Nashville civil rights veteran Diane Nash to be honored with Presidential Medal of Freedom

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

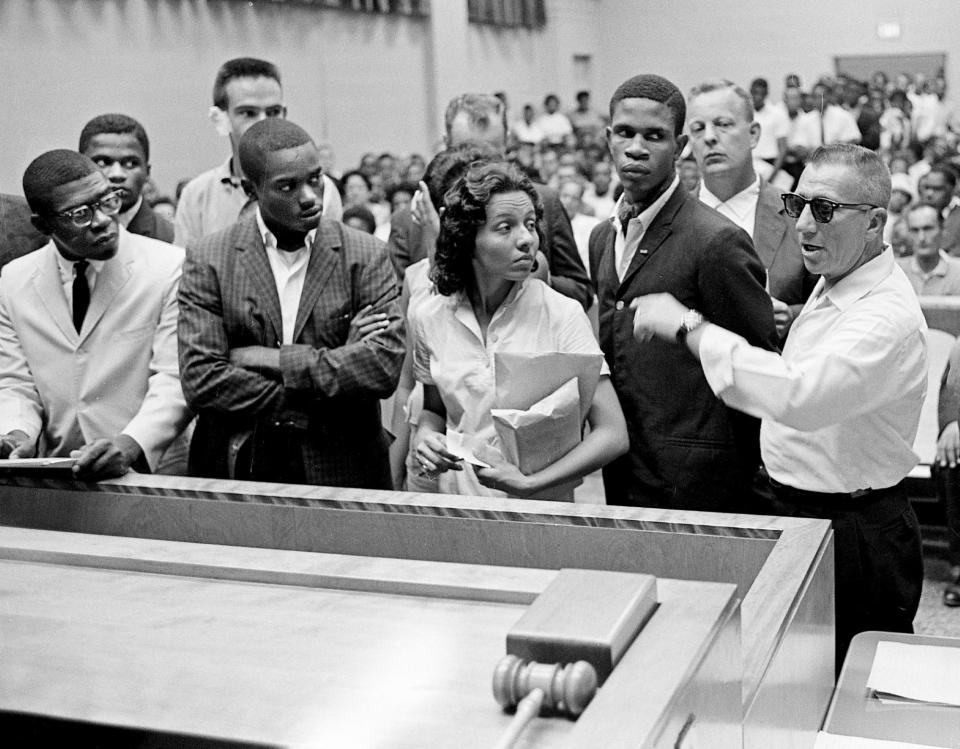

Nashville civil rights veteran Diane Nash, who led sit-ins, coordinated freedom rides and was jailed while pregnant for teaching minors nonviolent protest tactics, will be honored with a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

The White House press office announced that Nash, and 16 others, will receive the prestigious award Thursday.

Famed Alabama civil rights lawyer Fred Gray, who attended school in Nashville and later led some of the most pivotal legal cases of the civil rights movement, will also receive the honor.

The Medal of Freedom is the nation's highest civilian honor reserved for those who have made significant contributions to the "prosperity, values, or security of the United States, world peace, or other significant societal, public or private endeavors," the White House said.

Nash, born in Chicago, moved to Nashville when she transferred to Fisk University in 1959. Incensed by the overt racism she was not accustomed to in Illinois, Nash joined the Rev. James Lawson's nonviolence workshops where they role-played as demonstrators and attackers to ready themselves for all possibilities.

Nash was elected chairperson of the Nashville movement, and she and the Student Central Committee staged sit-ins at lunch counters across the city.

Diane Nash: Historic Metro Courthouse plaza to carry name of civil rights activist Diane Nash

Freedom Rides: Seven women who helped change the nation through Freedom Rides

In 1960, when the home of attorney and civil rights activist Z. Alexander Looby was bombed, Nash wanted to march albeit silent and prayerful. She walked thousands of students down Jefferson Street to the courthouse steps. There, she was met by Mayor Ben West.

