In Nashville, Freedom Rider King Hollands calmly fought racial segregation, memorial set

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Kisha Turner cradles a weathered gray tin cup.

There are a lot of items and spaces that echo her father's spirit — the local flora and fauna he taught his children to respect, the steps of the state capitol where he walked for exercise, and Costco, where he delighted in sampling food with his grandchildren.

But the cup resonates most deeply. It's the kind prisoners clang against jail-cell bars in black-and-white films — now the centerpiece of a coffee table at the family home. The humble dish is surrounded by awards for humanitarian work. It's a keepsake that speaks volumes about Nashville's sometimes-forgotten recent history and about King Hollands, whose legacy is interwoven in the fabric of Music City.

In February 1960, Hollands and other lunch counter sit-in protesters were jailed for demonstrating against ongoing segregation in Nashville. The tin cup was his most important possession during that two-week jail sentence because it held the watery potato soup they mostly served.

He snuck it out of lock-up when he was released.

"He didn't want it to be forgotten — the reason for the Civil Rights Movement," said Turner, one of his three children. "He wanted all generations to know how the doors were opened."

Hollands, 82, died at his Music Row home on Dec. 17 after a short, sudden illness. A memorial is scheduled for Saturday from noon to 2 p.m. at the Fisk Memorial Chapel, 1000 17th Ave. N.

Hollands' name isn't among those typically listed in historical accounts of the Freedom Riders and Nashville Student Movement like its leaders. John Lewis, Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, James Lawson, James Bevel, Jim Zwerg, Z. Alexander Looby, C.T. Vivian and others. But family and friends say his impact will resonate powerfully throughout their lives and beyond.

More: How to celebrate Black History Month in Nashville: Our picks for the culture

He was trained in the disciplined methods of the Nashville Student Movement, which was crucial to ending racial segregation in Nashville and beyond. The group's mission was based on Mahatma Gandhi's nonviolent resistance teachings, and it was deeply aligned with Martin Luther King Jr's Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Throughout his life, Hollands carried those lessons and principles and courageously navigated the front lines of the grassroots movement, starting by integrating Father Ryan High School. He amassed a network of other movement veterans and thought leaders who continue to speak and organize on Nashville's ongoing inequities and growth challenges.

A Fisk alum, Hollands was devoted to the movement throughout his life. Its ideals were infused into his parenting style and his career as a physicist-turned-business-manager, and as an active community member who taught at Nashville's historically Black colleges and universities.

"He believed in the movement and he was very careful and determined about what steps we needed to take," said Rosetta Miller-Perry, publisher of the Tennessee Tribune and a fellow civil rights activist.

"He still felt that Nashville had a long ways to go, which it does."

Impressed by the power of nonviolent protest

As a teenager in 1960, Hollands was charged with loitering and disorderly conduct for sitting at the lunch counter, though it was the crowds around him that acted violently.

Nonviolent, sit-in protesters were burned with cigarettes, spit on, hit and jeered at by onlookers.

He said he was impressed by the power of nonviolent protest during the march to sit at the Woolworths lunch counter. Angry white crowds often backed off when they couldn't provoke protesters to fight.

"After trying to make us fight them, the white crowd in the streets recognized we had a level of discipline, and we wouldn't be provoked by their hate and harassment into fighting them," Hollands told The Tennessean in 2007.

"Finally, they just left us alone."

'Rest in Power': Nashville Civil Rights activist King Hollands dead at 82

In jail, Hollands said he and other protesters were beaten and treated as subhuman. But the attacks only furthered his dedication to the movement.

The lessons he learned 60 years ago during the fight to end segregation in the streets of Nashville carried through his life.

"Daddy was brilliant," Turner said. "He was special. He loved everybody. In order to make progress, someone had to be the bigger person to keep moving forward. He didn't hold grudges."

