Indy-style car.

Originally spooked and now rightly fearful of the combination of equipment, speed and handling issues, the July plans were scrapped and Big Bill decided to make Daytona a twice-a-year stop for his NASCAR series.

From morning to night, from Fourth of July to late August: Coke Zero Sugar 400 has seen big changes

There have been three major “upheavals” to Daytona’s summer race. Each was met with emotions ranging from dismay to outright anger.

First, beginning in 1988, they moved the race from the Fourth of July to the first Saturday in July. Still, it remained a late-morning start, which often meant a mid-afternoon cool-off across the way at the beach or hotel pool.

A decade later, however, bowing to a modern trend and taking it a big step further, Daytona installed lights around its 2.5-mile tri-oval. They didn’t do it purely for aesthetics or to scare off burglars. Nope, they did it to add night-racin’ to the calendar.

The first big event would be the 1998 July race. As if earning a clap-back from the gods, Daytona Beach’s surrounding areas were beset by wildfires in June of ’98, and things got so bad, the Speedway became a staging ground for emergency crews.

It soon became apparent the Pepsi 400 couldn’t be conducted in a safe and/or comfortable manner for teams and fans.

The race was postponed to October, when it became the 11th of Jeff Gordon’s 13 wins that year.

The most recent change was the biggest: Moving the race from early July, officially dubbed as "Fourth of July Weekend," to late August, where it would become the final race of the regular season and officially set the ensuing playoff field.

What it lost in tradition, it gained in drama. Not that a white-knuckler at Daytona needed much more of that.

This article originally appeared on The Daytona Beach News-Journal: Coke Zero 400: 5 things to know about Daytona's summer NASCAR race