Chief among the students' complaints were the segregated lunch counters across the city. West reminded them he'd desegregated the one counter where the city had control — the airport.

When it was Nash's time to confront the mayor, she did so calmly, working toward one important question.

"Do you recommend that the lunch counters be desegregated?" she asked.

West said yes, a pivotal moment for the movement in Nashville. Weeks later, without much attention, Nashville's lunch counters were the first in the South to desegregate.

“We presented southern white racists with a new set of options,” Nash said in 2013. “Kill us or desegregate.”

Last year, the Metro Council approved a bill to rename the Courthouse plaza, the very place she stood while confronting the mayor, as "Diane Nash Plaza."

"I strongly believe that Diane Nash is woefully the most uncelebrated of all the Freedom Riders," At-large Council member Sharon Hurt said in December. "Undoubtedly, she was the most courageous, articulate and determined. She was not the most popular, nor did she seek to be, but she was convicted with her eyes on the prize."

Sixty-two years after Nash confronted West, she's getting a very different response from the current mayor.

This is a proud day for Nashville. Our very own Civil Rights hero Diane Nash will receive the Medal of Freedom from @POTUS. Nash’s courageous leadership in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was instrumental in Nashville’s desegregation movement https://t.co/byjSsaUXh2

— Mayor John Cooper (@JohnCooper4Nash) July 1, 2022

"This is a proud day for Nashville," Mayor John Cooper tweeted. "Nash's courageous leadership in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was instrumental in Nashville's desegregation movement."

Complete Coverage: The civil rights movement in Nashville

A movement emerges in Nashville: With fearless resolve, a nonviolent army waged war on segregation

In the same year she stood on the courthouse steps, Nash helped to found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Then, at just 22 years old, she organized the continuation of the 1961 Freedom Rides from Nashville to Alabama after violent attacks on riders stalled buses traveling from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans.

Nash turned her attention outside of Tennessee. She taught nonviolent protest tactics to youth in Mississippi and was jailed, while six months pregnant, for contributing to the delinquency of minors.

“I believe that if I go to jail now,” she wrote in an open letter, “it may help hasten that day when my child and all children will be free - not only on the day of their birth but for all their lives.”

She was sentenced to 10 days in jail.

Nash supported the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom from her position with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. She was part of the Alabama Project and the Selma Voting Rights Movement and supported the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

U.S. Rep. Jim Cooper tweeted his delight upon learning Nash would be honored with the award.

"There is no more revered name in Nashville than Diane Nash," he said. "She is a hero, a living legend, and I can't think of anyone who deserved this honor more."