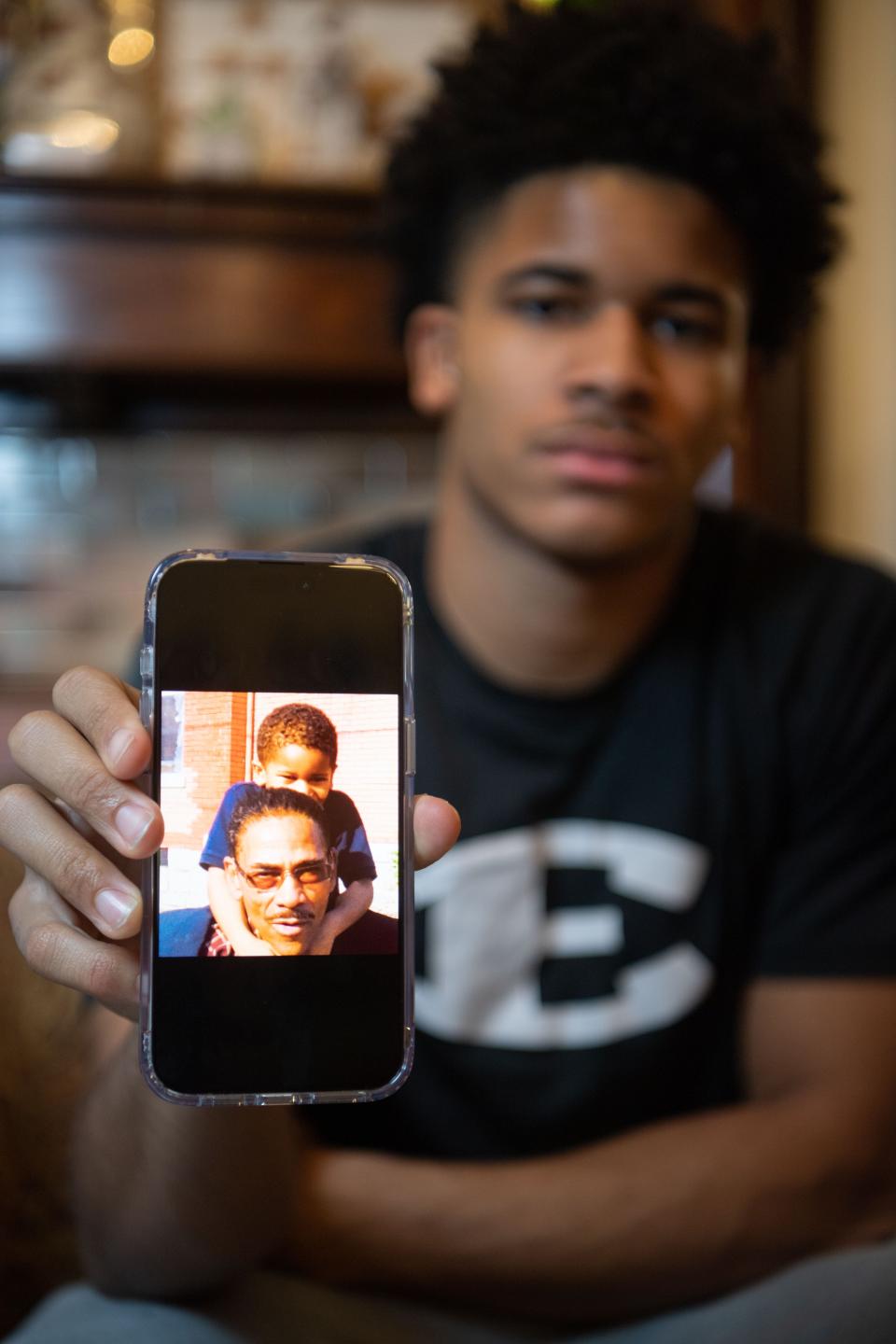

His grandson, Akeem Batey, 15, said Hollands's legacy lives on in his heart.