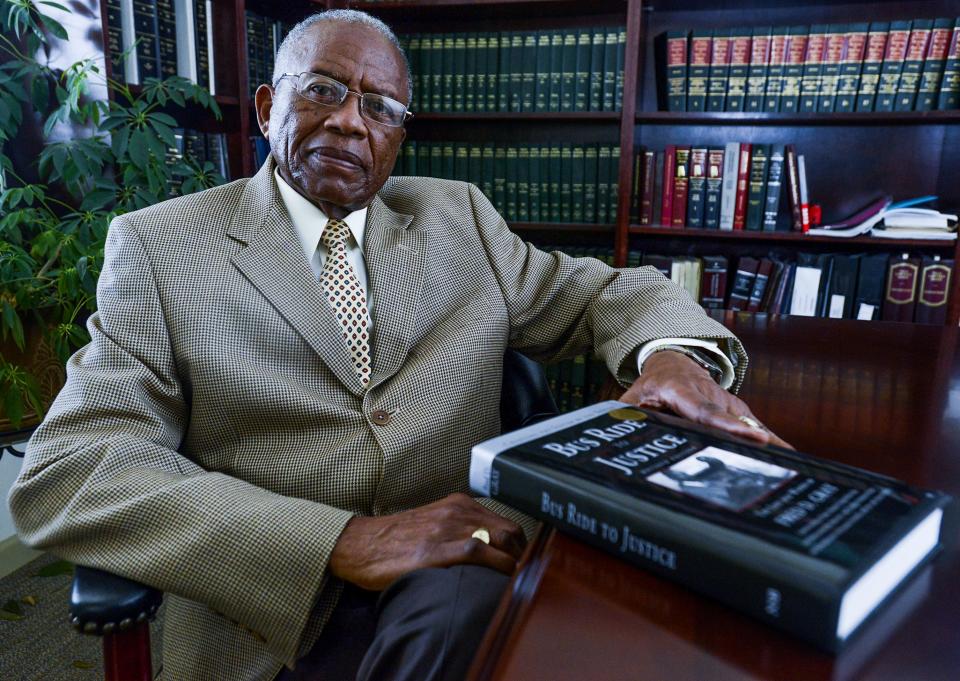

Gray fought high-profile civil rights battles

An Alabama native, Gray spent his formative adolescent years in Nashville.

He attended the Nashville Christian Institute, a now-shuttered prep school affiliated with the Churches of Christ that provided religious education for Black students, who could not attend the similarly affiliated Lipscomb University at the time.

Though he was ordained as a minister through NCI, Gray traveled north to attend law school before returning to Montgomery, Alabama, to set up his own legal practice while ministering at a local church.

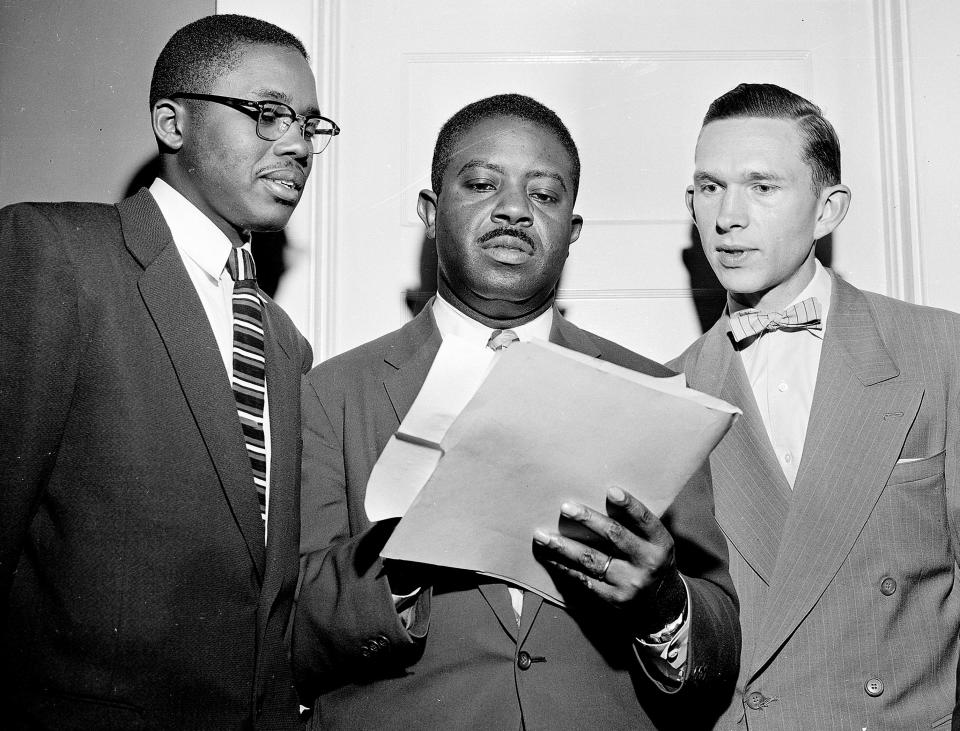

The young lawyer was motivated to "destroy everything segregated I could find," he later wrote, and began taking prominent cases in a city with a highly organized civil rights movement. For years, his legal work helped clear a path for civil rights activists in the South.

More: Fred Gray kept his personal promise, took the protests to the courtroom and won again and again

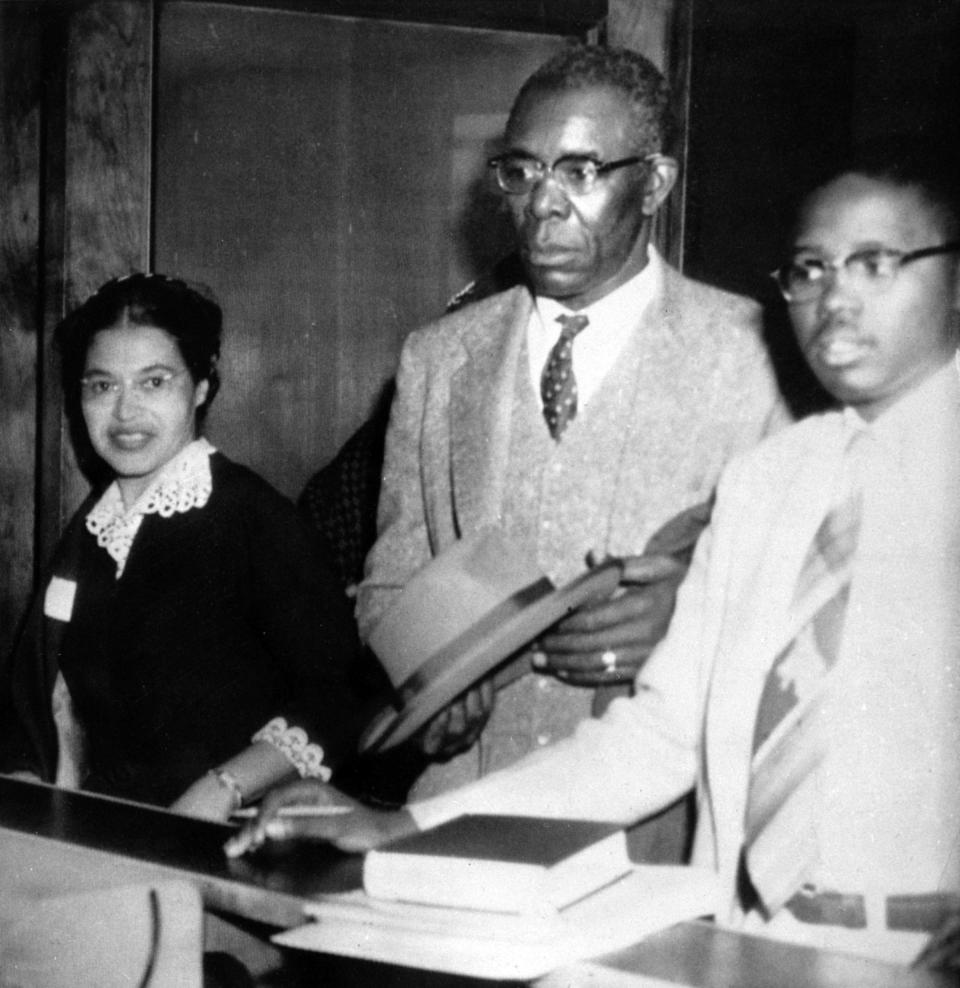

Gray defended Rosa Parks and was one of Martin Luther King Jr.'s first lawyers when the civil rights leader was a Montgomery pastor. Gray later filed the petition in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that found racial segregation on public transportation was unconstitutional, which integrated Montgomery's bus system and ended the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

In the first decade of his legal practice, Gray would go on to play a role in four landmark Supreme Court cases.

He also represented future U.S. Rep. John Lewis, then a Nashville college student, during the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins.

More: 60 years ago, they sat down at Nashville lunch counters — and sparked a movement against segregation

After Lewis and others were badly injured in the Bloody Sunday march in Selma, Gray immediately sued. The case forced Alabama officials to allow another march from Selma to Montgomery, which influenced the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and provide marchers protection from hostile white crowds.