"I'm usually pretty quiet but seeing what he did makes me want to do the same," Batey said. "(I want) everyone to just be good friends with everyone without thinking they're better than anyone."

'A different type of civil rights leader'

To some fellow Freedom Riders, Hollands was an anomaly. His ready smile and carefree demeanor belied the heavy challenges they fought against.

"Some of us got hot-tempered and angered," Miller-Perry said. "He spoke in a very cool, calm manner. He was a really nice, calm guy. He loved people in the city. He was a different type of civil rights leader to me. I’ve never seen him angry, never seen him lift his voice."

At the tender age of 14, Hollands integrated the first high school in Nashville following the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 ruling that racial segregation was unconstitutional.

He was one of 14 Black students who enrolled at historically all-white Father Ryan High School in September 1954, four months after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision.

At the time, Hollands was allowed to attend the school, but he couldn't participate in sports programs. He faced regular harassment and threats from white students. Once, they threw his books out of a window when a teacher left the room, and they threatened to fight him after class.

But Hollands avoided fights and laid low.

"There were people afraid for their families, their lives, their careers and so forth," Miller-Perry said. "But he was out there, just being a nice guy."

Elite, white New Orleans: Mardi Gras has not freed itself from vestiges of racism

He didn't stay at Father Ryan long. He passed an early-entrance exam to Fisk University at just 15 years old and went on to obtain a physics degree there. After graduation, he became one of the first Black physicists to work at Celanese Corp. in Summit, New Jersey.

"He was unbothered," said his daughter, Konya Williams. "But everyone was special to him."

Through it all, many who met him were struck by his even-tempered, considerate nature.

"He said: 'You can't get frustrated about what's not happening. You have to take small steps that cause big movements,'" Turner said.

'Always willing to help'

His professional career began as a research physicist, but he pivoted to the financial industry and to teach at Tennessee State University and American Baptist College, where he also served as a business manager in the 1990s. He was also a TennCare Information Systems analyst.

In his later years, Hollands focused on his family, friends and community. He taught his children and grandchildren to drive, appreciate nature and pursue higher education.

"He'd take us to Percy Warner Park with our dogs. He'd show us the wildlife," Turner said. "There was no question we could ask that he didn't know the answer to."

Black Nashville: 16 trailblazers, innovators, dreamers that helped shape Music City

He was an active Edgehill neighborhood association leader and nature-lover who advocated to maintain historic African American landmarks, preserve natural areas and prevent encroachment on E.S. Rose Park by Belmont University.

He was a regular helper at Holy Trinity Episcopal Church's weekly soup kitchens.

And he was always happy to lend a hand. He delivered flowers for his daughter's flower shop, freely gave rides to friends and family and loved to cook big family meals.

"He was always on the spot," Williams said. "He would listen to people just to see what they needed. When he heard my designer liked pecan pie, he brought pecan pie every time he came over."

And he was consistent.

At the end of a conversation with him, you could count on Hollands to deliver his favorite catch phrase with a smile:

"How about that?"

Hollands is survived by his lifetime partner and children's mother, Mary Ellen Forrester Hollands; sisters Idrienne Hollands Walker and Cassandra Hollands Harris; children Kisha Marchelle Hollands Turner, Konya Hollands Williams and King Madison Hollands Jr.; grandchildren MarKisha Ellen Hollands-Peoples, Anthony Louis Batey, III, Aaliyah Kishaun Batey Ashton, Deshaun Batey, Kenneth Eugene Ball, Adrian Scott, Akeem Monet Batey, Traci Williams, Trelon Eugene Williams and Danitria Danielle Turner; great-grandchildren Shaun Madison Harris, Anthony Louis Batey IV, Taylor Jeanne Medeiros-Batey, Tristan Eugene Williams, Martin Reid Hodge and Eleanor Ruby Williams.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Memorial set for King Hollands, who participated in Nashville sit-ins