“What I did, I tried to do in a peaceful, loving and non-violent fashion in keeping with the teachings of Jesus,” Lewis said at a Lipscomb event in 2017. Lewis died in 2020. “But when things happened, it was Fred Gray who defended us. He had a great sense of faith that he instilled in all of us. He taught us that when you see something and it’s not right, not fair, not just – to speak up. And sometimes by saying something or speaking up, you’ll get into trouble. But your faith will see you through.”

More: Montgomery may change city law, defy state law to name street for Fred Gray

Gray later became one of the first Black lawmakers elected to the Alabama Legislature since Reconstruction, and he continued filing landmark legal challenges, including suing the U.S. government over the Tuskegee syphilis study.

In 2016, Lipscomb named its Institute for Law, Justice and Society after Gray.

The 91-year-old continues to practice law in Alabama today.

"Attorney Gray epitomizes the enduring legacy of all who sought the law as a means to drive change and push our nation toward its ideals of liberty and justice for all," said Montgomery Mayor Steven Reed in a statement. "For nearly a century, Attorney Gray has been the conscience of the American judicial system, arguing for equity at its highest levels."

Contact Tennessean reporter Kirsten Fiscus at 615-259-8229 or KFiscus@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter @KDFiscus.

Reporter Melissa Brown contributed to this report.

17 to get Presidential Medal of Freedom

The White House said President Joe Biden will present the nation's highest civilian honor to these people this week:

Simone Biles, the most decorated U.S. gymnast in history and an advocate for athletes' mental health, children in foster care and sexual assault victims.

Sister Simone Campbell, a member of the Sister of Social Service and a former executive director of NETWORK, a Catholic social justice organization. She is an advocate for economic justice, overhauling the U.S. immigration system and health care policy.

Julieta Garcia, a former president of the University of Texas at Brownsville and the first Latina to become a college president.

Gabrielle Giffords, a former U.S. House member from Arizona who founded an organization dedicated to ending gun violence after being shot in the head and gravely wounded during a constituent event

Fred Gray, one of the first Black members of the Alabama Legislature after Reconstruction. He was a prominent civil rights attorney who represented Rosa Parks, the NAACP and Martin Luther King Jr.

Steve Jobs, co-founder, chief executive and chair of Apple Inc. He died in 2011.

Father Alexander Karloutsos, assistant to Archbishop Demetrios of America. The White House said Karloutsos has counseled several U.S. presidents.

Khizr Khan, an immigrant from Pakistan whose Army officer son was killed in Iraq. Khan gained national prominence, and became a target of Donald Trump's wrath, after speaking at the 2016 Democratic National Convention.

Sandra Lindsay, the New York nurse who became an advocate for COVID-19 vaccinations after receiving the first dose in the U.S.

John McCain, the late U.S. senator from Arizona who was the Republican presidential nominee in 2008.

Diane Nash, a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee who organized some of the most important 20th century civil rights campaigns and worked with King.

Megan Rapinoe, Olympic gold medalist and two-time Women's World Cup soccer champion. She is a prominent advocate for gender pay equality, racial justice and LGBTQI+ rights.

Alan Simpson, retired U.S. senator from Wyoming who has been a prominent advocate for campaign finance reform, responsible governance and marriage equality.

Richard Trumka, who was president of the 12.5 million-member AFL-CIO for more than a decade at the time of his 2021 death and was a past president of the United Mine Workers.

Wilma Vaught, a brigadier general and one of the most decorated women in U.S. military history, who broke gender barriers as she rose through the ranks. When Vaught retired in 1985, she was one of only seven female generals in the Armed Forces.

Denzel Washington, a double Oscar-winning actor, director and producer and a longtime spokesperson for the Boys & Girls Clubs of America.

Raúl Yzaguirre, civil rights advocate, who was president and CEO of the National Council of La Raza for 30 years. He served as U.S. ambassador to the Dominican Republic.

— Associated Press

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Diane Nash, Fred Gray to receive Presidential Medal of Freedom: